Welfare Capitalism and Documentary Photography

advertisement

I would like to thank my fellorvparticipants

in the greaterToronto-areaphoto seminar,

as u'ell as Deborah Martin Kao ar.rclMichelle

Lamunidre,organizersof the symposium 'A

New SocialOrder', held at Harvard

University in April 2007.

Welfare Capitalismand

DocumentaryPhotography:

N.C.R.and the VisualProduction

of a Global Model Factory

ElspethH. Brown

This article examinesthe use of photographv in promoting welfare capitalist

initiativesat the National CashRegisterCompany (N.C.R.) of Dal.ton Ohio in the

early twentieth century. The article arguesthat the company'sfounder, John H.

Patterson,became interested in both industrial betterment schemesand their

photographic documentation as a result of industrial sabotage.In responseto

working-class antipathy to the cash register itsell which was viewed as a

technologyof workplacesurveillance,Pattersonintroduced factory improvement

schemesthat benefited workers at the Dal.ton p1ant.Photographsand lantern

slides documer-rtir-rg

these irnprovementsbecarnecentral to Fatierson'sinternational publicity campaign to render the Dalton plant a global showcasefor

progressivebusinesspractices.The circulation of theseirnagesin a global reform

network allowedthem to function, the article argues,as fetishesofProgressrve-era

utopianisn-r,obscuring the violent details of early twentieth-centuryfactory 1ife.

Like the cash register itself, which became an international commodity in the

1BBOs,the photographs documenting the triumphs of N.C.R.'s industrial

bettermentprogramme gain their value in relationsof exchange,as they circulate

in a global network of Progressive-era

conferences,exhibitions,and educational

endeavoursdesignedto amelioratethe human costsof industrial capitalism.

Keywords:

I'Jational Cash Register, lohn H. Patterson, factory, photography,

Progressive-era, commodity fetishism, cash register, surveillance, sabotage

Photographs are mute documents: their meanings are historically contingent,

shaped by the specific contexts in which they are circulated and read. The

indexical relationship between a photograph's visual message and the 'scene

itself - what Roland Barthes called the image's denotative meaning - anchors

I - R o l r n d B . r r t h e ' '.T h e Ph o to g la p h ic

Message',rn Image/Music/Text,trans.

StephenHeath, New York: Hill and Wang

1 9 7 7 , 1 7 , 2 l ;s e ea lsoElsp e thH. Br o wn , T le

CorporateEye: Photographyand the

Rationslizationof American Comntercial

Culture, 1877 1929,Baltimore:lohns

Hopkins University Press2005, i4 16.

the truth claims of a wide range of images concerned with documentation.l

Historically,

the documentary

photograph's

intimate

world, to actual social conditions, made the medium

claim to the material

a favoured one, not only

for Progressive-era reformers, but also for early twentieth-century

business

progressives, who pushed their fellow capitalists towards a less brutal (if not

paternalist)

approach to labour-management

discussed, the

connotative

photograph's

denotative

meanings: interpretations

relations. But as Barthes also

are always joined by

meanings

that

are shaped socialiy, politically,

and historically. These meanings are structured by the image's style and its

mode of transmission (text and captions, for example), as well as by how the

image is read by diverse audiences constituted through the image's circulation

Historl of Photographl',\rolume 32, Number 2, Summer 2008

ISSN 0308 7298 a 2008 Taylor & Francis

Ekpeth H. Brown

in time and space. In the early twentieth-century US, both reformers and

c apit alis t sr elie d o n th e i n te rp re ti v es l i p p a g eIhal can occur w hen connotati ve

rneanings are taken for denotative meanings - when historically contingent

interpretive frameworks, such as scientific 'objectivity', are taken for material

reality. Early twentieth-century business owners and managers found photography to be an ideal graphic technology in offering their version of workplace

conditions, in what was essentiallya battle of visual rhetoric waged on twin

fronts againstProgressive-erareformers (who sought increasedstate regulation

of private business excesses)and against their more conselwative business

colleagues (who argued for an older interpretation of nineteenth-century

Iaissez-fairepolitical economy).

This essaytakes as a case study the production and global circulation of

photographic documentation by one early twentieth-century US multinational

business:the National Cash RegisterCompany of Dal'ton, Ohio (N.C.R)'2The

images I examine here, drawn from the NCR archivesas well as from Harvard

University's Social Museum Collection, document the company's extensive

welfare capitalist initiatives in the first years of the twentieth century. The

images were made and circulated primarily as a means of publicizing N.C.R.'s

status as a global model factory and functioned, historically, on a number of

levels. I will outline here a few of the registers in which their meanings were

constructed and circulated. As an overall framework for understanding the

cultural functioning of these photographs, I want to suggestthat the images,as

material objects, are fetishesof Progressive-erautopianism. What I mean here

is simply that, in these images, the myriad conflicts that gave rise to both

N.C.R.'s welfare capitalist initiatives and the photographic documentation of

these initiatives, in particular both the workplace surveillanceand the pervasive

industrial sabotagethat accompaniedthe introduction of the cash register into

US economic life, are rendered both invisible and - implicitly - resolveddue to

reformers' intervention. As Marx argued concerning the commodity fetish, in

advanced capitalism the 'fetish' of the commodity works to obscure the

material conditions of its production in favour of the symbolic and economic

value it accrueswhen in circulation; in his terms, the commodity's exchange

value, on the market, renders the good's use value invisible. To fo1low through

with the metaphor of the commodity fetish, the images I shall be discussing

in this essayobscure the violent details of early twentieth-century factory life.

Like the cash register itseli which became an international commodity in the

1880s, the photographs documenting the triumphs of N.C.R.'s industrial

betterment programme gain their value in relations of exchange, as they

circulate in a global network of Progressive-eraconferences,exhibitions, and

educational endeavoursdesiqned to ameliorate the human costs of industrial

2 Although the company was known for

much of its life as 'N.C.R.', in the 1970sthe

name was changedto 'NCR'.

capitalism.

N.C.R. and Early Twentieth-CenturyWelfareCapitalism

National Cash Register,of Dalton, Ohio was an extremely early innovator in a

number of areas of progressive business practices, inciuding 'scientific

salesmanship',visual pedagogy,and welfare capitalism. N.C.R. is still around

today in the form of ATM machines, among other products. In the early

twentieth century, the company's founder, John H. Patterson,began producing

a newly invented machine - the cash register - in a one-room factory with

thirteen employees in 1884; by 1905 he had built a complex of innovative

buildings covering twenty-three acres of floor space, with landscaping by

Boston's Olmstead brothers, and about five thousand employees,both male

and female.sWhile N.C.R.'s work in salesmanshipis fascinating- the company

invented the guaranteedsalesterritory, the salesconvention' the flip chart' and

138

3 Iudith Sealander,Grand Plans:Business

Progressivismand SocialChangein Ohio's

Miami Valley, 1890-1929,Lexington, KY:

University Pressof Kentucky XXXX, 21;

StanleyAllyn, My Half'Century with N.C.R.'

