Differences in English Language Proficiency, Self

advertisement

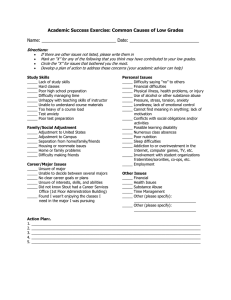

Differences in English Language Proficiency, Self-Efficacy, Anxiety, Coping, and Psychological Wellbeing between Educationally Well and Less Well Adjusted Thai Students Enrolled in First Year University English Language Courses Yeo Hoon Kim1 Graham Davidson2 Robert Ho3 2 Assumption University 3 Assumption University 1 Yeohoon.k@phuket.psu.ac.th Abstract The aim of this research was to examine the connection of English language proficiency, foreign language anxiety, English language self-efficacy, educational motivation, coping and psychological wellbeing with educational adjustment of Thai students enrolled in first year university English language courses. In addition, effects of participants’ gender, Faculty, year of study, and residential arrangements on these linguistic, psycho-educational, motivational, and wellbeing variables were assessed. A total of 470 students from Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus taking first-year introductory English courses in the academic year of 1/2011 completed a self-report questionnaire designed to measure the above variables. The questionnaire was translated into, and then administered in, Thai using a combination of the back-translation and committee techniques, followed by field testing. Results of a General Linear Modeling Multiple Analysis of Variance indicated that better educationally adjusted students on average also reported less foreign language anxiety, higher English language self-efficacy, higher educational motivation, more active and avoidant coping but less emotional coping, and fewer symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress than educationally less well adjusted students. However, the groups did not differ on average in terms of English language proficiency. Significant gender, Faculty, and year of study differences were observed for English language proficiency, foreign language anxiety, English language self-efficacy, motivation to develop talents for a chosen occupation, and aspects of coping. It was concluded that availability and use of psycho-educational and counseling assistance would benefit NESB first year university students in reducing foreign classroom language anxiety, increasing English language selfefficacy, increasing motivation, and reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. Such support and assistance is equally important as, if not more important than, English language instruction in raising students’ level of educational adjustment and ultimately improving their chances of academic success. Keywords: Thai students, First year university, English language proficiency, Wellbeing, Educational adjustment 1. Introduction The first year university experience can be problematical for many students. It is the most vulnerable period for students in terms of probability of academic failure, dropping out of study, and increased social and emotional difficulties [1]. Positive adjustment to University is a critical factor in influencing students’ academic success [2]. Entrance to university symbolizes a challenging transitional step in young peoples’ lives. For many, successful separation from parents and family and establishment of emotional independence have a positive influence on educational adjustment [3] [4]. Students need to deal with more responsibilities and challenges upon entering university. They face more complex and demanding changes and challenges than they experienced in their high school years, many of which relate directly to their ability to come to terms with university courses, teachers, and library use [5]. In universities where the medium of instruction is English, the academic and social lives of students from non-English speaking backgrounds (NESB) are influenced by their level of English language proficiency [6]. For example, Swagler and Ellis [7] found that Taiwanese students in the United States reported that English language proficiency was their major educational obstacle. The role that English language proficiency plays in students’ adjustment to university is particularly relevant in the Thai university context, where most new programs to be opened in future are likely to be international programs [8]. First year Thai university students enrolling in such programs, who have limited English proficiency, therefore, are likely to take remedial English courses with no credit, while Thai students in such programs, who have greater English proficiency, will be allowed to enroll in first compulsory English courses with credits. Hence, the students with greater English proficiency are more likely to progress faster through university. However, all Thai students enrolling in these new programs will be confronted by the challenge of learning, and learning in, English as their second language as they embark on their university studies. Lower levels of English language proficiency not only affect students’ academic progress but also their experience of university life in general. Dowdy and colleagues [9] found that the students with lower levels of English proficiency tended to have more school-related problems, such as attention and learning difficulties. Students’ limited English language proficiency also limited their desire to seek social interactions [10]. In addition to language proficiency, a range of psycho-educational and psychosocial factors are likely to play a role in educational adjustment. For a start, educational self-efficacy is a reliable predictor of students’ motivation and learning [11]. Self-efficacy is a closely related concept to self-concept; however, self-efficacy is a