The History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust: An

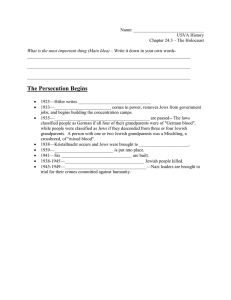

advertisement

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

West Chester, Pennsylvania

Tuesday, November 14th, 2006

Professor Madeleine Wing Adler

President of the University

Professor Jonathan Friedman

Director f Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Esteemed Members of the Faculty

Esteemed Students

Ladies and Gentlemen

Back in 1969, around 11 am during a sunny New York day, my cousin, Professor Guy Benrubi, and

I, both students at New York University at the time and Guy sporting a beard, were walking on the

vast Brooklyn Court Plaza–Brooklyn Civic Center. The Plaza was almost deserted save for a

pretzel vendor who had strategically parked his cart in the middle of the square. To both of us it

was obvious that he was Greek even from far away. We approached him and Guy asked for a

pretzel, in Greek naturally. His spontaneous and exclamatory reply, with a slight hint of relief, was:

« And I mistook you for Jews! » This event was aired, by me, during a special documentary series

on Greek State Television (ET3) a couple of decades later. Today, as then, I stand before you as

both a Greek and a Jew.

My objective this evening is to offer a glimpse of Jewish Thessaloniki with special emphasis to the

Holocaust. This vast topic may be broadly divided into the following subtopics: 1) The history of

Jewish Thessaloniki up to the Holocaust, 2) The Holocaust of the Jews of Thessaloniki and 3) The

aftermath and the creation of the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki. Therefore the most appropriate

title for this work is:

The History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust: An Exposé

The goal to which I aspire this evening is to provide a sequence of historical events and, by doing

so, to attempt to stimulate your interest in further research. You will be surprised, doing a cursory

non-web or web based research, of how little we know, and, that most scholarly or non-scholarly

published work, in most instances, just repeats a bare minimum of facts and data. Thus one might

be tempted to believe that the subject, especially that of the annihilation, is taboo. Gaps in the

historiography of Greece do a disservice both to the remaining Jewish Greeks in particular and the

whole Hellenic Nation in general. It is encouraging that research has picked up lately, albeit at a

slow speed. Nevertheless, it is a welcome step in the right direction. The main reason that research

should accelerate at full speed is the inescapable reality of the biological attrition of the ranks of

eyewitnesses and holocaust survivors.

For completeness, the Abstract of the presentation follows:

Abstract

Jewish Thessaloniki is unique because the most cataclysmic and momentous event in its 2,000 year

history is its (near total) obliteration. Unfathomable events of human annihilation took place within

a space of a few months in 1943 CE. These events have been only superficially researched as to the

interplay of circumstances and powers that allowed them to take place, to the degree and speed they

occurred. Documentary evidence shows the bureaucratic efficiency of the perpetrators. The events

of the Holocaust of the Jews of Thessaloniki should be correlated with the history of the

Community before AND after the destruction. The question is twofold: if more human beings

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 1 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

could have been saved and, irrespective of the outcome, what was the moral standing of the

surroundings of the Community? The latter, for objective purposes, can only be surmised and

deduced by the behavior, attitude, actions, reactions and / or omissions of the non–Jewish

community, as a whole and as individuals, BEFORE and AFTER the Holocaust. Unfortunately the

general Holocaust mathematical equation has two parts: The first equality states that it only takes a

few evil persons to assassinate [too] many. The second equality states that many righteous humans

may save, at most, a finite number of fellow beings. Darfur waits our actions. . .

Introduction

The history of the Jewish presence in Thessaloniki may be partitioned in the following time periods:

A) From the Ancient times up to 1492 CE, B) From 1492 to the occupation of Thessaloniki by the

German Armed Forces in April 9, 1941, C) The period of the German Occupation [April 9, 1941 to

October 30, 1944] and, last, D) From the date of Liberation to the present. The History of Jewish

Thessaloniki up to the Holocaust is comprised by time periods A and B. The History of the

Holocaust of the Jews of Thessaloniki includes time period C but ends on May 8, 1945 with the

final liberation of all German Concentration and Death Camps.

The Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki came into existence in order to fulfill the need to preserve the

historical memory, to offer vivid glimpses of the past, to educate current and future generations and

serve as a depository of knowledge and tradition for the living Community. It aspires to be the

cradle of our heritage. The demanding task of building the future of the Community based on its

past legacy and wealth of particular traditions in all spheres of human activity is daunting, let alone

realizable. However, one might transubstantiate hope to miracle and believe that the future

generations will prove the wartime perpetrators wrong!

The History of Jewish Thessaloniki up to the Holocaust

A. From Ancient Times up to 1492 CE

Starting with the first period of history, and lacking any precise indications, we assume that the

Jewish presence was established with the arrival of Jews from Alexandria, Egypt around 140 BCE.

Those Jews that settled the geographic area of Modern Day Greece came to be known as

1

Romaniotes, a typical example of a Jewish community of the Hellenistic and Roman era . They

adopted the Greek language, retaining and incorporating elements of Hebrew and Aramaic, as well

as the Hebrew script. Their names were Hellenized and the oldest and most contiguous Romaniote

Community, up to the Holocaust [1944], was the one of Ioannina (or Janina) in the Epirus district.

We have the first written proof of a Jewish presence in Thessaloniki as a result of the visit by Saul

of Tarsus, better known as Apostle Paul. Apostle Paul preached at the Synagogue during his stay in

Thessaloniki. The Synagogue, according to tradition, was called «Ets Ahaim», The Tree of Life.

For many centuries Thessaloniki was initially part of the Roman Empire and later part of the

Byzantine Empire. The city and its citizens were subject to the fortunes and misfortunes that befell

the Empire. A dividing date mark of the first period (i.e. till 1492) is March 26, 1430, the day when

Thessaloniki fell to the Ottoman Turks. Concerning its Jewish inhabitants, they shared the same

fate as their co-religionists all over the Empire: First, during the Roman era, they enjoyed wide

autonomy which was curtailed when Byzantium took hold, along with the establishment of

Christianity as the state Religion. It is to be noted that Thessaloniki is second only to

Constantinople [Istanbul] in the number and importance of Byzantine monuments, mostly

2

Churches .

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 2 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

It is during this period [1376] that the first settlement of Ashkenazi Jews is established. They

originate, persecuted, from Hungary and Germany, and they continue to arrive for the next couple

3

of centuries . Even though restrictive measures were instituted against the Jews by a succession of

Byzantine Emperors, overall, Jews were allowed to live in relative freedom and according to the

laws and traditions of their religion and continue to develop and enrich their unique heritage. They

also arrived from Provence, from the mainland Italian Peninsula, as well as Sicily. The multitude of

places of origin was reflected in the names of their respective houses of worship which betrayed

geographical origin.

The conquest of Byzantine Thessaloniki by the Ottoman Turks transformed, in part, the character of

the city to one, where, the new Muslim element of the population was, if not the most numerous

most of the time, the most privileged and dominant. Sultan Murat II will introduce administrative

rules for the city to function. These include the granting of certain privileges such as communal

autonomy and various tax exemptions, to both Jews and Christians alike.

This event prepares the local Jewish population for the most pivotal event in its almost two

millennia history, that of the settlement of the first contingent of perhaps 15000 to 20000 Jews from

Spain, the so called Sephardic Jews [Sepharad means Spain] in the year 1492, as a direct

consequence of the Spanish Catholics King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella who, in a Royal Edict on

March 13, forced all Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave the Country. That is why this

45

Edict is also known as the Expulsion Edict . Thus the settlement of those refugees in Thessaloniki

effectively concludes the first time period of the History of Jews in Thessaloniki.