New York: McGraw Hill 1988,28-29.

Welfare Capit alism and D ocumentary Phot ography

4 For further information about N.C.R.'s

importance in the history of sales,see

Walter A. Friedman, Birth of a Salesman:

The Transformation of Selling in America,

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

2004 and his'John H. Pattersonand the

SalesStrategy of the National Cash Register

Company, 1884 to 1922', The Business

History Reriew 72:4 (Winter 1998),552584.

5 - T h i s p a r a g r a p his d r a wn fr o m m y

d i s c u s s i o no f w e l fa r eca p it.r lismin

relationshipto LewisHine's photographyin

The CorporateEye, I),9 148. The key

discussionsof welfare capitalism are Nicki

Mandell, The Corporation as Family: the

Genderingof Corporate Welfare, 1890-19j0,

Chapel Hill, NC: University of North

Carolina Press2002;Andrea Tone, Business

and the Work of Benevolence:

Industrial

Paternalism in ProgressiveAmerica, Ithaca,

NY: Cornell University Press1997;David

Brody, 'The Rise and Decline of Welfare

Capitalism',rn Changeand Continuity in

Twentieth Century America: The 1920s,ed.

|ohn Braemanet al., Columbus: Ohio State

University Press1968,147-78 and Stuart D.

Brandes, American Welfare Capitalism,

1880-1940,Chicago:University of Chicago

Press1976.For a discussionofwelfare

c a p i t a l i . mi n r e l atio n sh ipto co r p o r d r e

public relations,seeRoland Marchand,

Creating the Corporate Soul: The Riseof

Public Relationsand CorporateImagery in

American Big Business,Berkeley, CA:

University of California Press1998 and

Richard Tedlow, Keeping the Corporate

Image: Public Relstions and Business,19001950,Greenwich,CT: JAI Press1979.

6 Sealander,Grand Plans,2l; Carroll T.

Fugitt, 'The Truce between Labour and

Capital', Cassier'sMagazine (September

1 9 0 5 )v o l . 2 8 n o . 5 ,3 4 0 .

7- Image reprinted in Lena Harvey Tracy,

How My Heart Sang: The Story of Pioneer

Industrial Welfare Work, New York: Richard

R. Smith 1950, 112,bottom, with caption

'Mrs. Charles Henrotin Addressesthe

Century Club'.

8 - Industrial Problems, Welfare Work,

NCR: 'FeaturesEducationalto Employees',

ca 1903 SMC 3.2002.3519:ElspethH.

Brown, TLe CorPorateEye: Photographyand

the Rationalizationof American Commercial

Cukure, 1884-1929,Baltimore,MD: fohns

Hopkins University Press,2005.

mandatory salestraining schools, for example - this essayfocuseson welfare

capitalism, since it is the photographic documentation of this work that gave

rise to N.C.R.'s global reputation in the early twentieth century.4

Welfare capitalism is a term used by historians to describethe tremendous

surge of programmes and benefits that progressiveemployers offered European

and American industrial workers in the yearsbefore the rise of the welfare state.

With the major expansion of many mass and specialtyproduction industries in

the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries,the size of factory workforces

grew exponentially, as did the number of often violent confrontations between

labour and capital. In response to high labour turnover rates, industrial

sabotage,unionization efforts, and the growing anonymity of the increasingly

bureaucratized workplace, progressive companies began to offer workplace

reforms in a successfuleffort to reduce labour turnover, increaseproductivity,

and build employee loyalty. These programmes varied widely in scope, but

included company efforts to enable employeesto acquire property and begin

savings accounts; factory and workplace beautification programmes ranging

from landscaping to interior painting; the establishmentof employee athletic

and social clubs; workplace safety programmes; employee lunch programmes

and health care, usually through visiting nurses; pension plans; and employee

representation schemes, known within the labour movement as 'company

untons .N.C.R. was at the forefront of this movement towards what was often

called, at the time, 'industrial betterment' or 'welfare work'. By 1900, around

the time thesephotographs documenting welfare initiatives were in circulation,

N.C.R. offered its male and female employeesthe most comprehensiveset of

employeebenefits in the country. The company's founder and director through

the early 1920s,lohn H. Patterson, summarized the welfare goals as 'physical,

mental, moral, and financial' betterment for workers, instituted through three

strategies:healthful working conditions, pleasant surroundings, and educational opportunities.6 Although I will discusssome of these programmes (and

their photographic documentation) in more detail later, here let me summarize

that the positive publicity accordedthesewelfare capitalist initiatives becameas

important to the company's global reputation as the cash registeritself: indeed,

the two were inextricably linked.

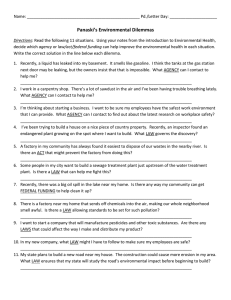

My first illustration includes five black and white photographs

representative of the documentation of N.C.R.'s welfare work during this

period (figurel). Pastedon a sheet of grey poster board with accompanying

text, the photographs detail the educational opportunities for workers,

including a library; motivational proclamations on buildings and bulletin

boards; and speakers organized through the company's various employee

clubs (the top right image describesreformer Mrs. Charles Henrotin, active

in the labour and suffrage movements, as well as the second president of the

generation General Federation of Women's Clubs; she is addressing the

N .C .R . w omen s cl ub i n thi s i mage).7N .C .R . w as al so the fi rst com pany in

the US to start a magazine for employees; as I have discussed elsewhere,

these publications became a central managerial strategy in constructing an

ideology of corporate family togetherness in the increasingly rationalized

workplace.S N.C.R. pioneered a number of conveniences for women

employees, such as a women's dining room; restrooms - literally designed

for rest, a development that was matched in contemporary department store

design; ten-minute recreation breaks in the morning and afternoon, and even

specially designed chairs, at least ten years before post-Taylorite managers

began thinking of what eventually became known, after \MWII, as the field of

ergonomics.

139

EkpethH. Brown

CONIPANY: \\TELFARE

\,VELFARE\{ORK: UNITED STATES.OHIO. DAYTON. NAI.IONAL CAS}I I{F.GTSTER

Figure l. INDUST'I{IAL pROBLEN,IS,

SiIT'CT

GClAtiN

CA

1903.

DL,PARTNIENTS,

OHIO.:

DI\YTON,

PTiNtSIT'ithSClf'

INSTITUI'IONS OF I'HE NATIONAL CASH I{EGTSTERCON'IPANY,

a d h e s i y e l c t t e r so n m o L r nm

t; o u n t: 7 1 r 5 5 .2 cm ( 2 7 1-5/16xl 1 3/,1i n.).H arvardU r]i versi tl 'A rtN Iuseums,FoggA rtN Iuseutn,otd eptl s i t

CarpcnterCeltcr fbr the Visual Arrs, 3.2002.324.Photo: h.nagingDepartment t' Presidentand Fcllou'sof HarvarclCollege

140

WelfareCapitalismand D ocumentaryPhotography

9- Dar.id E. Nye, Inage Workls: Corporate

Identitiesat GeneralElectric,1890 1930,

Cambridge,MA: MIT Press1985.