better indicator of level of students’ belief in their ability and subsequently of their educational performance [12]. Linguistic self-efficacy (one’s belief in specific aspects of one’s linguistic capability) contributes positively to language learning motivation. Developing a sense of linguistic self-efficacy early on in language learning tends to benefit students’ performance [13]. Linguistic self-efficacy, in turn, may be a function of gender. Research suggests that males’ self-efficacy tends to be stable regardless of level of difficulty of the task in question. Females’ self-efficacy is more likely to fluctuate so that, when females are confronted with more difficult tasks, their level of self-efficacy declines, but it increases when dealing with less difficult tasks [14]. Anxiety is often correlated with second language learning [15] so that foreign language anxiety may limit students’ effective acquisition of a second language [16] [17]. Gardner and Lambert [18] rated this motivational factor of foreign language anxiety as one of the top two factors (the other being linguistic aptitude) in second language learning. Less anxious learners tend to be more enthusiastic, engaged, and focused. They are interested in what they are doing and they try hard to overcome challenges of second language acquisition [19]. Bacon [20] investigated relationship between gender and foreign language learning. Males tended to use different coping strategies according to the level of difficulty of the language learning task. They were more likely to use more active coping techniques when dealing with more difficult learning problems. However, females continued to use similar coping techniques regardless of level of difficulty of the learning task. Motivation and coping are related processes, so that coping style may also influence educational motivation. Furthermore, problem-focused coping strategies may play a positive role in students’ motivation and academic performance [21]. Problem-focused, or active, coping helps students to pay attention to specific goals and allows them to view the situation as more controllable; hence active coping is positively related to psychological well-being and academic success. In contrast, students who engage in avoidant coping tend to view the situation as less controllable and are less likely to achieve success and exhibit positive psychological well-being [22] [23]. Educational motivation refers to students’ beliefs about what is important in academic situations [24]. The decade long study of Krause and colleagues [25] found that the highly motivated students produced better academic results. Kuh [26] also found that motivation and average grades are positively related. Among C grade average students, 42% were highly motivated. This percentage increased as grades increased. About 70% of the B grade average students rated themselves as highly motivated, and 79% of the students who achieved an A grade rated themselves as highly motivated. Kuh concluded that highly motivated students tend to perform better academically than poorly motivated students. Moreover, the absence of motivation is associated with poor psychosocial adjustment to university life, high levels of perceived stress, and poor general wellbeing [27]. Mental health and academic performance are closely related. Students with low selfefficacy tend to focus on how difficult school life might be and doubt if they are able to manage their studies. Therefore, they tend to experience more stress [28]. Problems with second language learning can be one of the stressors [29]. Moreover, students with higher levels of general anxiety assess the situation as a threat and as unmanageable, which often leads to poor academic adjustment and failure [30]. Students’ residential arrangements during term time may also influence their educational adjustment. Students who are living somewhere other than where they previous called ‘home’ are less likely to adjust to the demands of university study. Students who are no longer living at home following their entrance into university experience lack of parental support. They are more vulnerable to psychological symptoms such as depression [31]. Hysenbegasi and colleagues [32] found that almost half (48%) of depressed students reported lower levels of academic performance. Although there is a considerable amount of research into students’ adjustment to the first year of university as well as into learning in a second language such as English, little research has been done with NESB students who are required contemporaneously to adjust to first year university and at the same time to an English language classroom environment. Furthermore, the majority of research into foreign language learning has been conducted with NESB college and university students studying abroad. The current research, therefore, aimed to: (a) Examine the connection between English language proficiency, English language selfefficacy, foreign language anxiety, coping strategies, mental health, educational motivation and educational adjustment among Thai-speaking students enrolled in first year university English language courses at Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus; (b) Provide a more thorough understanding of the educational adjustment of these students who are going through a transitional period (first year) of adjusting to university where the English language medium of instruction is not their first language; and (c) Explore the effects of gender, faculty, year of study, and residential arrangements on educational adjustment and related psychoeducational and psychosocial factors. 