B. From 1492 to April 9, 1941

The presence of Jews, refugees from Spain, marks the beginning of the second period in the history

of Jewish Thessaloniki. Spanish Jews will settle in all seaside urban centers of the Ottoman Empire

after they were extended a welcome by Sultan Vayazit II. One of the goals of the Sultan might have

been to repopulate and revitalize Thessaloniki which, by 1492, was in decline and depopulated.

The invigoration of the dormant city by the new arrivals changes again its character, injecting it

with the Sephardic tradition and Spanish language, which will uniquely define its Jewish population

to the day.

Again there is an influx of various Jewish groups during the 16th and 17th centuries, coming from all

over: from Portugal, after they have been expelled as in Spain, from Poland, Hungary, Italy and

North Africa. The dominant Sephardic element prevailed over all newcomers, Sephardic or

otherwise. Cultural growth along with economic growth will last until the beginning of the 17th

Century. New sea routes as well as the involvement of the Ottoman Empire in military campaigns

will bring economic malaise and cultural decline.

The 17th century is marked by the appearance of Sabbetai Sevy [or Sabathei Tzevi, or Cevy] of

Smyrna (modern day Izmir) declaring himself to be the long – expected and awaited Messiah, self

appointed King of Israel and Savior of the Jewish people. His message will be heeded by Jews all

over Europe since yearning for deliverance from oppression facilitated the acceptance of his

6789

claim

. The result for Thessaloniki was the splitting of the Community to believers and nonbelievers. When the Ottoman authorities forced him to convert to Islam [ascertaining authority], a

few hundred families followed him into conversion and thus created the complex minority of

«Judeo-Muslims», or Donme [«Turncoats»] or, as they prefer to be called, the «Ma’mim» i.e. the

Believers. Jumping ahead, this peculiarity of being outwardly identified as Muslims saved them

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 3 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

from the German’s wrath since they were «exchanged» [expelled] from Greece as Muslims in the

1923 population exchange with Turkey.

As was to be expected, this event split the Community with hundreds of families adhering to their

belief in Sevy. This turmoil coupled with an economic crisis forced, finally, the centralization of

the administration of the Community (circa 1680) under the leadership of a single council

comprised of three Rabbis and seven secular members.

The stagnation will last up to around the middle of the 19th century. The Community, and the city

as a whole, will emerge from this lethargy and hibernation to its Renaissance around that time. The

Industrial Revolution, European Enlightenment, as well as the new socio-political conditions

prevailing in the Ottoman territories are in part responsible for the reversing of the trend and the

10

ushering of the new «modern» environment . From 1871 onwards the railroad will connect

Thessaloniki with North West Europe and Constantinople to the East. Modern western industrial

products make their appearance, further invigorating, via commerce, the interaction of the local

distinct groups of the population. The main groups that give the city is multicultural and

multiethnic character may be distinguished either linguistically, or by religious origin, or by

geographic origin. We find Greek Orthodox Christian Greeks [by ethnicity and origin] speaking

Greek, Muslims speaking Turkish and mainly of Ottoman origin and, finally, Jews, overwhelmingly

11

Sephardic speaking Ladino with their unique customs . We even find the Donme. The Ottoman

Empire had granted some privileges to its subjects of non Ottoman origin not out of kindness, but as

a means to keep then subjugated and second class, and heavily dependent on an intermediate

stratum of Turkish civil servants for their dealings with the central administration. This was not a

melting pot, and, even though this arrangement served the needs of the High Porte, it foreboded bad

omens.

The city boasted a number of very wealthy Jewish families amidst a majority who were daily bread

earners, living a hand to mouth existence, albeit while retaining their centuries old customs, their

language and traditions.

Thus next to the dozens of new schools created by the Community, the prominent factories and

wholesale and retail shops named after their Jewish owners, the Community also maintained social

welfare institutions in order to assist and support deprived, destitute and / or sick members. There

existed orphanages, health care facilities, and old age home.

Many newspapers circulated in Judeo Espagnol {Jewish–Judeo Spanish or Ladino} and in French.

Due to the presence of the Alliance Israélite Universelle { http://www.aiu.org }, French teaching

and schooling became available. Even a Socialist Workers Federation was created in 1909,

12 13 14 15 16 17 18

La «Federación»

.

The dawn of the year 1912 finds a Community, Sephardic to its core, with elements of

cosmopolitanism among its elite. It is also interesting to point out that during the previous year

1911, David Ben Gurion came to and resided in the city in order to attend the Ottoman Civil

Servant Preparatory School “Idadié”, because, at the time, Palestine was still under Ottoman rule.

Greek Thessaloniki

Year 1912 is a demarcation point of the second period of Jewish Thessaloniki (1492 – 1941). The

outcome of the Balkan wars finds the Modern Greek State, Hellas, victorious against the Ottoman

19

Turks and Thessaloniki in its fold . The incorporation of Thessaloniki in the Greek State had the

following immediate consequences: First, the overwhelming [near total] majority of the inhabitants

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 4 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

of Jewish religious origin became Greek citizens. Second, Thessaloniki became a border city of a

Nation – State in lieu of its previous position up to then, that of a major urban center with a sea port

in the crossroads of a vast hinterland of a multinational Empire. This fact had long lasting

economic and, subsequently, social and demographic repercussions.

The impact and importance of Jewish inhabitants becoming instantly Greek citizens of the Greek –

Hellenic State, requires more subtle analysis and is of paramount importance even today. I beg for

your forgiveness as, if only for a few moments, I will be instructional in my presentation: Before

1912, the population was comprised of Jews (religious and linguistic distinction), Muslims (Turks

and others), and Greeks identified as both a solid linguistic (Greek) and religious (Greek – Eastern

Orthodox Christian) group augmented with the fact of the uninterrupted presence for millennia in

the Geographic region. All were nominally subjects of the Sultan, albeit the non–Muslim ones of

20

lower status . Now Greece is a modern state with a Constitution guaranteeing equality for all its

Citizens. Thus, in one instance, a Greek may be Christian, Muslim, Jewish or whatever. In Greek

Grammar, like in the English one, the adjective precedes the noun that it defines or characterizes.

Therefore, from 1912 onwards, the correct form to use when we refer to the Jewish inhabitants of

the State of Greece who are Greek Citizens is Jewish Greeks and not Greek Jews. If it is not a case

of «political» correctness, well it is a case of correct grammar {syntax} and, even, Constitutional

21 22 23 24

correctness (and mandated by both its spirit and letter!)

. Therefore, when we refer to

non–Jews we should be using the terms of non – Jewish Greeks and neither plain Greeks nor plain

Christians. We should keep in mind that although, during the inter–war years, the post World War I

creation of many Nation–States exacerbated the problems of the minorities inside their respective

25 26

national borders

, this did hold true for Greece.

Greece embarked, understandably and as expected, on a path of Hellenization of the newly acquired

27

territory and, especially of Thessaloniki with its large non–Christian Greek population . The

process accelerated right after the Asia Minor Catastrophe and the subsequent population exchange

on a religious basis between Greece and Turkey [⇒ the defeat of Greece by Turkey in the Coastal

Region of Asia Minor that included Smyrna–Izmir in 1922. Greece was awarded jurisdiction of this

28

area, inhabited for millennia by Ethnic Greeks, following Turkey’s defeat in the First World War]

29 30 31

. {Here we meet again the Donme who, even though they were neither bona fide Muslims

nor considered themselves to be so, for the Greek State they were considered as such (i.e. Muslims)

and thus were expelled or «exchanged» along with the rest of the Muslims [excluding those in

Thrace] for the ethnic, linguistically and religiously, Greeks or Ionians of Asia Minor [excluding

those in Constantinople [Istanbul] and the Islands of Imvros and Tenedos]}.