Although there are other images documenting still other aspects of

N.C.R.'s welfare work in the NCR archives,this placard from Harvard's Social

Museum Collection provides a representativesample of the types of imagesthat

N.C.R. used to publicize its welfare capitalist programmes during the

ProgressiveEra. The photographs bear a staged awkwardnesstypical of both

late nineteenth-century industrial photography and early twentieth-century

public relations imagery.oIn the interior images,the photographer has chosena

long view, seeking to fit as much of the library, auditorium, and slide-room

into the frame as possible:here, qpical of the genre at the time, the spaceof the

model factory is privileged over a visual emphasison the individual subjectivity

of specific figures (through the close-up,for example). The camera,rather than

'catching' the employees at their tasks (a visual rhetoric of pleasurable

spontaneity and company'togetherness'that would mark such imagesafter the

war), here seemsto cement them in place. Whether seatedin their company

chairs, or selectingone of '10,000 lantern slides', these sombre employees

earnestlypursue the uplifting educational diversions of reading, viewing, and

Iistening.

Teachingthroughthe eye:the global circulationof the model

factory image

10- ElspethH. Brown, 'Rationalizing

Consumptior.r:Photographyand

Commercial Illustration, 1913-1919',

Enterpriseand Society1:4 (December2000),

7 t5-738.

1i Dalton History rvebsite,http://

lwn'.daytonhistory.org/magiclantern.htm,

accessed12 April 2007.

Capitalist visuality - in terms of both ways of seeingand in strategiesof visual

representation- emerged as central to N.C.R.'s relationship to employees,its

industrial betterment programmes, its sales strategy, and its international

publicity campaign to render the Dalton plant a global showcase for

progressivebusinesspractices. Patterson was unique among early Progressive

b u s i nessmenfor hi s commi tment to vi sual technol ogi es.\V hile t he ear ly

twentieth century saw advertisersturn to what was known as 'eye appeal', this

emphasis on the visual was unusual in the manufacturing sector.r0Although

Patterson first elaborated his visual pedagogy to his sales staff in the 1880s

through drawings on blackboards and flip-charts, by 1891 he had also

incorporated magic lantern slides to demonstrate aspectsof the cash register

machinerl, to his salesmen.The method worked so well that he created a

Photography Department to produce lantern slides,which were painstakingly

hand-colouredby a staffof sevenwomen.tt By the early 1900s,N.C.R. had over

100,000 stereopticon slides as well as motion picture cameras for the

documentation and display of N.C.R.'s machinery and work innovations.

Thesevisual technologieswere central to Patterson'sstrategy of what he called

'teaching through the eye'.

The stereopticon slides became central to the global delivery of what

becameknown as'The FactoryLecture'.Theserepresentations

of model factory

life circulated domestically and internationally to diverse audiences ranging

from N.C.R. factory employeesat the most local leve1to international world's

fair audiencesat the global. Though in fact the lecturesabout N.C.R. concerned

a number of overlapping topics and titles such as 'The Model Factory', or 'A

New Era in Factory Life', standardizedscripts and images emergedby the early

1900sin the effort to publicize the benefitsof welfare capitalism and the central

role that N.C.R. played in progressiveindustrial betterment schemesin both

Europe and North America. Most of the slideshowsfeatured between 200-230

projected slides, displayed on two parallel screens,in order to compare and

contrast the factory conditions before and after the introduction of betterment

schemes(figure2).

A Newburgh, New York newspaper report describes a tlpical N.C.R.

factory lecture delivered by N.C.R. 'Advance Department' head Arnold

Shanklin in early March 1901. After emphasizingthat'the talk was rn no

141

EkpethH. Brown

N . C " R " Lecture R<xlm,

&n9"

way an advertisement for the machine manufactured by the company', the

lengthy report detailed a tlpical lecture, which began with a brief history of the

company, including its modest founding in 1882 through its explosivegrowth

in the next twenty years.The narrative in this section of the lecture emphasized

businessprogress,the positive attributes of growth, and implicitly, the Horatio

Alger mlth of the rags-to-richesAmerican dream. Shanklin then describedthe

introduction of stereopticon lectures to the factory population and their

families, as a teaching method for the 'best way' to go about their various

duties, to inculcate Patterson's ideas of healthful living (he was a fanatical

follower of many of the era's health fads), and on system in business.Using

imagesdocumenting each aspectof N.C.R. industrial betterment programmes,

Shanklin then escorted the audience on a visual tour of the N.C.R.

kindergarten; the staggered arrival and departure of company streetcars,

allowing women to travel independently of the men; the introduction of

company lunch rooms; the Olmsted landscaping and the successof the boys'

gardening clubs; and the suggestion system and associated prizes. At the

conclusion of the lecture, the pictures of the Patterson brothers filled the

screens;according to the reporter, these images were 'warmly greeted, while

some of the mottoes they have adopted Iand which were also displayed] were

als o gr e e te dw i th a p p l a u s e ' .rThese illustrated factory tours were delivered to multiple audiences,

numbering in the tens of thousands,domesticallyand abroad (figure3). For

example, Shanklin's March 1901 Newburgh lecture was part of a three-month

tour through New England and the south, which included stops in Worcester,

Massachusetts,where he spoke before an audienceof fifteen hundred members

of the Worcester County MechanicsAssociation on 'A New Era in Factory Life';

Rochester,NY; Bridgeport, CT; Scranton, PA; Newark NJ; I(noxville, TN; New

Orleans,LA; Houston and Forth Worth TX, and then back up to Bloomington, IN.

142

Figure 2. N.C.R. LecntreRoom, London,

Eng.,ca I9I2,lantern slide. The N.C.R.

Archive at Da)ton History.

l2 'Twentieth Century Factory', The Daily

/oanral, Nervburgh,NY, 6 March 1901,in

John H. Pattersonscrapbookno. I 14,

pp.45 46, N.C.R. Archir.e,Archive Center,

Dalton Historv. Other newspaperclippings

in this scrapbookreproducealnost

identical descriptionsof Shanklin'sspring

1901tour through New England.

WelfareCapitalismand DocumentaryPhotography

Figure 3. Routing of Factory Lectures,ca

1912,l;rntern slide. The N.C.1l.Archive at

Dayton History.

Rou{ng ol Faelory Leciures

Sp.ing

:'--**

sd

Fdl

*'o*nj"nlt

ot t9I?

. -..

