new terrorism - France

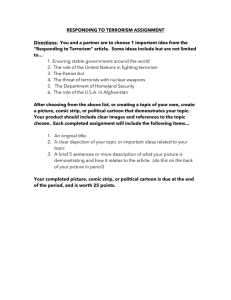

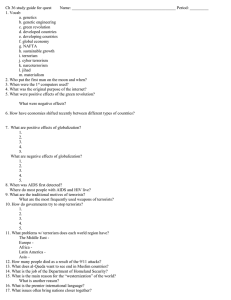

advertisement