Hellenization, vis–à–vis the Jewish inhabitant, entailed compulsory education in the official

language, i.e. Greek, compulsory military service, closing of the stores on Sunday instead of

Saturday [Shabbat] and, in general, a gradual inroad of the Christian Greek element to

predominance in almost all spheres of activity, especially economic. This trend accelerated when

the population imbalance became even more pronounced in favor of non–Jewish Greeks, after the

influx of Asia Minor refugees.

For a Nation – State with a population that was, at the time – circa late 1920’s – more than 96%

nominally composed of Christian Orthodox AND Greek speaking inhabitants, to manage to

incorporate and accommodate the Jewish minority in the fiber of the State web, without any

significant prejudice and xenophobia and with a total absence of discrimination or any outward

manifestation of discriminatory attitude, is in itself both remarkable and commendable. The

Modern Greek State had incorporated in its Constitution, from the beginning, all those principles

that guaranteed equal rights and equal treatment. Official State or Religious {Greek Orthodox

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 5 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

32

Church} anti–Judaism was both nonexistent and alien by contrast with, for example, Romania .

33 34

However, isolated individual manifestations of anti–Semitism did occur and are still occurring

.

Hellenization of the Jewish population had the beneficial effect (intended or not intended) of

turning second class subjects of the Ottoman Empire into full-fledged and full-righted citizens of a

Modern State. If the German annihilation had not taken place, who knows what the vibrancy of this

populous Community would have been today for the benefit of both, itself and the whole nation.

Maybe with the use of mathematical tools and simulation algorithms we might come up with a hint

35

of what would have been if .

Unfortunately the Hellenization process could only be applied to the new generation(s) of the time.

At the eve of the Second World War the majority of the Community members had only a

rudimentary knowledge of Greek. Therefore their Constitutional Greekness was not matched with

36

the linguistic requisite, that of the fluent command of the official language . Thus they stood apart

from the rest of the population in two obvious ways, first by their linguistic and cultural difference

and, second, by their sheer number. This set of distinctive defining characteristics was unique to

this Community. No other Jewish Greek Community matched them.

The inter–war years with the whole world in financial and political turmoil and Greece, with a

sudden population increase of almost 1500000 human beings, one fourth of the previous total,

struggling to absorb them and come to grips with the new social reality, were not conductive to the

welfare of the Community. The Jewish population was still reeling from the devastating effects of

the 1917 fire that destroyed many Jewish neighborhoods and burned synagogues. Many emigrated

37 38

for economic reasons, others due to isolated anti–Semitic acts e.g. the Campbell incident

.

Furthermore, the mandate of the Constitution [i.e. all Greeks are equal] was incapable, and never

meant, to force the acceptance and consideration of the Jews by non–Jews not as identical equals

but as equals. This is a fine distinction and the State did not help either with its misguided,

injudicious and shortsighted decision to segregate the Jewish voters from the Christians ones in

39

40

separate polling–stations, an act blatantly unconstitutional . This was a Community in transition .

The eve of the Second World War finds Thessaloniki with a Jewish population of around 55000

41

souls, a bit more than a fifth of the total population (See Figure 1). At its religious helm is a non–

42

Greek and non–Sephardic Chief Rabbi , the German born and educated Dr. Tzevi (Zwi, Cevy,

Zevi) Koretz. The Jewish Cemetery is a thorn in the plans of urban renewal and sprawl of this city

whose original centuries old character has changed irrevocably by the settlement of the refugees. If

we exclude the Jewish Greeks, the City is now totally homogenized in comparison with its previous

multi–ethnic and multi–cultural image.

Italy declares war on Greece on October 28, 1940 and fighting erupts on the Albanian front. Greece

is victorious and thousands of Jewish Greek conscripts and officers battle valiantly alongside their

43

non–Jewish (Christian) fellow Greeks . However, on April 6, 1941 Germany invades Greece from

the North. After fierce battles, they occupy the whole country. These events effectively conclude

the fascinating narrative of the two millennia Jewish Thessaloniki, bode a taste of the upcoming

tumultuous upheaval of the Community, and mark the end of the second period in the History of

Jewish Thessaloniki. The declared aim of the Occupier, if only thinly veiled, was the eventual

annihilation of the Jews, an event in World History that will come to be known as the Holocaust,

the Genocide of the European Jews. In less than three years time Jewish Thessaloniki will cease to

exist as such.

The Holocaust of Jewish Thessaloniki

C. From April 9, 1941 to October 30, 1944 – German Occupation

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 6 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Thus April 9, 1941 dawns and brings along the German occupier. This momentous event ushers the

Community, brusquely, to the third time period of its history –the history of the Holocaust of the

Jews of Thessaloniki– April 9, 1941 to May 8, 1945. A priori it should be noted here that the

period of German Occupation [more precisely of regions occupied by either the Germans, or

Italians, or Bulgarians] is characterized by extreme hardship and famine for the whole population,

Jewish and non-Jewish alike. Also the events that took place and the procedures applied for the

purpose of exterminating the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki were repeated at a later date, with

insignificant variations, for the annihilation of all other Jewish Communities in the rest of Greece.

What makes Thessaloniki stand apart is the fact of its sheer numerical strength and that it was the

first Community in Greece to experience the consequences of the implementation of the Endlösung

44

[Final Solution] . Events and ideas that shaped European Anti-Semitism and its subsequent

45 46

Genocidal strain in the 19th and the first half of the 20th centuries

may have been foreign to

mainstream Greece, but that fact did not impede the perpetrators to proceed with their murderous

plans.

Figure 1: Number of Jews in Thessaloniki as presented in the

“Final Report on the Activity of the Rosenberg Special Assignment Detachment in Greece”

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 7 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Upon their arrival, the Germans imprisoned many notables and arrested the Chief Rabbi Dr. Koretz

who was sent to and incarcerated in a Concentration Camp near Vienna. They appointed a new

Communal Council headed by Sabbetai “Saby” Saltiel as President of the Community, a man of

limited abilities but boundless ambition. For a span of almost 15 months nothing «major»

happened i.e. life threatening or total hardship and complete destitution like the one that was taking

place in the Warsaw Ghetto. Certainly the Jewish Press was silenced and Communal and private

book collections were plundered and confiscated by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg

Kommando [Special Assignment Detachment] along with all religious items of great historical

47

value . In addition, the German occupiers proceeded in outright plundering and pilfering of all

merchandize in stores of Jewish ownership and expropriated the best houses for their use. Thus, all

these actions and measures created the conditions for penury and destitution for a large part of the

Jewish population.

This period of relative «calm» and «normalcy» is shattered by an announcement of the German

Authorities, published in the newspaper «Apogevmatini» {Afternoon} edited by a collaborator,

calling all adult male Jews in the age group 18 to 45 years old to appear (assemble) for registration

at Plateia Eleftherias {Liberty Square} on Saturday, July 11, 1942 [The goal was to register the pool

48

of available men for forced–labor work]. The picture that follows says it all (Figure 2) . Nine

thousand [9000] adults gather in the square. The Germans did not allow them to cover their heads

or drink water in the sweltering heat, made them stand for hours under the blazing and scorching

sun, and some Germans even forced many to perform calisthenics! This was the first major omen

of worse things to come.

