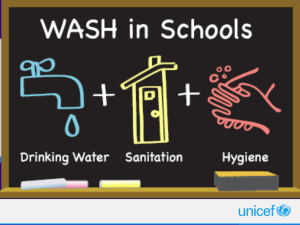

Report - Unicef

advertisement