2. Method 2.1 Participants The participants were 477 Thai speaking students of Prince of Songkla University, Phuket Campus taking first-year introductory English courses in the academic year of 1/2011. Students whose first language was not Thai were excluded from the study. Prior to data analysis, seven participants’ questionnaires were eliminated from the sample because they failed to complete all or a major part of one or more questionnaire components, leaving a final sample of 470 (364 females, 104 males; 2 unspecified) for analysis. Participants were drawn from the Faculties of International Studies (n = 212) and Hospitality and Tourism (n = 256; 2 unspecified). The sample consisted of first year (n = 295) and second to fourth year (n = 173; 2 unspecified) students. Participants either lived at home with family or relatives (n = 82), or in shared or single occupancy private accommodation (n = 25), or in the university dormitory (n = 332; 31 unspecified). 2.2 Materials The self-report questionnaire recorded students’ gender, age, Faculty, year of study, previous university experience, residential arrangements, and TOEIC score, which was used as a measure of English language proficiency. English language self-efficacy was measured by 4-question scale developed by the researcher. Students rated their belief in their ability to understand, speak, read and write English on a 5point scale from 1 (not at all) – 5 (excellent). Internal reliability in the form of Cronbach’s alpha (α) = 0.78. The 33-question Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale [15] was used to assess foreign language anxiety. Students rated their level of foreign language anxiety from 1 (strongly agree) – 5 (strongly disagree). Seven items were reverse scored, so that a low score on each item consistently reflected heightened foreign language anxiety. Following removal of one item, internal reliability (α) = 0.90. The 16question Brief COPE [33] was used to measure active, avoidant and emotional coping. Students rated their use of particular strategies from 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) – 5 (I’ve been doing this a lot). Internal reliabilities (α) respectively for active, avoidant, and emotional coping = 0.77, 0.74, and 0.80. Psychological wellbeing in the form of stress, anxiety and depression was measured by Thai version of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) 21 [34] [35]. Students rated their symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression from 0 (did not apply to me at all) – 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). Internal reliabilities (α) respectively for stress, anxiety and depression = 0.84, 0.78, and 0.79. Two items were used to assess educational motivation. The first item asked students about getting themselves motivated to study and the second inquired about developing their talents for their chosen occupation. Students rated their motivation from 1 (strongly agree) – 5 (strongly disagree). Internal reliability (α) = 0.40 was low and therefore these items were entered separately into the data analyses. Finally, the First Year Experience Questionnaire [36] [37] was used to measure educational adjustment. Students rated themselves on 37 items measuring academic and personal/emotional adjustment and engagement with university study from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Ten items were reverse scored so that a high score indicated greater educational adjustment. Internal reliability (α) for the full scale score = 0.86. 2.3 Procedure 2.3.1 Translation The original questionnaire was constructed in English except for the Thai version of the DASS21 [35]. In order to maximize NESB Thai speakers’ comprehension, the English sections of the questionnaire were translated from English to Thai [36]. A combination of the back-translation technique and the committee approach was used in translation. After the translation had been completed, a field test was conducted separately with two bilinguals to ensure that translated items and instructions were comprehensible [37]. 2.3.2 Data Collection Students of the Faculties of International Studies and of Hospitality and Tourism enrolled in first year English courses were visited by the researcher in their classrooms. An information sheet was provided and the research procedure was explained verbally, including an explanation about the identity of the researcher, general purpose of the research, voluntary nature of students’ participation, and the anonymity of their responses. The approximate time for completion of the questionnaire was 20 minutes. 3. Results Gender, Faculty, year of study, and residential living differences in English language proficiency, foreign language anxiety, educational motivation, and psychosocial functioning were assessed separately by 1-way General Linear Modeling Multiple Analysis of Variance (GLM MANOVA). Significant differences are shown in Table 1. Table 1 Gender, Faculty, Year of Study, and Educational Adjustment Difference in English Language Proficiency, Foreign Language Anxiety, Educational Motivation, and Psychosocial Functioning Variable Gender TOEIC FLA CS_EM ELSE Faculty Mean (M) M M Male Female 366.58 330.30 98.52 93.11 6.16 6.77 11.36 10.26 M FIS M FHT TOEIC EM_OCC FLA CS_ACT CS_AVOID CS_EM EA ELSE Yr of Study 314.49 4.02 91.92 18.68 19.20 6.92 126.77 10.26 M 1st TOEIC EM_OCC FLA EA ELSE Educational Adjustment TOEIC EM_STUDY EM_OCC FLA CS_ACT CS_AVOID CS_EM DASS_STR DASS_ANX DASS_DEP ELSE 324.73 4.18 93.00 130.93 10.39 M Low 356.21 4.21 96.19 19.50 19.94 6.25 130.60 10.85 M 2nd 4th 359.74 4.05 96.47 125.78 10.92 M High 336.05 3.14 4.00 90.99 18.21 18.75 6.97 8.66 6.36 6.13 10.25 340.33 3.45 4.26 97.66 20.06 20.35 6.12 6.61 5.07 