Sam Rouben

Plateia Eleftherias–Liberty Square, Saturday, July 11, 1942

Figure 2. The first person from the right, the one wearing eye glasses and standing

in front of the German soldier, is the late Sam Rouben from Oakland, California.

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 8 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 3: Check #2 of Drachmas 134,000,000 in part payment of the ransom.

This is the second of seven checks and it is signed by President of the JCT (Oct 29, 1942)

Sabbetai Saltiel. It was countersigned by Max Merten as Head of the Administration &

Economic Section {Abteilung} of the Thessaloniki – Aegean Command.

The check was transferred to the Reich Accounting Office on November 4, 1942 and

deposited and paid in full at the Bank of Greece the same day.

After the completion of registration many were conscripted for forced labor in various parts of the

Country. Hard labor, harsh conditions and insufficient food coupled with the fact that most were

already not in best of health or used to hard manual labor led to an accelerating attrition of the ranks

by death and many falling severely ill [it should be remembered that general famine was rampant

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 9 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

among the general population and in particular the Jewish one]. This deplorable situation forced the

Community to seek negotiations with the German authority as represented at the time by Dr. Max

Merten, Civilian War Advisor to the Thessaloniki–Aegean Command. The negotiations lead to an

agreement where the Community agrees to pay a huge ransom [2,500,000,000 drachmas–around

60,000,000 in current US$] in order to extricate its members from further compulsory onerous

forced labor. The following figure shows the front side of a Cashier’s check payable to the order of

the German Command [Befehlshaber] with a sum of 134,000,000 drachmas, from the Jewish

Community of Thessaloniki, signed by President Saltiel and dated October 29, 1942. The back side

shows the signature of Max Merten and the official seal as well as the Bank of Greece stamp as

49 50

(Figure 3). This check is the 2nd one out of a total of

PAID. The date is November 4, 1942

seven. This set of documents touches on another issue of the Holocaust of the Jews of Thessaloniki

specifically that of the financial audit of the money, fortunes etc that was involved. Forensic and

sleuth financial investigative methods most probably will have to be called upon for the research.

This topic is beyond the scope of this presentation.

In the meantime Rabbi Koretz was released from custody during January 1942 and returned to

Thessaloniki where he regained his post as Chief Rabbi. During this period Dr. Pohl of the

Rosenberg Special Assignment Detachment continues the plundering of archives, libraries and

collections of Judaica both in Thessaloniki and the in the nearby towns with sizable Jewish presence

51 52

and collections. He sends everything to Germany

. The Soviets will subsequently ship all the

archives to Moscow where they still remain. Dr. Pohl’s «punishment» after the war will be a year

and a half (May 1945 to October 1946) internment by the US forces . . . .

After the July 11, 1942 Platia Eleftherias event, the collaborationist local press {newspapers

APOGEVMATINI and NEA EVROPI [New Europe]} multiply in frequency of appearance and

augment in hate theirs editorials, articles and propaganda concerning the Jews. Along with the

ransom, during the end of the year 1942 and continuing in 1943, the German occupier accelerates

the expropriations, requisitions and seizures of all kinds of valuable merchandise form Jewish

owned stores. The usual stratagem is to simultaneously incarcerate the owner(s) for imaginary

infractions. As for paper and cardboard, both very precious and hard to find commodities and

useful for propaganda purposes {newspaper printing, flyers, journals etc.}, they created a new

corporation bearing the grandiose title of the German–Greek Paper Industry [Deutsch–Griechisch

Papier Industrie] whose inventory was, simply, the sum–total of all the paper collected [«stolen»]

from all Jewish print shops and warehouses. This «Industry» worked hand in hand with the

German Propaganda office in allocating paper to various individuals and entities, in whatever

quantity and price. That way they had full control on all printed matter and made life difficult for

resistance printing.

The year–end brings a calamity of another sort, that of the destruction of the centuries old Jewish

Cemetery with more than 500,000 tombs, most of them of priceless historical value. The Governor

General of Macedonia of the time with the assistance of the German Occupier succeeded in

completely obliterating anything that might remind someone what existed there for centuries. The

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki has been built on these holy grounds. This is both a very sad

53

and shameful chapter in the history of the City as a whole . December 1942 also brings a change

in the Community administration: The Germans demote Saltiel and put Dr. Koretz in the helm of

the Community. Thus Koretz assumes both posts, that of the President of the Community while

retaining the post of chief religious leader that of Chief Rabbi. His fluency [native tongue] in

German facilitates his deliberations with his German masters. He is their persona grata and, having

experienced firsthand the “care” of the SS and the Gestapo in Vienna, is eager to oblige.

The day of reckoning is near. On the military war front things are not going very well for Germany

and the other Axis powers. The New Year 1943 finds General Paulus’ 6th Army encircled in the

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 10 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

«Cauldron» [Kessel] of Stalingrad. Field Marshal Paulus surrenders to the Soviet Armed Forces on

54 55

February 1st, 1943

. This marks a turning point on two fronts: A turn for the worse for the Axis

powers with defeat starting to loom very probable in the not so distant future and an intensification

of Germany’s War against the Jews where each single day that the German Reich remains

56

undefeated has as outcome the addition of thousands of victims to the grand total .

Thessaloniki now has the dubious distinction of being the first Community destined for annihilation

right after the military defeat at Stalingrad. The machinery of Death is put into gear and high

action. The events follow one another in rapid succession, culminating, as we shall see, in the near

total extinction of Jewish presence in Thessaloniki and the extermination of more than 90% of its

members.

On Saturday, February 6, 1943, arrives the Special Assignment Detachment of the Reich Security

Service in charge of the «Jewish» Department. This is headed by Dieter Wisliceny,

SS Hauptsturmführer [rank equivalent to that of Captain in the US Army], and his subordinate

(seniority wise) Alois Brunner, also an SS Hauptsturmführer. (Initially in their careers Adolf

Eichmann was subordinate to Wisliceny. However, Eichmann was more zealous and hard working

and, at some point in the course of time, outranked Wisliceny. They were always close and

Wisliceny christened Eichmann’s third son giving him the name Dieter). Thus Adolf Eichmann, the

technocrat–bureaucrat genocidist par excellence, «honored» Thessaloniki with two of his best and

most competent operatives.

It is a bitter irony to state that Eichmann during his interrogation by Israeli (Berlin Born) Police

Captain Avner Less (1960), and the infamous Dr. Max Merten in his testimonial affidavit for the

Eichmann trial (1961), both reproach and blame Wisliceny for taking the initiative and acting

outside orders! This a paradigm of a charade where the superiors blame the inferiors for performing

better that ordered to! The circle of recriminations among the former Kameraden started with

57 58 59

Wisliceny’s testimony, in 1946, during the Nurnberg Trials

. In that Wisliceny blames the

others, the same way as Eichmann attempts to persuade the Court and stands fast during his own

trial. The facts that emerge are that ALL of them worked diligently to bring their task to «fruition“.

A document that I will present for the FIRST time proves that the initiatives that Wisliceny took

had as sole purpose the expediting of the “resettlement to the East” process.

The chain of events starts with the call–order to Koretz to confer with the SD Detachment. This

takes place on Monday, February 8, 1943 and, immediately, he is handed the first order signed by

Max Merten that introduces the German Nurnberg Racial Laws effective almost immediately. The

60

mockery of it is that the order was antedated to February 6 . The order decreed that Jews should

be distinguished as such, i.e. marked with a distinctive sign, and that they should concentrate at and

live in specific areas [Ghettos].