"

'

:',":..,

;

.,

ul\rf[O

't Al't:i

I

13- SJ-rue,v's

lecturesseemedto emphasize

landscapegardening,on n'hich he presented

throughout the west, mid-r'est, and eastern

seaboardin thesevears.He was also

successfulin placing irrticleson larndscaping

and betterment wc:rk in Womdn'sHone

Companion(N{a1,1899) tnd Municipnl

Alfairs. SeeJohn H. Pattersonscrapbookno.

114, N.C.R. Archive, Archive Center,

Da,ytonHistory, as rvell as Edrvin L. Shue,v,

'A Model Facton'Toun', Municipal Affairs,

3 ( M a r c h 1 8 9 9 ) ,1 4 4 l5 l. So m eo f th is

rvork is detailedin Edrvin L. Shue,v,Factorl

Peopleand Their Employers,Nerv York:

Lentilhon & Companr' 1900.

14 AdvtrnceDepartment,'Our Work in

1 9 0 0 ' , ' L - hNeC . R . ( 1 .la n u a r y.

1 9 0 1 ) ,3 0 a n cl

'Welfare', Thc MC.R. (1 lanuar.v190,1),

v o l . 5 n o . 1 , 1 1 . T o g ive a n e xa m p leo f o n e

month, in Septemberof 1903,tl-refactory

received3,075 visitors,from thirty-threc

statesas rvell as smallernumbers of r,isitors

from Canada,Scotland,China, England,

r n d C e r m r n y . : e e' \' isito r . in sg p lsp lr sr ' ,

T l c N . C . R .( 1 N o ve m b e r1 9 0 3 ) ,vo l. 1 6

no.17,679.

1 5 - S e ef o r e x a m p le ' T h eAd va n ce

f ) e p a r t m e n t ' ,T h e NC.R.. ( l Ja n u a r ,v

1900),

v o l . 1 , n o . l , 1 9 a n d T h e M C.R. ( 1 la n u a r v

1 9 0 1 ) v, o l . 1 4 n o . 1 ,3 0 ;fo r Riis' svisit,n ' h e r e

he also lecturedon Nely York renemenr

house reforrn to an audienceof 2000, see

'JacobRiis GivesTrvo Addresses',Ifte

N C . R . ( O c t o b e r19 0 4 ) ,1 3 .

(Shanklin's tour on the utopian possibilities of enlightened managerial

practice was cut short on i May 1901, when N.C.R. was closed due to a

moulders' strike, which I will discuss be1ow.) Shanklin did not invent the

N.C.R. tour; his work as head of what was essentiallythe N.C.R. publicity

department followed that of his predecessorin that position, Edwin L. Shuey.

Shuey,who toured the Midwest and the eastcoastin 1898-1899,gavelectures

to municipal groups, labour organizations,and the generalpublic on topics

ranging from landscapegardening (Minneapolis, luly, 1898) to 'What more

than wagesdoes an employer owe an employee?'(Cleveland,March 1899).13

The circulation of images to domestic audiencesexternal to the N.C.R.

Company was complemented by illustrated lectures in Dayton, designed for

numerous audiences. The 'factory lecture' was an established part of the

internationally known tour of the Dayton manufacturing facilities. In 1900, for

example,about 40,000visitors toured the Dalton factory and its facilities,while

in 1903,43,598visitors arrived; the factory lecture was given both as part of

thesetours, as well as in two hundred other locationsin the US and abroad in

1900.14

Visitors included well-known politicians,businessmen,and reformers,

such as Jacob Riis or members of the US Consul in Australia and Paraguay;

school, community, and civic groups such as the Cincinnati Y.M.C.A., who

sent a party ofeighty-four in 1900;and delegates

from organizationssuch as the

National Associationof Manufacturersand the Daughtersof America.i'These

visits became so numerous that eventually the company standardized them,

offering two tours daily to large groups, whose visit included a stereopticon

(and eventually, motion picture) lecture.

By 1903,the 'factory lecture'becamea simulatedjourney that escortedthe

alldience members from their specific geographical location in England,

Germany, or St. Louis (for example) to the Dai,ton headquarters.By this point,

the company had hired a former employee of the American Mutoscope and

Biograph company, R. K. Bonine, to head the Photography Department; after

his appointment in early 1903,N.C.R. commissionedthe An-rericanMutoscope

and Biograph company to make motion pictures not only of the factory itself,

but also of the sailing of a vesselfrom a harbour, the train journey from New

t43

ElspethH. Brown

York City to Da1'ton;the arrival of visitors into Dalton's Union Station; a tour

of Dal,ton itself; and finally, a tour of the factory and its landscapedenvirons.

E. D. Gibbs, the advertising manager for Europe in 1903, delivered the new

factory lecture to N.C.R. employeesin Dalton, where he used both stereopticon

journey from

slides and motion pictures to sketch the audience's imaginary

then on to

and

York,

Hamburg (where Gibbs would soon be travelling) to New

Da1ton.l6

Motion pictures, as well as the older medium of stereopticon slides,

reachednew audiencesin the era's expositions and worlds' fairs, where N'C'R'

was a prominent exhibitor. At the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland,

Oregon (1903), six N.C.R. lecturersdeliveredthe stereopticonfactory lecture

seven times daily, with extra lectures on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday

evenings;the lectures also simulated the audiences'journey from Portland, the

site of the Exposition, to the N.C.R. factory in Da1'ton.17For the Louisiana

purchase Exposition in 1904, N.C.R. closed its factory for a week in August,

rented train cars from Dal.ton to St. Louis, and subsidizedtrain and admission

feesfor 2,200 employees(including five hundred women) to attend the world's

fair for a week at greatly reduced cost. The fair expo-sition management

declared 3 August 1904 the 'N.C.R. Welfare LeagueDuy'.tt N.C.R. offered the

factory lecture on an hourly basis in the N.C.R. lecture hall at the Palace of

Varied Industries. In addition to the coloured stereopticon lectures, which

featured four hundred slidesprojected to nearly life-sizedscalebefore crowds of

'attentive listeners', the lectures included fifteen hundred feet of film.re These

for

short films featured a variety of N.C.R. activities, including scenestlpical

the new medium such as 'When the Whistle Blows' (views of workers arriving

at the factory); a fire drill by the N.C.R. fire department; female factory workers

piaying tennis and dancing the cotillion; male workers arriving by bicycle; and a

Laseballgame at the company athletic fields.2oAccording to one observer,the

'America'. This

stereopticonlecture concluded with the entire audiencesinging

new colonial

of

celebration

fair's

patrioiic audience ritual complemented the

exhibit,

Philippine

acquisitions, as exemplified in the nearby forty-seven acre

which the same observerargued was.'generallyconcededto be the most unique

and interesting feature of the Fair'."

