Regional Cooperation in Transportation Planning

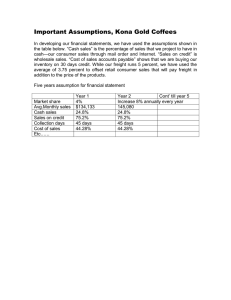

advertisement