Wisliceny is empowered to enforce these directives and issues his implementation orders. These

orders command that all Jewish shops should be marked as such, and, the distinctive mark for all

Jewish Greek (NOT non–Greeks) persons aged more than 5 years should be the Yellow Star of

David {the six pointed star}. It should be made out of cloth and sewn on garments and overcoats.

And here comes the damning document in living color (see Figure 4): Wisliceny’s order stipulated

that, along with the garment distinctive mark, all Jewish Greeks should be issued a Community

Identity Card numbered sequentially and identifying the holder as Jewish. The same number

appearing on the ID {Ausweis} should also be stamped on the cloth stars. Below is the

Authorization document for the release of cardboard {Karton = carton} for the printing production

of 55,000 Identity Cards printed on carton {Ausweise (Karton)} for the Jewish Community of

Thessaloniki with Index–Identification number 2788 ab {Kennziffer Nr} and, the release was

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 11 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

further authorized, on top of the regular Officer of the German Propaganda Office, by non–other

61

than Wisliceny! (Figure 4) . The print shop was the Imprimerie David Gattegno.

This document substantiates the fact that 55,000 Identity Cards were printed. Considering that at

most 1,000 would be misprinted and destroyed plus the fact that infants were exempt, we have a

near certain indication of the numerical strength of the Community on the eve of its obliteration.

This number is also corroborated by the population table in the Rosenberg Report as shown on

Figure 1. The tragedy is unfolding but, unlike Antiquity, we all know that no redemption – no

Catharsis – will follow.

The Propaganda Office directives stipulated that a surcharge [Pflichtgebühr] of 10% should be

levied for the services of the Propaganda Office. That 10% was arbitrarily augmented to 50% for

works printed for the Jewish Community (!) [Further figures are shown during the presentation].

However, Wisliceny pulls rank and takes the initiative to waive the obligatory surcharge. What a

bighearted gesture! In order to expedite the hideous process he waived part of the cost that his

victims had to assume in order to be murdered!

The Index–Identification number had to appear on all printed matter. Since the ID cards were the

second – β) – item authorized, the following identification mark had to be clearly printed on the

IDs: Gatt. Gen. No. 2788 B. Figure 5 shows a Personal Identification Card issued by the Jewish

Community in compliance with Wisliceny’s order of February 12, 1943. The Index–Identification

Number is easily discernible on the Card {the Card belongs to the Jewish Museum of

Thessaloniki}.

The SD authorities, along with the civilian advisor Max Merten continued to shower the bewildered

and, most of all, frightened and alarmed population with further requirements to meet in order to

keep them busy and disoriented. One of those was the wealth declaration, including filling up

special forms with minute details such as full description (and value) of kitchen utensils and cutlery.

Here is facsimile copy of such a declaration form [during presentation] and Figure 6 shows the

original instructions in Judeo–Spanish of how to fill the declaration. The flyer forewarns those

obligated to fill the forms that they should be very diligent, otherwise they would risk severe

punishment by the German Authority!

Actually this document, composed in Judeo–Spanish with Latin characters, constitutes also proof

that, for at least some «official» Community announcements to its members, Greek was not used.

Therefore, we can only deduce that, even at the beginning of 1943, the spoken and understood

language among the majority of the Jews of Thessaloniki was Ladino.

In conclusion, all this paperwork for nothing, besides its sole purpose in registering and identifying

the Jews as such and keeping them continuously on edge, proves that the German perpetrators

relished Bureaucracy along with Murder. It might have been that Bureaucracy served also as a

psychological shield for disguising their horrid task as a «simple» implementation of a predefined

plan of «resettlement». Maybe a postmortem forensic psychoanalysis of the perpetrators’ souls

62

might reveal something !

These events, following one another in rapid succession, culminate in the announcement by the

German Authorities and subsequently by Chief Rabbi Koretz that an order has been issued that all

the members of the Community will be deported and resettled in the District of Krakow in Poland.

This is the beginning of the end for the great Sephardic Community, the «Mother in Israel–Madre

en Israel» as it was known. The destiny of all has been decided. The malevolent intentions and

deeds of the Reich to the day did not leave any niche for hope . . . .

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 12 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 4: Authorization for the Carton release for the impression of 55,000 Identity Cards

The Document is dated February 17, 1943, over signed by Wisliceny

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 13 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Gatt is written in the lower left corner [Gatt stands for Gattegno] plus the Number

Figure 5: Personal Identification Card issued by the Jewish Community in compliance

with Wisliceny’s order of February 12, 1943. Rabbi Koretz signs the Card as President.

However agonizing and excruciating the evolving drama of the Jews of Thessaloniki, our

perspective would be incomplete if we did not acquire a general overview of the larger image and

happenings in the whole of occupied Greece during that period. The consequences of the

Occupation were especially severe for Greece, a net importer of foodstuffs. If the British hadn’t

lifted the naval blockade for relief ships of the International Red Cross and other Aid Organizations,

especially after the severe famine of the first year and a half, there wouldn’t have been any Greeks

63

left and no Hellenic Nation. Reprisals for acts of resistance were also harsh. .

Deportations – Concentration Camps – Rescuers – Resistance –

Jews of Spanish Nationality

Deportations

The first convoy of Jewish Greeks departs ostensibly for Krakow on March 15, 1943. The final

destination is the Concentration and Death Camp complex of Auschwitz – Birkenau near the Polish

town of Oswiecim. All deportees are allowed to carry only a certain amount of Polish Zloty with

them, ostensibly for use in Krakow Poland. These Zloty they «buy» in exchange for drachmas.

They are strictly forbidden to carry with them precious stones, gold and/or foreign or Greek paper

money. They are required, under penalty of severe punishment, to deposit all these valuables at the

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 14 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Ghetto offices before they leave (What happened to all this wealth?). Witness accounts, among

them my father’s, describe in detail their ordeal in the cattle cars, hermetically sealed for many days

64 65 66 67 68

during their long journey to extinction

. Consecutive convoys follow and, in the space

of two months, the city becomes practically Judenrein. Desperate attempts to approach the German

authorities, by Metropolitan Genadios and the occupation Greek Prime Minister Rallis, and to

intervene on behalf of their persecuted fellow citizens had no effect whatsoever. This intervention

«cost» Chief Rabbi Koretz his job as President since it infuriated his German masters. He was

relieved from his duties and incarcerated in the Baron Hirsch ghetto, the springboard of the

69

deportations and the liquidation of the Community . Table 1 shows the arrival of the Convoys

according to the Auschwitz Camp records.

Very few Jews, especially those with a command of the Greek language, managed to escape and

hide. Unfortunately even quite a few of those, against the best advise of their non–Jewish

acquaintances and friends and their own gut feeling, decided to follow their elders to the unknown

hopping for the best. Some Christian Greek families sheltered others at the penalty of death if

discovered. Unfortunately other bystanders saw an opportunity to share on the spoils and pilfering

70 71

.

of property and assets left behind

This page of History, the daily events of the tumultuous period before and during deportations, has

yet to be researched. The best approach is to state the facts and present archival material and

documents. The researcher has to try to resuscitate the minute details of events and daily

72

happenings of the era and, of paramount importance, to convey the intensity of it all . Very little

73

research has been done (to the best of my knowledge) on Comparative Holocaust and on the

effectiveness of the Bureaucracy of Genocide at the various countries where the «Final Solution»

74

was implemented and carried out to the end (what Hannah Arendt described very aptly as The

75

Banality of Evil ). The documented presentation of the Holocaust in the various European

76

77

Countries as found in Dawidowicz, in Raoul Hilberg and, pictorially, in Schoenberner and in

78

Milton , describe and depict, in a rather concise manner, how the annihilation process was carried

out in each country. Even from those we surmise that the implementation procedures, including the

bureaucratic ones, differed from country to country and that many were improvised in particular

localities (e.g. the process steps –NOT the end goal– were different in Athens as compared with

those in Thessaloniki). A fresh study of the deportations and subsequent annihilation of the Jews of

Greece and especially of the Jews of Thessaloniki is presented in the book by Margaritis

79

“Undesirable fellow–countrymen, Tsamides–Jews” .

Concentration and Death Camps

Returning to the doomed souls who travel north in the trains of death, we should point out a few

facts: First, the Jewish Greeks had another dubious honor, that of being located the farthest away

from the Death Camps [map during presentation]. This had as a result a very long journey in

abhorring conditions that lasted for many days and claimed the lives of many even before arrival at

the camp. Second, unknown to all at the time, those selected for slave labor had to confront the

hardships for two full years in order to survive the War. Lastly, they knew no German, Yiddish,

Polish or other «Camp» languages, a fact that hindered communication. In addition, they were not

used to the extreme climate of the region, especially the bitter ice–cold winters so foreign in

Mediterranean Countries.

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 15 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 6: Instructions on how to fill the wealth declaration forms, March 1, 1943

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 16 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Table 1

Official records of the total of Thessaloniki Jews sent [deported] to the

German Concentration & Extermination Camps Auschwitz – Birkenau

Records from the Archives of the Concentration Camps Auschwitz – Birkenau

Convoy

1st

2nd

3rd

4th

5th

6th

7th

8th

9th

10th

11th

12th

13th

14th

15th

16th

17th

18th

19th

Total

Date of Arrival

20/3/1943

23/3/1943

25/3/1943

30/3/1943

3/4/1943

9/4/1943

10/4/1943

13/4/1943

17/4/1943

18/4/1943

22/4/1943

26/4/1943

28/4/1943

4/5/1943

7/5/1943

8/5/1943

16/5/1943

8/6/1943

18/8/1943

Total

•• 2/8/1943

of Displaced Persons:

Persons

2,800

2,800

1,901

2,501

2,800

2,500

2,750

2,800

3,000

2,501

2,800

2,400

3,070

2,930

1,000

2,500

4,500

880

1,800

48,233

• 441

48,674

• Destination: Bergen–Belsen Concentration Camp

•• Date of Departure

In 1945 the Jews who returned numbered 1,950

Percentage of losses greater than 96%

Note: Some convoys may havepicked up more people after Thessaloniki

All the convoys that left Thessaloniki had Auschwitz–Birkenau as their final destination except one

that left in August 2, 1943 with 367 Spanish Jews, permanent residents of Thessaloniki, and a few

«notables» (among them Rabbi Koretz) for the Bergen–Belsen Camp (This Camp is situated near

the cities of Hannover and Celle in Germany. We will present the saga and fate of those Jews

substantiated with documentary evidence below). Approximately 44000 Jews were deported from

the Hirsch Transit Camp in Thessaloniki. Two thousand five hundred more Jews from surrounding

Communities were also deported bringing the total to 46500 souls. The fate of the overwhelming

majority upon arrival is well known: After the selection process to separate the fit for slave labor

(and those destined for «medical» experiments) from the rest, the last ones, comprising the majority

80 81 82 83

of the transport, were immediately gassed and subsequently burned in the Crematoria

.

Sevillias, Menashe and Handali give vivid and detailed descriptions of the ordeal, all of them being

victims and eyewitnesses who survived to tell their story. Sevillias was arrested in Athens in March

1944 and deported to Auschwitz–Birkenau. His testimony presents the sequence of events

pertaining to the entrapment and subsequent deportation of the Jews in Athens during Spring 1944.

The opus by Michael Molho describes in detail both the deportations from all parts of Greece as

well as the travails of Jewish Greek slave inmates at the Concentration Camps. It also describes the

horrible medical experiments performed by the German Camp «Physicians» using many Jews and

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 17 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Jewesses from Thessaloniki and the rest of Greece as guinea pigs. A Treatise from a researcher at

the (Polish) Auschwitz State Museum offers many details specifically about the Jewish Greeks at

84

Auschwitz . The Chronika 2006 commemorative issue on the Holocaust of the Jewish Greeks

85

includes an English supplement . There are quite a few other sources; however, each one only

86 87 88

adds a few more details to the main facts

. A commemorative volume on the Holocaust of all

Jewish Communities of Greece was presented at a moving event on Capitol Hill organized by the

89

Embassy of Greece on June 21, 2006 . Another general reference (of many) on the subject of the

90

World War II Holocaust of Roma, Jews & others is . As for myself, I was able to extricate

information from my father Leon, Konzentrationslager [KL]–Auschwitz Nr. 118633 inmate,

liberated on January 27, 1945.

Note: The early liquidation of Polish Ghettos and the deportation of Jewish Poles to

Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor Death Camps had as sole purpose the immediate

91

assassination – extermination of ALL upon arrival . It was with the development,

growth and enlargement of the Auschwitz – Birkenau Camp Complex plus the

attached satellite industrial establishments that the German Reich and the SS realized

the value of slave labor and selections were instituted to that effect. This is one

reason why so few Jewish Poles survived {⇒ all destined to extermination} by

contrast with Camp «latecomers» (Spring – Summer 1944) Jewish Hungarians

{⇒ combination selection for slave labor or immediate gassing and cremation}.

Those spared immediate death had to endure the hardship(s) of their incarceration for

a shorter duration (less than half) compared to the one the Thessaloniki Jews had to

92 93 94

.

(endure) in order to survive the war

It is interesting to note that both The Times (London) and The New York Times did publish

the news pertaining to the fate of the Jews of Thessaloniki during the War. First a Times article in

95

May 1943 described in detail how the Jews were deported from Thessaloniki . Then a February

96

1944 NYT article reports that “Jews in Salonika Virtually Wiped Out” . A follow–up article,

97

again in The NYT reports that “48,000 Greek Jews are sent to Poland” . Finally, a November

98

1944 NYT article reports that “Most Salonika Jews Killed” . It is only logical to conclude from

the above information that there is NO excuse for anyone living in neutral countries such as

Sweden, Switzerland, Portugal, Spain, and Turkey to claim that he, she or they had no idea

whatsoever on what was going on. . . .

Rescuers

The History of the Holocaust of the Jews of Greece would be incomplete if no mention was made

about the gallant efforts of Christians to save their Jewish Brethren. After all I owe my existence to

the rescue of my mother (in Athens) by her women saviors Zoe Morou–Folerou and Danae

Kadoglou–Pavlidou, declared Righteous by Yad Vashem in 1999. Many Christian Greeks

sheltered whole Jewish families or helped them to escape to Athens or to the surrounding

countryside. However, the family bond and loyalty being strong, many young persons although

forewarned and offered either shelter or escape, chose to accompany their elders to . . . Krakow.

Archbishop Papandreou Damaskinos h, Archbishop of Athens and the whole of

Greece, is universally recognized for his representation to the German Authorities in March 1943

and for his Sermon cum Proclamation urging [Christian] Greeks to shelter Jews. Among other

things he stated that «Our Holy Religion does not recognize any distinction of superiority or

inferiority based on race or religion». These are words with everlasting universal appeal.

Archbishop Damaskinos was recognized and honored for his efforts and deeds on behalf of his

fellow Jewish countrymen and of being instrumental in rescuing and saving many, especially in

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 18 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

99 100

Athens

. While the War was still raging, especially the one against the Jews, the Palestine

101

Labor Federation thanked the Greek People for aid to Jews .

A bright light in this gloom is the miracle of the island of Zakinthos where ALL its Jewish

inhabitants were spared thanks to the efforts of the Metropolitan and the Mayor (see Michael

Molho). However, this was the exemption to the rule. Occupation coupled with the constant threat

of capital punishment in case someone aided Jews played a major role in one’s decision to help or

not, spontaneously or after thought, fellow humans. It is an undisputed and document fact that

Athens with a Jewish population only a tiny fraction of that of Thessaloniki (one fiftieth 1/50!) had

a disproportionate number of Christian rescuers and Jewish rescued. One reason might be that the

Community, being tiny, was dispersed and fully integrated with the rest of the population of the big

city. Furthermore, Jews in Athens were almost totally Hellenized (remember that Thessaloniki

became Greek only in 1912. The Greek people declared a Revolution against the

Ottomans on March 25, 1821 [Greek National Holiday]. The first National Assembly at

Epidaurus {Epidavros – Επίδαυρος} established the Hellenic State on January 1, 1822.

102 103

.) On the other

The first free areas included part of the Peloponnese and Athens

hand, the sheer number of Thessaloniki Jews, the older generation(s) inadequacy in fluent Greek,

and the natural tendency to congregate amongst themselves did not facilitate or promote the

integration with and dispersion in the rest of the population. This situation was not conductive to

forging friendships and acquaintances with the Christian fellow–countrymen or neighbors. The

non–Jewish population considered them, by and large unwittingly, as plainly Jews and not Greeks

or, at least, Jewish Greeks. This is evident even from official Greek Documents which address

104

them as Jewish fellow–citizens and reserve the term Greek people for the rest . The point is that,

even though NO offence whatsoever was intended, this prevailing attitude did not help the

105

(Christian) Greeks to feel–consider the (Jewish) Greeks as Greeks (no play of words intended)

106

.

Resistance

Last, but not least, many ask if there was Jewish resistance. First of all thousands of Jewish Greeks,

as we have seen, fought valiantly against the Italians and Germans alongside and together with their

Christian Greek fellow countrymen. Quite a few joined the Resistance. And the Sonderkommando

revolt at Birkenau was organized and lead by a Jewish Greek inmate, an officer of the Greek Army

caught in Janina (Ioannina) in 1944, the year that the Germans swept the rest of Greece for Jews to

deport. This topic is still being researched and the interested reader should consult the

107 108 109 110 111

.

References

The near total annihilation of the Jewish population of Thessaloniki and, likewise, of the rest of

112

Greece brings this chapter of the Jewish History to a forced and abrupt termination . The

liberation of Thessaloniki, when the last German soldier leaves the city on October 30, 1944, marks

the beginning of the current phase of the Jewish presence, albeit drastically reduced. Time will

show that numeric inferiority might be offset by other characteristics. The evidence till now is

113

encouraging!

Before we leave this tumultuous (and catalytic?) era for the Jewry of Thessaloniki and the whole of

Europe, we will sidestep and follow the fate of Jewish Spanish nationals of the city during the

period 1943 – 1945. This chapter is a paradigm of uprooting and upheaval, albeit with a happy

ending [⇒ survival] and full circle back home to Greece [⇒ to the roots] via Spain [⇒ where it all

originated centuries ago!].

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 19 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

The Spanish Jews of Thessaloniki

The Chronicle–Narrative of the Spanish Jews of Thessaloniki

A special group of Jewish inhabitants of Thessaloniki were the non–Greek nationals. The major

group was the Spanish nationals and then came the Italians. These were Spanish citizens but they

were not allowed to enter Spain automatically. They had to renew their Certificate of Nationality

each year. The Certificate was issued by the Spanish Consulate of Thessaloniki. As a group they

were exempt from the racial laws that were applied to their Jewish Greek coreligionists, i.e. they did

not have to wear the Yellow Star or live in the Ghetto. Spain was a neutral country albeit favorably

predisposed towards the German Reich and the Axis Powers. Spain had only a few years back

achieve relative calm with the end of the Civil War. General Franco was the Leader of the State

and the Monarchy was abolished. This was immediately manifested with the change of the Coat of

Arms that was printed on the front of the Certificate of Nationality (see Figure 7).

As long as Spain was both neutral and friendly towards Germany, Spanish Jews were relatively

safe. However, with the tempo of the sequence persecutions – deportations accelerating in 1943,

the German appetite for more Jews to destine for “Special Treatment [Sonderbehandlung]”

increased. Spain’s reluctance to accept large numbers of its undesirable non–resident citizens

risked to be construed by the Germans as a «carte blanche» to do as they please with the Jewish

Spanish nationals in its fold. Nevertheless, after much bureaucratic deliberation among the

pertinent German and Spanish Authorities, the Germans finally deported the Spanish nationals to

Bergen–Belsen [August 2, 1943] and housed them in separate barracks. After further deliberations

among the Spanish Government and the Germans they were finally freed and allowed to travel to

and enter Spain via France (all 367 of them). Their sojourn in Spain was brief, just a few months in

114

Barcelona, and then they were shipped to Casablanca on June 14, 1944 . With the assistance of

UNRRA they were sent to Palestine. They were finally able to return to Greece after August 9,

115 116

1945

.

We will attempt to visualize their Odyssey by retracing some instances of their lives these three

years (1943–1945). This is a virtual journey for us but a very real one for them fraught with rigor

and privation and, most of all, the threat of extermination hanging on top of their hands as long as

they were in the custody of the Reich. This we achieve by following the story David Jacob

Gattegno and Rachel Gattegno using as a temporal and location fixing compass a set of pertinent

archival documents:

The couple David Gattegno and Rachel Gattegno (born Frances) hails from a family that lived for

centuries in Thessaloniki. David Gattegno owns (owned) a Print Shop that specialized in quality

printing. They are both Spanish nationals, permanent residents of Thessaloniki. They renew their

Certificates of Nationality annually and the 1941 Certificate of David displays prominently the new

Franco era Coat of Arms (see Figure 7). The German Authorities stamp the Certificate with the

following word logo: “BESCHEINIGUNG DER SPANISCHER ANGEHÖRIGKEIT” i.e. Certificate of

Spanish Citizenship (see Figure 7a). Thus Spanish citizens are identified as such by the Occupation

Authorities and distinguished from the Jewish Greeks. They are exempt from the race

[«Nuremberg»] Laws which are being enforced upon their Greek national brethren starting mid

February 1943.

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 20 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 7: Front of the 1941 Certificate of Nationality of David Gattegno

The Certificate was issued at Thessaloniki by the Spanish Consulate

Figure 7a: Magnification of the German Stamp that adds the German equivalent

of the Document Title of Certificate of Spanish Citizenship

We now follow the itinerary of the Spanish Jews by «riding» the Passport of the Gattegnos

some other pertinent documents of the era as a virtual vehicle.

117

and

The Germans draw a list of all Spanish nationals of Jewish origin who belong to the Jewish

Community of Thessaloniki. The following Figure 9 shows part of the 12 pages 1943 German

118

document listing the Spanish Jews of Thessaloniki . I have included only the names of the

Gattegnos without loss of generality. Note that in the last column is written when their Spanish

Nationality ID was issued (Compare it with the above Figure 8). Also note the address given

(Hr. Smyrni 9). This is my actual business & home address (!) if new numbering is taken into

account [current number is 11].

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 21 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 8: Details of the 1941 Certificate of Nationality of David Gattegno [inside–back]

The Certificate was issued on July 8, 1941. It identifies David Gattegno as a printer

(The Germans has entered Thessaloniki on April 9 of the same year)

The Gattegnos, like the rest of Spanish nationals, are making preparations for the journey to the . . .

unknown. They apply for a husband–wife common Passport at the Spanish Legation in Athens.

Their Passport is signed by Consul Sebastian de Romero (whose name appears in the historiography

of the Spanish Jews of Thessaloniki and who will remain for some years as Consul after Liberation)

119

(Figure 10). The Gattegnos write a letter to Paul Frances , Rachel’s son from an earlier marriage,

who had managed to leave Greece earlier, describing to him their situation and predicament,

mentioning among other things that they were allowed to take with them 5000 Swiss Francs. The

120

letter is dated Thursday, May 27, 1943 .

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 22 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 9: German Legation Legal Advisor von Thadden’s letter accompanied with the

full list all Spanish Nationals of the «Jewish race» (sic) who belong to the

Jewish Community of Thessaloniki as of April 30, 1943. Bear in mind that by that date,

out of the total 19 convoys to Auscwitz–Birkenau, 13 had already left . . .

(Only the Gattegnos are included without loss of generality)

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 23 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 8: Page 1

The Passport was issued by the General Consulate of Spain in Greece

Figure 9

Page 2 The Passport was issued on May 25, 1943

Page 3 Personal Data of the Passport Holders

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 24 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Page 4

Page 5a

Page 5b

Figure 10

Signature by the Consul General of Spain, Sebastian de Romero,

May 25, 1943

Authorization–Permission by the Consulate General of Spain in Athens

for the Holders to enter Spain for one time only(!) from the border crossing

at Irun [opposite Hendaye France] (July 6, 1943)

Entrance Stamp in Spain (Port–Bou opposite Cerbère France and not

Irun), February 10, 1944 [note the 7 months period that has elapsed]

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 25 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Page 6

Page 6a

Page 7

Figure 11

Authorization–Permission from the Bank of Greece to export foreign

currency (2000 Swiss Francs or the equivalent in other foreign banknotes

[currencies]), June 7, 1943. The export permit is valid for 15 days

Second Entrance Stamp in Spain (Port–Bou), February 10, 1944

Authorization–Permission from the Bank of Greece to export foreign

currency (3000 Swiss Francs or the equivalent in other foreign banknotes

[currencies]), June 9, 1943. The export permit is valid for 15 days

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 26 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 12: Count List [Devisenzählung] of Foreign Currency, gold and jewelry belonging

to Jewish Spanish Nationals being deported to Bergen–Belsen seized–confiscated by the

German Authorities one day before the departure of the 19th Convoy (destination Bergen–

Belsen), July 31, 1943. The person responsible for collecting the valuables and completing

the List was Dieter Wisliceny. Note that according to the Authorization–Export

Permissions by the Bank of Greece (Passport Pages 6 & 7) David Gattegno was allowed to

take out a total of 5000 Swiss Francs with him . . .

121

(Without loss of generality I include only David Gattegno)

Wisliceny claims that David Gattegno deposited only 30 Swiss Francs while (as we know) he had

permission to carry and export up to 5000 Francs (Figure 11). The options are the following:

1

David Gattegno took only 30 Francs with him.

2

David Gattegno was carrying a larger sum but was able to conceal it despite the

threat of severe punishment if found.

3

Wisliceny, along with the rest of his detachment, profited from the loot and

reported altered tallies to the Reich Finanz [Finance] Authorities.

The most obvious correct answer to this multiple choice question is 3. So Wisliceny and the rest of

the perpetrators were not only extraordinary murderers but they were also common thieves [as in

crooks, bandits & robbers]! So much for the «High» principles of National Socialism, the

122 123

Herrenvolk and, last but not least, the Elite of the Elite, the SS!

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 27 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 13: A note, dated December 2, 1943, declares that the «Judenaktion» in

Thessaloniki resulted in the confiscation of 22300000 Drachmas, 40185 US Dollars and

55345 Swiss Francs, plus what they seized from the Jewish Spanish Nationals

There exists a «gap» in exit and entry Stamps: First of all they were hoarded on a train and

deported on August 2, 1944 so there were no «niceties» such as border stampings exiting Greece,

entering Yugoslavia, and then the Reich to Bergen–Belsen (remember Austria was the Reich

Province of Ostmark). Again there is no exit Stamps from the Reich or entry into a (fully)

Occupied France and dumped at the French–Spanish frontier at Cerbère (Figure 15) for

subsequent entry into Spain and final destination, there, Barcelona (Figures 10, 11, 14 & 15)

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 28 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Page 5 (stamp)

Page 6 (stamp)

Page 8

Page 8a

Page 8b

Page 9

Figure 14

Entrance Stamp in Spain (Port–Bou), February 10, 1944

Second Entrance Stamp in Spain (Port–Bou), February 10, 1944

Figure 15

Authorization by the Spanish Consulate General in Athens for the Pass Holders

to enter Spain without having to pay any custom duties or levies for the import

of their personal belongings due to the fact that they always resided abroad

[i.e. in Greece and not Spain] July 6, 1943

One orthogonal Spanish Stamp dated February 2, 1944 (?). A faint digit 3

after the digit 2 is discernible in magnification

A small round Stamp of the Customs of Port–Bou

French Exit Visa by the Vichy Police at the border town of Cerbère, Région de

Montpellier, opposite Spanish Port–Bou, February 10, 1944. Note the Vichy

Coat of Arms on the Stamp

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 29 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Page 10

Page 11

Figure 16

Spanish Stamp, April 4, 1944

Gratis Extension of the validity of the Passport at the Spanish Consulate

General in Palestine at Jerusalem, July 4, 1945

[Note the gap with no Exit or Entrance Stamps from Spain to Casablanca and

then on to Palestine, a time period of more than a year]

124

A New York Times article

The text follows:

dated February 17, 1944 reports that “365 Jews Reach Spain”.

MADRID, Feb. 16 (2P)—The Spanish Foreign Legion announced today that

365 Spanish-speaking Jews descended from those expelled from Spain by

Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand in 1492 had been brought to Spain after

negotiations with Berlin freed them from a German concentration camp at

Bergen Belsen. Thousands of these Spanish Jews lived in Salonika and

elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean. They speak a type of Spanish little

different from that spoken in the time of Isabella and Ferdinand. A note by

the Foreign Ministry said those repatriated expressed their unanimous

thanks and satisfaction for the Spanish Government's help in getting them

out of the German concentration camp.

November 14, 2006

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 30 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

Figure 17: Food Ration Card issued to the

Gattegnos in Barcelona

Figure 18b: The outside back cover of the

Passport was stamped with the note

“UNION OF POLISH INMATES”

(in Greek after the return)

Page 12

Inside Back Cover

November 14, 2006

Figure 18

Entrance Stamp to Greece and Stamp [Timbre] Consular Fees

levied at the Port of Piraeus on August 26, 1945 due the lack of

Greek Consular attestation [in Jerusalem]

Various Stamps, February, March & April 1944 [Barcelona Spain]

West Chester University of Pennsylvania

Paul Isaac Hagouel, hagouel@eecs.berkeley.edu

page 31 of 47

History of the Jews of Thessaloniki and the Holocaust

There exists another gap in exit and entry Stamps: No exit Stamp from Spain to Casablanca exists

and neither an entry Stamp to Palestine (at the time under the League of Nations British Mandate).

Figure 16 bears the extension of the validity of the Passport issued by the Consulate General of

Spain in Palestine and located in Jerusalem. Figure 17 shows a Food Ration Card issued to the