The N.C.R. factory and industrial betterment representations circulated

outside the united states as well, through both international exhibitions and

through the extensivebusinesstravel of N.C'R. personnel'The N'C'R' had several

exhibitions at the Paris Exposition in 1900 which functioned, as company

president John H. Patterson wrote in an open letter to the employees' as a

(successful)effort to 'inva<leforeign markets'. N.C.R.'s exhibits were awarded

two Grancl Prizes and two gold medals, more than any other US company;

N.C.R. was one of only two US firms to win a 'Grand Prix' for their industrial

betterment work.22 N.C.R.'s exhibition of several hundred photographs and

lantern slides documenting the firm's weifare capitalist programmes was

the

exhibited first in New York, en route to France,and then at severalsites at

a

registers,

Paris Exhibition. In a reception room near the N.C.R. exhibit of cash

large photo album of over one hundred photographs documented the factory

unJ it, surroundings;in the Charity Sectionof the United StatesExhibit' N'C'R'

photographs showed the workers' cottages;Iarge,hand-coloured transparencies

.ho*.ur.d factory education programmes in the US Government Department of

Education section; and in the US Government Horticultural Exhibit, two large

in

photograph albums detailedthe firm's landscapegardeninginitiatives. Finally,

of

industriai

the Social Economy section of the fair, N.c.R.'s lantern slides

betterment programmeswere on display,and it was this exhibition that garnered

one of the firm's two 'Grand Prix'."

r44

16-'Tal k of Mr. Gi bbs',Th eN .C .R .(Marc h

1903),213; 'A ppoi ntmentof Mr. B oni ne' ,

TfueN .C .R .(A pri l 1903),35s .

17- 'The N.C.R. Exhibits at Portland:

Company's Displaysat Lelvisand Clark

Frpo'i ti ort A ttr.rctMuch A tl enti onFactorvLecturelnterestsMan,v',TlreN.C.R.

(Iul v 1903),183.

18- 'Exposition ArrangesN.C.R. Day', The

NlC.R. (.lune 190'l), 20; 'Talks to Girls on

Worl d's Fai r Tri p', The N C .R . (J une1904),

21; 'Woman's CenturY Club at World's

Fatr', Woman's Ifelfore (October 1904),

vol .2 no.3, 83-93; and 'N {.W .W .L.at the

World's Fair', Men's \{elfttre (October

1904),vol . I no.2, 53 60.

19- John Brisben\\ralker, 'World

Instruction in Pictures:How .[ohn H.

Pattersonand GeorgeWestinghouseUse

the Biograph', The N.C.R. (.lanuary1905)'

vol .18 no.1, 14-16,fi rst p ubl i s hedi n The

MagazindsWorld's Fair issue;

Cosmopolitan

for the number of fllm feet, see'Moving

PicturesTaken', The N C R (.luly 190a)'57'

For a fuller discussionof the industrial films

that becamea standardpart of N C.R.'s

Iecturebureau by the late 'teens,see

'Motion PicturesWe Have Made', N.C.R.

Nervs(March 1920), 19.

20 'lvloving PicturesTaken', TfueN.C.R.,

57.

2l- 'Wonan's Century Club at World's

Fair', \,\iontan'sWelJare,91

22-'The P ari sE xposi ti on:The Great

School-Houseof the World, a Letter from

PresidentJ.H. Patterson',TfueN.C.R. (15

N ovemberi 900), vol . 13 n o.22,498 503.

N.C.R.'sgold medalswere arvardedfor their

cash registerdisplay in the Depafiment of

DiversifiedIndustriesand for their

landscapegardeningrvork, displtryed

photographicallyin the Horticultural

Department;the Grand Prix, the highest

honour, was arvardedfor N.C.R.'sdisplayin

the l)epartment of SocialEconomY

concerningindustrial bettermentprograms

at the company, ar.rdthe other was for the

cashregistersdisplayedin the Department

of DiversifiedInclustries.See'Our Paris

H onors', l -heN .C .R .(1 N ov ember 1900)'

(18

vol . 13 no. 21, 481-4931N ew Y orkTi me-s

A ugust 1900),9.

23-'Our Paris Exhibition Display', Tfte

A r.C .R(l. March 1900),v ol . 13 no.5,96-97'

The New York showing was at the hone ot

Miss Helen Gould, of 5th Avenue, and

focusedon the exhibition to be displayedat

the SocialEconomYsectionof the

WelfareCapitalismand DocumentaryPhotography

exhibition; ]osiah Strong and William H.

Tolman, who were organisingthe Social

Economv sectionwith the goal of starting a

SocialMuseum in Nelv York after the close

of the Paris fair, gave talks to an audience

t h a t i n c l u d e dw e ll- kn o wnp r o g r e ssi\e

refomers lane Addams and Mrs. Russell

Sage,as rvellas John H. Pattersonof N.C.R.

See'Exhibition at Miss Gould's', New York

Ilmes clipping, John H. Patterson

scrapbookno. 84, N.C.R. Archive, Archive

Center, Da;.ton History.

24- For more about the US efforts in these

yearsto createa museum ofsocial economy

similar to Paris'sMus6eSociale,seeLeopold

Katscher,'Modern Labour Museums', The

lournal of PoliticalEconomy,l4:4 (April

1906),224 235; 'A SocialMuseum for

Chicago', New York Times(19 February

1900),2; 'For a SocialMuseum Here', New

York Times(25 February 1900), t2; 'social

Museum in Paris', New York Times(I9

March I902), 5; 'A SocialMuseum for New

York', New York Times(13 April 1902),

SM4; and Daniel T. Rodgers,Ailantic

Crossings:SocialPolitics in a ProgressiveAge,

Boston: Harvard University Press1998.

2 5 J o h n H . P a tte r so nscr a p b o o kn o .1 1 4 ,

N.C.R. Archive, Archive Center,Dal.ton

History; the frontispiece includes the titles

of nineteenlecturesby Tolman, and pages

l-34 ofthis scrapbookprovide newspaper

coveragefrom his lecturesin the US, and in

England during the 1898-1900period.

2 o - F o r r d i s c u ' :io n o f th e seco m p a n ie sin

relationshipto late nineteenthcentury

global commodity culture, seeMona

Domosh, American Commoditiesin an Age

of Empire,New York: Routledge2006.

l , - ' N r n e l e e nI rr e a I r a r e l Ye a r :Pr e sid e n t

Patterson'sPolicy of "Travel Abroad and

Learn" Fully Carried Out', The N.C.R.

(November 1905),vol. 18 no.8, 243-247

'Slide Room', The N.C.R. (December1906),

66; 'Vice PresidentF.J.Patterson's

EuropeanTrip', The N.CR. (1 November

1 9 0 0 ) ,v o l . 1 3 n o .2 1 , 4 8 5 - 4 8 6 ;' T h e F a cto r y

Lecture in England', The N.C.R. (March

j q O J ) .2 8 0 t ' F a c to r yIe ctu r e in En g la n d ' .

The N.C.R. (February 1905),52; and 'For

B e n e f i to f S t o r e k e e p e r fa

' : cto r l L e ctu r eto

be Given in New York and on the Road',

World N.C.R. (lanuary 1906),35.

'.

rf

AI

Dr. William Howe Tolman, Director of Industrial Betterment, Leaguefor

Social Service of New York, collaborated with Josiah Strong to curate the

materials exhibited in the social Economy Section. Their goal was to use these

documents of progressive social reform as the foundation collection for a

proposed Social Museum, to be founded in New York.2a Although it appears

this museum never did materialize, in the yearsbefore and after the turn of the

century Tolman travelled widely in both the USA and Europe, presenting

illustrated lectures to civic groups on aspectsof industrial betterment. Tolman

may have been initially employed by N.C.R. as a lecturer, basedon a reading of

the Patterson scrapbooks in the N.C.R. archives; his eariy lectures featured

N.C.R. specifically,as when he presenteda slide show of 125 images of N.C.R.

factory life at Madison Square Garden, in New York. According to newspaper

reports, the audience burst into applause at the slides documenting the 'old'

and 'new' ways of women arriving at work, and of changes in lunchroom

accommodations. By the followingyear, Tolman had added other progressive

businessesto his lectures, including Heinz, Cadbury, and Lever Brothers; by

1900, he had founded the League for Social Service to institutionalize

p ro g ressi ve

w orkpl acereform.25

N.C.R. images documenting industrial betterment work also played a

prominent role in the lectures delivered by N.C.R. personnel abroad. These

factory iectures included presentations made by N.C.R. advertising and

publicity personnel, who took multiple-month tours of important sales

territories outside the US, and illustrated lecturesdeliveredby salesmanagersas

part of their lengthy international business trips. Like Heinz, Singer Sewing

Machine, and International Haruester, N.C.R. was a global corporation well

before 1900, with salesagents, and some manufacturing facilities, in Europe,

Asia, Canada, and Latin America by 1905.26President ]ohn H. Patterson

emphasized the centrality of educational trips for company employees,

especially upper management; he himself travelied frequently, including a

year-long trip around the world in 1904-05. As just two examples of the

extensivecirculation of businesspeople outside the US, N.C.R. generalmanager

Hugh Chalmers travelled throughout Europe for five months in 1905, while

E.C. Morse, manager of the Foreign Department, took an eight month trip to

Japan, China, and the Philippines in 1905-i906 to investigate business

conditions.2T The circulation of the industrial betterment images proved

essential in explicating the company's stated mission regarding labourmanagement reiations to numerous audiences abroad, including labour

organizations and reform groups, as well as clients and N.C.R. sales agents

who may have never travelled to the USA, let alone Dayton, Ohio. The Siide

Room of N.C.R. reported they had a busy year in 1905 preparing 'factory

lecture' slide setsfor presentationsin London, Berlin, South America, Australia,

and Japan.

Patterson's primary methodology of visual pedagogy was that of

comparison and contrast. Like other managers in the years before the rise of

industrial sociology in the 1920s,such as Frederic Winslow Taylor and Frank

and Lillian Gilbreth, Patterson was a firm believer in the 'one best way' to

perform any task. Patterson advocatedthe use of photographs to contrast the

'right with the wrong way' of doing things, and a 'before and after' rhetoric

came to dominate much of Patterson'spublicity work documenting the welfare

initiatives at N.C.R. For example, a slideshow of 'before and after' gardening

photographs becamethe basis for the cash prizes Patterson distributed to local

boy gardeners,while lecturers contrasted a photograph of the N.C.R.'s bustling

women's lunch room (figure4b), for example, with the lunchtime practice

before Patterson'sreforms: a female employeeheating her lunch on the radiator

r45

ElspethH. Brown

Figure 4. Beforeand After in the Wornen's

Dining Room:Lunch Pail on Radiator,ftom

Lena Hawev Tracy, How My Heart Sang:

The Storyof Pioneerlndustrial Welfare Work

(N ew Y ork: R i chardR . S m i th, 1950),112,

and unidentified photographer,

INDUSTRIAL PROBLEMS,WELFARE

WORK: UNITED STATES.OHIO.

DAYTON. NATIONAL CASH REGISTER

COMPANY: WELFARE INSTITUTIONS

OF THE NATIONAL CASH REGISTER

COMPANY, DAYTON, OHIO:

CONVENIENCESFOR WOMEN

EMPLOYEES:WOMEN,S DINING

ROOM., ca 1903.Han'ard University Art

Museums,Fogg Art Museum, on deposit

from the CarpenterCenter for the Visual

14.{.4. P ho to: Imagi ng

A rt'. 3.2002.5

Department Cl Presidentand Fellowsof

Haruard College

(figure4a).28As Sharvn Michelle Smith has argued in relationship to Frances

Benjamin |ohnston's Hampton Album images, also included in Harvard's

Social Museum Collection, the rhetoric of the 'before and after' photographic

pairing constructs a narrative of social progress central to the era's reform

movements.2e The contrast of 'before' and 'after' the intervention of

progressive reformers does more than document change over time in the

Iives, for example, of African-American schoolchildren or Ohio factory

workers, The sequencing logic of the image pairing works to close off

alternative readings of history, including those that contested managerial

authority. In this case, for example, the empty dining room signifies the

problem that Patterson faced when he first opened the dining ha1l,where a hot

lunch was free to women workers: no one would use it, for the women saw the

provision of a free lunch as a form of charity, and therefore paternalism. Larger

conflicts, such as the strikes that crippled the company in the early 1900s,are

also rendered invisible through this visual strategy,where an ideology of what

r46

28

Tracey, How My Heart Sang, 120

29- Shann Micl-relleSmith, Amencan

Archives: Gender, Race,and Class in Visual

Ctilture, Pnnceton, NJ: Princeton University

P ress1999.

WelfareCapitalismand DocumentaryPhotography

30- Emily S. Rosenberg,Spreadingthe

AmericanDream: Economicand Cultural

Expansion,1890-1945,New York: Hill and

Wang 1982.

Emily Rosenberghas called 'liberal developmentalism' subordinates contestation to a triumphant narrative of Progress.30

Industrial Bettermentand Sabotage

31 - Tracy, How My Heart Sang,138-139.

32 Michel Foucault,Disciplineand Punish:

The Birth of the Prison,trans. Alan Sheridan,

New York: Vintage Books 1995,200 202.

33- For the lames Ditty material,see

Sealander,Grand Plans,19 and Samuel

CroMher, lohn H. Patterson:Pioneerin

Industrial Welfare,New York: Doubleday

1923, 4-5. lohn Pattersonand his brother

Frank bought a machine in 1883,which

helped them end pilfering in their coal

business;lohn bought controlling interest

in the companythat made the machines,the

National ManufacturingCompany, in 1884.

Many thanks to historian Angela Blake, who

inquired about the bell, and pushed me to

considersurveillancein relationshipto the

aural as well.

34 - Roy W. Johnson and RussellW. L1,nch,

The SalesStrategyof Iohn H. Patterson,

Chicago:Dartnell f932, 20-21, 53.

35- For Patterson'sextensiveforeign

business,which included manufacturing

abroad as early as 1903,seeCrowther, /ofun

H. Patterson,264-284 and fohnson and

Lynch, The SalesStrategyof lohn H.