3.87 10.93 F (df = 1, 429) 17.59*** 9.62** 4.13* 17.48*** (df = 1, 430) 33.51*** 9.20** 8.32** 8.24** 4.79** 10.00** 7.40** 8.40** (df = 1, 429) 21.96*** 3.98* 5.20* 13.03*** 6.28* (df = 1, 432) 0.33 ns 12.72*** 18.84*** 21.40*** 45.91*** 32.48*** 16.85*** 20.56*** 10.85** 39.78*** 11.74** Note: TOEIC = Test of English for International Communication; EM_STUDY = Motivation to study; EM_OCC = Motivation to develop occupational talents; FLA = Foreign language anxiety; CS_ACT = Active coping; CS_AVOID = Avoidant coping; CS_EM = Emotional coping; DASS_STR = DASS21 Stress; DASS_ANX = DASS21 Anxiety; DASS_DEP = DASS21 Depression; ELSE = English Language Selfefficacy; Low score = Increased foreign language anxiety; *** p < .001; ** p < .01; * p < .05; ns = p > .05 Gender differences were significant overall, F (df 12, 429) = 5,478.02, p < .001. Table 1 shows that male students on average had higher TOEIC scores (p < .001), less foreign language anxiety (p < .01), greater English language self-efficacy (p < .001), but engaged in less emotional coping (p < .05) than female students. Faculty differences were significant overall, F (df 12, 430) = 7,739.71, p < .001. Table 1 shows that students from the Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism on average had higher TOEIC scores (p < .000), higher motivation to develop occupational talents (p < .01), lower foreign language anxiety (p < .01), higher English language self-efficacy (p < .01), better educational adjustment (p < .01), greater use of active coping (p < .01), greater use of avoidant coping (p < .01), but less use of emotional coping (p < .01) than students from the Faculty of International Studies. Differences between first year and advanced level (2nd – 4th year students were significant overall, F (df 12, 429) = 7,183.52, p < .001. Table 1 shows that advanced level students on average had higher TOEIC scores (p < .001), less foreign language anxiety (p < .05) and higher English language self-efficacy (p < .05) than first year students. However, on average they also had lower motivation to develop occupational talents (p < .05) and poorer educational adjustment (p < .001) than first year students. Differences between students with different living arrangements were significant overall, F (df 12, 399) = 2,545.51, p < .001. However, the difference was reliable only for foreign language anxiety scores (p < .05). Students living in the dormitory (M = 93.26) on average had greater foreign language anxiety than students living privately with friends or alone (M = 102.61, p < .05). Participants were divided into two groups (low vs. high educational adjustment) based on whether their educational adjustment (EA) score fell below or above the mean score (M = 125.52) for that measure. Students deemed to have low EA were then compared with those deemed to have high EA using a 1-way GLM MANOVA with EA (low vs. high) as the independent variable and English language proficiency, foreign language anxiety, English language selfefficacy, coping, educational motivation and psychosocial functioning as the dependent variables. There was a significant difference overall between the low EA and the high EA group, F (df 11, 432) = 6,931.85, p < .001. Table 1 shows that students in the high EA group, when compared with students in the low EA group, on average: were more motivated to study (p < .001) and to improve their occupational talents (p < .001); had less foreign language anxiety (p < .001) and greater English language self-efficacy (p < .01); engaged in more active (p < .001) and avoidant (p < .001) but less emotional coping (p < .001); and were less stressed (p < .001), less anxious (p < .01), and less depressed (p < .001). In contrast, the high EA group did not differ significantly from the low EA group in terms of English language proficiency, as measured by TOEIC (p > .05). 4. Discussion The research reported here aimed to examine the connection between English language proficiency, English language selfefficacy, foreign language anxiety, coping strategies, mental health, educational motivation and educational adjustment among Thaispeaking students enrolled in first year university English language courses. It also aimed to provide a better understanding of these students’ educational adjustment to university life when the English language medium of instruction is not their first language. Using a Mean split to distinguish between students deemed to be low or high on educational adjustment, the results showed that students with high adjustment were more motivated, had higher English language self-efficacy and lower foreign language anxiety, used more active and avoidant but not emotional coping strategies, and had fewer symptoms of stress, anxiety and depression than students with low levels of educational adjustment. By comparison, differences in educational adjustment were not based on differences in English language proficiency, as measured by TOEIC. The implication of these findings is that psycho-linguistic factors such as foreign language anxiety and self-efficacy, psychoeducational factors such as motivation to study and prepare for a career, and psychosocial factors such as coping style and psychological wellbeing may be more important determinants of educational adjustment and ultimately educational success than English language proficiency itself. Notwithstanding, a number of demographic differences in English language proficiency emerged. Males on average were more proficient in English (i.e., they scored higher on TOEIC) than females. Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism students on average were more proficient in English than Faculty of International Studies students. Second – fourth year students on average were more proficient in English than first year students. However, males on average were not better educationally adjusted than females; and second – fourth year students on average were less educationally adjusted and reported less motivation to prepare for a career than their first year counterparts. Foreign language anxiety and English language selfefficacy consistently differentiated between these demographic groupings with males, Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism students, and advanced year students reporting less classroom language anxiety and more English language self-efficacy than their female, Faculty of International Studies, and first year counterparts. The use of emotional coping strategies, e.g., seeking emotional support, venting emotions, focusing on emotions, invoking religion, and resorting to humor, which is associated with lower educational adjustment, reliably distinguished between males and females as well as between students from the two faculties, with females, and Faculty of International Studies students being more likely to attempt to cope emotionally. The interaction effects between these demographic variables on English language proficiency and on related psycho-educational and psychosocial concomitants bear further scrutiny with a larger sample. Male, Faculty of Hospitality and Tourism, and first year students on average did not differ from female, Faculty of International Studies, and advanced year students in terms of levels of stress, anxiety and depression; but students who scored lower on educational adjustment on average also scored higher on stress, anxiety and depression than students who scored higher on educational adjustment, clearly establishing a link between these symptoms of psychological wellbeing and educational adjustment. However, it is important to note that depression levels in these groups on average were normal – mild, stress levels on average were mild, and anxiety levels on average were moderate. Nevertheless, 15% of the sample reported severe symptoms of stress, 26.2% reported severe symptoms of anxiety, and 8% reported severe symptoms of depression. Universities have a duty of care to their students in distress, as well as a duty to maximize students’ chances of academic success by providing counseling services that offer support for students in need. Despite previous research [31], neither students living alone or with others in private accommodation nor dormitory students on average showed more symptoms of psychological distress than students living at home or with extended family. 5. Conclusions Students need assistance in understanding and dealing with transition to university, especially in their first year. It is essential for educational institutions to provide psychological support to those students experiencing difficulties in adjusting to their new learning environment [38]. Developing and facilitating various programs and interventions that address factors which may lead to positive educational adjustment is essential for students’ educational adjustment and success, as well as for student retention [10]. Availability and use of psychoeducational and counseling assistance would benefit students in: reducing foreign classroom language anxiety; increasing English language self-efficacy; increasing motivation to study and to improve one’s occupational talents; and reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. Such benefits are likely to result in better educational adjustment and subsequently in better student retention and educational success. Of lesser importance for NESB students’ educational adjustment in their first year of university is their level of English language proficiency, although female students and students from specific Faculties such as International Studies may benefit exponentially from additional English language learning support. Second – fourth year students who are repeating the first year of English language study require additional assistance to focus motivationally on enhancing their talents for a future career and on adjusting academically and personally to engagement with university study. 6. Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Emeritus Professor Graham Davidson. I also would like to thank Dr. Vorapot Ruckthum and Ms Ok Won Kim for their support and encouragement, and Ajarn Supachai Sangpunya, Ajarn Somjate Srirabai, Ajarn Napacha Prapawadee, Ajarn Woralak Bancha, and Ajarn Sudarat Srirat for their expert support for the research. References Journal Papers [1] McInnis, C. (2001). Researching the first year experience: Where to from here? Higher Education Research & Development, 20, 105-114. [2] Gan, Y., Hu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2010). Proactive and preventive coping in adjustment to college. The Psychological Record, 60, 643–658. [3] Lapsley, D. K., Rice, K. G., & Shadid, G. E. (1989). Psychological separation and adjustment to college. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 286-294. [4] Hoffman, J. A. (1984). Psychological separation of late adolescents from their parents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 170-178. [5] Eaele, E. E. (1936). The adjustment problems of college freshmen and contributory factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 20, 60-76. [6] Khawaja, N. G., & Dempsey, J. (2007). Psychological distress in international university students: An Australian study. Australian Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 17, 13–27. [7] Swagler, M. A., & Ellis, M. V. (2003). Crossing the distance: Adjustment of Taiwanese graduate students in the United States. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 420–437. [8] Wiriyachitra, A. (2002). English language teaching and learning in Thailand in this decade. Thai TESOL Focus, 15(1), 4-9. [9] Dowdy, E., Di Stefano, C., Dever, B. V., & Chin, J. K. (2011). Screening for emotional and behavioral risk among students with limited English proficiency. School Psychology Quarterly, 26, 14-26. [10] Olivas, M., & Li, C. S. (2006). Understanding stressors of international students in higher education: What college counselors and personnel need to know. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 33, 217-222. [11] Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 82–91. [12] Tremblay, P. F. & Gardner, R. C. (1995). Expanding the motivation construct in language learning. The Modern Language Journal, 79, 505-518. [13] Cotterall, S. (1999). Key variables in language learning: What do learners believe about them? System, 27, 493-513. [14] Bacon, S. (1992). The Relationship between gender, comprehension, processing strategies, and cognitive and affective response in foreign language listening. The Modern Language Journal, 76, 160-178. [15] Horwiz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125132. [16] Horwitz, E. K. (1986). Preliminary evidence for the reliability and validity of a Foreign Language Anxiety Scale. TESOL Quarterly, 20, 559-562. [17] Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 112-126. [18] Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second-language acquisition. Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie, 13, 266-272. [19] Garris, R., Ahlers, R., & Driskell, J. E. (2002). Games, motivation, and learning: A research and practice model. Simulation and Gaming, 33, 441-467. [20] Bacon, S. (1992). The Relationship between gender, comprehension, processing strategies, and cognitive and affective response in foreign language listening. The Modern Language Journal, 76, 160-178. [21] Struthers, C. W., Perry, R. P., & Menec, V. H. (2000). An examination of the relationship among academic stress, coping, motivation, and performance in college. Research in Higher Education, 41, 581-592. [22] Park, C. L., & Adler, N. E. (2003). Coping style as a predictor of health and well-being across the first year of medical school. Health Psychology, 22, 627-631. [23] Ben-Zur, H. (2009). Coping styles and affect. International Journal of Stress Management, 16, 87–101. [24] Fadlelmula, F. K. (2010). Educational motivation and students’ achievement goal orientations. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2, 859-863. [26] Kuh, G. D. (2007). What student engagement data tell us about college readiness. Peer Review, 9, 4-8. [27] Baker, S. R. (2004). Intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivational orientations: Their role in university adjustment, stress, well-being, and subsequent academic performance. Current Psychology: Developmental, Learning, Personality, Social, 23, 189-202. [28] Zajacova, A., Lynch, S. M., & Espenshade, T. J. (2005). Self-efficacy, stress and academic success in college. Research in Higher Education, 46, 677-706. [29] Misra, R., Crist, M., & Burant, C. J. (2003). Relationships among life stress, social support, academic stressors, and reactions to stressors of international students in the United States. International Journal of Stress Management, 10, 137–157. [30] Cohen, M., Ben-Zur, H., & Rosenfeld, M. J. (2008). Sense of coherence, coping strategies, and test anxiety as predictors of test performance among college students. International Journal of Stress Management, 15, 289–303. [31] Tognoli, J. (2003). Leaving home. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 18:1, 3548. [32] Hysenbegasi, A., Hass, S. L., & Rowland, C. R. (2005). The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 8, 145-151. [33] Welbourne, J. L., Eggerth, D., Hartley, T. A., Andrew, M. E., & Sanchez, F. (2007). Coping strategies in the workplace: Relationships with attributional style and job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 312-325. [34] Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large nonclinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. [35] National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research. (2007). DASS21 (Thai version). Sydney, Australia. Downloaded on 1 May 2011 from http://www2.psy.unsw.edu.au/groups/dass/T hai/NCHECR_Thai.htm [36] Ji, L-J., Zhang, Z., & Nisbett, R. E. (2004). Is it culture or is it language? Examination of language effects in cross-cultural research on categorization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 57-65. [37] Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of CrossCultural Psychology, 1, 185-216. [38] Randall, M., Naka, K., Yamamoto, K., Nakamoto, H., Arakaki, H., & Ogura, C. (1998). Assessment of psychological stressors and maladjustment among foreign students of the University of the Ryukyus. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 52, 289-298. Books and Monographs [25] Krause, K-L., Hartley, R., James, R., & McInnis, C. (2005). The first year experience in Australian universities: Finding from a decade of national studies. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government Department of Education, Science and Training. [36] McInnis, C., & James, R. (1995). First year on campus: Diversity in the initial experience of Australian undergraduates. Canberra, Australia: AGPS. [37] Vernon-Livington, N. (2009). Influence of parenting and coping styles on adjustment to first year university. Unpublished Bachelor of Social Science (Psychology) (Honours) Dissertation, University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia.