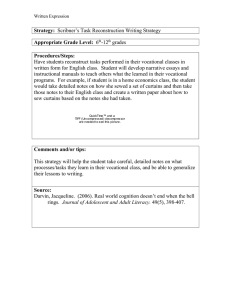

Learning for Job Opportunities: An Assessment of the Vocational

advertisement