Patterson,320-325.By 1903,when the

SocialMuseum photographswere estimated

to have been acquiredby Peabody,N.C.R.

h a d s a l e sa g e n t \in th e lo llo r vin gco u n tr ie ::

England (N.C.R.'sfirst agent for nondomesticterritory, hired in 1885);

Germany; Holland; Italy; France; Austria;

Belgium; Spain; Czechoslovakia.

In 1903,

the first German factory was started,in

Berlin. For a recentwork on the relationship

betweenUS basedinternational

corporationsin this period and ideologies

of American empire, seeMona Domosh,

American Commoditiesin an Age of Empire,

New York: Routledge2006.

One of John Patterson's favourite retorts to sceptics,especiallythose in the

businesscommunity, was 'It Pays'. In other words, Patterson argued, N.C.R.'s

financial investment in betterment programmes and in their publicity was

more than returned in reduced labour turnover, higher productivity, and the

eradication of employee sabotage.In fact, |ohn Patterson's interest in visual

technologies, as well as in welfare capitalism, emerged in relation to the

persistent problem of worker sabotage in the early days of the company.

Though this is a connection that N.C.R. rarely made in their public discussions

of their programmes, employee memoirs and archival sourcesdemonstrate the

causal relationship between the destruction of N.C.R. property and the

introduction of a variety of betterment schemes.During 1893, the factory had

been set on fire three times, and in 1894 $50,000worth of cash registerswere

returned from England and Europe because employeeshad destroyed them,

prior to shipment, through the surreptitious application of acid. In response,

Patterson moved his desk into the middle of the factory floor in order to

observemore closelythe mostly male workforce. For the first time, the memoir

of his first Welfare Director Lena Harvey recalled, Patterson took note of

industrial capitalism's daily indignities: the dirty water, the dark factory, the

Iack of lockers, the pervasive filth, and - for women workers - the chronic

sexual harassmentin unlit stairwells on their way to their workstations.rr The

experiencegalvanized Patterson, launching him on the creation of numerous

workplace reforms documented by N.C.R.'s photographs and lantern slides.

Patterson'spresencein the middle of the factory floor, however, meant that

the workers were under direct, daily observation by the company owner.

Though N.C.R. sources stress paternalist good wi1l, a Foucaultian reading

would emphasizePatterson's move as an effort to make 'visibility a trap', to

internalize an obedience to managerial authority even when not under

Patterson'swatchful eye.As Foucault argued, 'he who is subjectedto a field of

visibility, and who knows it 1...] inscribesin himself the power relation in

which he simultaneously plays both roles fof observer and observed, of

supervisor and worker] '.32In this regard, it is worth emphasizingthat the cash

registeritself was designedas a technology of surveillance,which was one of the

main reasonswhy it was so prone to industrial sabotage.The entire point of a

cash register is to compel a clerk to record the cash taken in, and to thereby

prevent the everydayemployee pilfering that was understood to be part of the

moral economy of making ends meet for those who made change on a daily

basis,such as barmen or salesclerks. The first machine, designedby a Dalton

saloonkeeperto prevent his employees'petty theft, featured a cabinet equipped

with keys marked in multiples of five centswith a roll of columned paper; when

pressed,a key punched a hole in the appropriate place on the paper, and the

machine rang a bell. Here we have an aural surveillanceas well: the sound of the

bell alerted the nearby owner-proprietor that his employeehad opened the cash

drawer; no doubt, the sound of that bell would cause any owner to at least

glance in the direction of the register, helping to produce in that series of

gestures exactly the relay of looks that constitute workplace surveillance.-33

Patterson bought controlling interest in the company that made the cash

registersin 1884, after he had used it to discover that a night watchman, fired

two years previously, had been continuing to perform his nightly duties while

cheerfully helping himself to his pay at the end of each evening'sshift.3aAt first,

there was little market for the new invention. But Patterson's senius for sales

147

ElspethH. Brown

and marketing, which helped make the so-called'thief catcher' an international

commodity by the 1890s, also succeeded in circulating a discursive

construction of the employee as untrustworthy, an implicit criminal.rt As a

result, the cash register- like the stop-watch - becamean important symbol of

the battle between labour and capital and, consequently,an ongoing target of

sabotage.s6

Patterson faced the problem of working classhostility outside the factory,

as well as inside it. In the late 1880s,the modest N.C.R. factory was located on

the edge of the city of Dayton, in a poor, working class area known as

'Slidertown'. Few of the local residentshad jobs in the new factory, and local

youths expressedtheir class antagonism by breaking the factory windows,

pulling up the few shrubs Patterson had planted, and even smearing the

delivery trucks, as well as the cash registersthemselves,with mud (figure5;.37

Patterson'ssolution was to hire an Ohio deaconessand Antioch graduate,Lena

Harvey Tracy, to begin what was essentiallya settlement house programme

within N.C.R., for both employeesand neighbourhood residents.Tracy was the

first 'welfare director' in the USA; her work with the local children, as well as in

the factory itself, became a cornerstone for Patterson's industrial betterment

programme.

The factory beautification programme began with Tracy and her

neighbourhood ruffians. In May 1897, Patterson installed her in a newly-built

Pattersonhad

home on the grounds of N.C.R., called'the house of usefulness'.

heard John C. Olmstead speak on his theories of landscape design and had

employed the firm to plan the landscaping;Tracy was directed to work with the

neighbourhood boys to create their own garden plots and, as a result, to

prevent them from destroying Olmstead's work. The N.C.R. photography

l-

S lrrlerto* rr llo r:

36 For example,when NRC rvorkerswere

locked out ofthe factory in 1901in a battle

over unior.rrecognition,a delegatefrom the

NCY bartendersunion announcedin a

C enl ral federatedU ni or r nreeti ngthat i n

support of the locked-out N.C.R. workers,

union bartendersplanned to sabotagethe

cashregistersin their respectivesaloons:

'On a certain day', the delegateannounced,

'it will be found that 10,000cash registers

throughout the greaterNerv York will not

rvork. Then machinists will be sent for to fix

them, but they will get a tip from the union

bartendersand say that they cannot be

repai red.A ccordi ngto l he reporter.the

'secret'dir.ulgedby the bartenders'delegate

'proved too much for the meeting,rvhich

adjourned in a hurry'. 'SaloonKeeperNot

Wanted as Labour Leader',New York Times

,2o \ugust l q0l r, J. Ioh ns onand Ly nc h

describethe relationshipbetweenN.C.R.

and the bartendersas one of open warfare.

Bartendersand clerks,organizedin regional

protectiveassociations,

confiscatedall mail

with the N.C.R. logo or a Da1'tonpostmark,

forcing PattersonIo send mail in plain

envelopesfrom other locations;they refused

accessto traveling salesmenwith their

samplemachines,forcing Pattersonto

resignnew mini-samplesthat salesmen

could carry more surreptitiously.See

fohnson and Lynch, The SalesStrategyof

lohn H. Patterson,83-88.

37- Tracy, How My Heart Sang 101;Fugitt,

'The Trucc B etueenLabourrnd C api tal,

341.

I

* ' ri

ffii

&{:'l i::

148

Figure 5. SlidertownBo1s,ca 1900,lantern

slide. The N.C.R. Archive at Dayton

H i story,C D LS O1Fi g.3 7.

WelfareCapitalismand DocumentaryPhotography

FigUTC6. INDUSTRIAL PROBLEMS,WELFARE WORK: UNITED STATES.OHIO. DAYTON. NATIONAL CASH REGISTERCOMPANY: WELFARE

]NSTITUTIONS OF THE NATIONAL CASH REGISTERCOMPANY, DAYTON, OHIO: LANDSCAPE GARDENING FOR A FACTORY: EMPLOYES,

HOMES, ca 1903.Harvard University Art Museums,Fogg Art X4useum,on deposit from the CarpenterCenter for the Visual Arts, 3.2002.325Photo:

Imaging Department i'. Presidentand Fellowsof Harr.ard College.

149

Ekpeth H. Brown

documented the 'before' and 'after' transformation of the grounds, which

allowed Patterson and Tracey to use the images in slideshows that

demonstrated the 'right' and 'wrong' way to mass plants; how vines could

cover and beautifr fences and sheds; and how ugly backyards could be

transformed into attractive gardens (figure6).38 Olmstead visited the factory

twice in the late 1890s;he supervisedboth the planting of the factory grounds

and some of the model yards of workers' cottagesin the neighbourhood now

known as 'South Park'. An Outdoor Art Committee, selectedfrom the South

Park Improvement Association, factory employees, and the Women's Guild

oversaw the progress of the Olmstead plan, which eventually covered not only

the factory but also ten surrounding blocks including, most importantly, the

front and back yards adjacent to the railway tracks that delivered visitors to

the showcase factory.3e N.C.R. provided vegetable plots for forty of the

neighbourhood boys, and furnished the ground, the seed, the tools, and an

instructor. Apparently, Patterson'sstrategywas successful.According to Tracy,

'soon the very same boys who had refused to wear our badges were getting

themselvesdismissedearly from school in order to appear in the photographs

which were often taken of our factory visitors, together with representativesof

the various clubs, the executivesof the factory, and others'. Here, indeed, was a

compelling 'before' and 'after' transformation: not only gardens,but also the

boy s t hem s e l v e sa,p p e a rre -ma d et fi g u re7 ).an

The documentation of the boys' gardening work became integral to

Patterson's slideshows about the benefits of welfare capitalism at N.C.R.

Patterson'swork here had two main goals: the instrumental effort to remake

the subjectivity of his employeesand neighbours, by creating model workers

and citizens;and the creating of publicity materialsthat would sell the company

as a model factory. As I have discussed, the audiences realized in these

endeavours were multiple, and included N.C.R. employees; Dalton area

residents;visitors to N.C.R.'s model factory al1 potential purchasers of cash

registers;world's fair visitors in the US and abroad - anyone, in other words,

who encountered the company as its representation circulated through

employee magazines,house organs, periodical literature, salesdemonstrations,

or exhibitions on social hygiene.

38- Tracy 114 115;Fugi tt,' The Truc e

BetweenLabour and Capital',342; Shuey'A

Model FactoryTow n', 147-148[145 151].

For a fuller documentationof the boys'

gardeningwork, and of the Olmsted

landscaping more generally, seeArt, Nature,

and the Factory: An Account of a Welfare

Movement, with a Few Remarkson the Art of

the LandscapeGardener,Dalton: National

Cash RegisterCompany 1904

39 Tracy, How My Heart Sang,120-I2I;

Fugitt, 'The Truce BetweenLabour and

Capital', 342; 'Advancesin Landscape

Gardenir.rg',Ihe N.C.R. (January1905),

vol . l u no.1.5-9.

40- Tracy, How My Heart Sang, 126. See

this sectionfor a fuller discussionof the

gardeningwork, and its relationshipto the

Iargermovement for children'sgardensit.t

Progressiveera America.

Figure 7. 'BoysBrigadeEntersSunday

School',from Lena Harvey Tracy, How My

Heart Sang: The Story of Pioneer Industriol

Welfare \{ork (Nerv York: Richard R. Smith,

19s0),189.

150

Welare Capitalismand DocumentaryPhotography

4l - 'Shut l)orvn at Cash RegisterFactory',

New York Times(.4May 1901),9; 'Strike at

Dalton Spreads',New York Times(14 May

1 9 0 1 ) ,2 ; ' D i s g u ste dWith L a b o u r Un io n s' ,

New York Times(.15May 1901),2; 'Dal.ton

Workmen Lose $120,000:National Cash

RegisterCompany'sVersion of the Labour

T r o t r b l e ' ,N e w Y or k f in te s( 4 Ju n e 1 9 0 1 ) ,1 ;

'CaslrRegisterStrike Ends', New York Times

(5 Mar 1902),2. Daniel Nelson discusses

this strike as a harbingerofwl-rathe callsthe

'new factorysystem'of the secondindustrial

revolution, marked by the twin managerial

approachesof scientificmanagementand

welfarecapitalism,in 'The New Factory

Systemand the Unions: The National Cash

RegisterCompany Dispute of I90I', Labour

Hktory 15 (1974), 163 79.

The images documenting N.C.R.'s welfare capitalist initiatives performed

important ideoiogical work while in global circulation. The insistent visual

rhetoric of promise, possibility, and, above all, progress rendered invisible the

contemporaneous political reality of shattered Iabour relations in Day.ton.

Indeed, in the midst of a widely-publicized ten-month lockout in 1901,

Patterson went on an extended tour of Europe where he used his image

collection to publicize N.C.R.'s betterment work - at the same time that five

thousand workers had walked off the job to support the N.C.R. moulders, who

were striking for union recognition.4t While Patterson's welfare capitalist

initiatives were laudable under pretty much any standard,especiallyin the years

before the codification of Progressive-erastate regulation, it is the cultr-rralwork

of photographic documentation that we may wish to emphasizein a collection

of essaysconcerning the circulation of photographs. In the effort to provide

documentation of progressivereform, I suggest,these images erase a messier

history of contestation over the details of industrial capitalism. In erasing this

history, the N.C.R. images function not so much as commodity fetishes as

visual ones: they emphasize the exchange value of Progressive-erareform

knowiedge production over the use value of - to take just one example industrial sabotage.Details central to the production of both the images and

the cash registers(such as the seven hand-colouring women in the Photo

Department, or the striking moulders of 1901) disappearfrom the audience

view, to be replacedby an early form of corporate public relations imagery that

doubled as object lessons in Progressive-erareform for a socially engaged,

middle-classoublic.

ll

itl

irh.

l5l