James L. Bruner, Columbia

advertisement

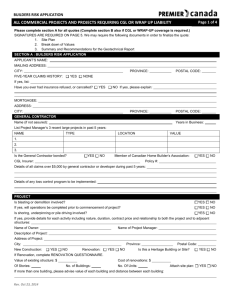

ALLOCATION OF DAMAGES AMONG CARRIERS IN CONSTRUCTION DEFECT CLAIMS James L. Bruner, Esq. Bruner Powell Robbins Wall & Mullins, LLC Columbia, SC I. An Allocation Example A GC built a 7-story condominium building in North Myrtle Beach. The pertinent facts concerning construction and the contractor’s insurance are: CGL/Excess Policy Anniversary Date: CGL Policy Form: Construction Began: Construction completed: CO Issued: January 1 ISO CG 00 01 07 98 June 1, 2000 October 31, 2001 November 30, 2001 Although the GC completed all of its work, the developer went broke and never paid the GC its final draw and retainage. The GC goes broke and closes its doors on December 31, 2005. During a storm in the fall of 2003, the homeowners notice water intrusion around windows and under the sliding glass doors on the unit balconies. They ask the GC to investigate and it does so. It attributes the water intrusion to the storm event and assures the homeowners that all is well. In the spring of 2004, the homeowners notice more water intrusion. Again, they notify the GC which investigates and tells the homeowners the water intrusion is due to lack of maintenance. The homeowners get a lawyer who, in turn, hires a consulting engineer to “inspect” the building in the summer of 2004. The PE’s inspection report is dated November 30, 2004 and recites numerous construction defects, deviations from the plans and building code violations some of which are allowing water into the building. The PE opines that the water has been entering the building and its walls since the windows, doors and walls were completed. 1 The lawyer obtains an estimate of costs to correct these deficiencies - $22,500,000. The lawyer sends the GC a copy of the inspection report and estimate and demands that it correct all of the deficiencies. The GC sends the demand letter to its insurance agent who places three CGL carriers and four excess carriers on notice. No response is sent to the demand letter. On April 1, 2005, the homeowners file suit against the GC in Horry County Circuit Court. The GC is defended by lawyers hired by CGL #3. CGL#3 has demanded that CGL#1 and #2 share in the defense costs. CGL #2 has agreed but CGL#1 has declined. The GC files third-party claims against virtually all of its subcontractors. The case is placed on the Multi-week Trial Docket and ordered to mediation in June 2007. At mediation, CGL#1, #2 and #3 and Excess #1 show up with coverage counsel. Here are their respective coverage periods and limits of liability: 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #3 $500,000 CSL A. What is the “trigger period” In Sentinel Insurance Company, Ltd. v. First Insurance Company of Hawai’i, Ltd., 76 Hawai'i 277, 875 P.2d 894 (1994), the Supreme Court of Hawai’i explained: Particular difficulty has been encountered when an injury process is not a definite, discrete event-for example, where the damage continues progressively over time spanning different insurer's policy terms. In this situation, courts have invoked an equitable “continuous injury” trigger of coverage. Under this theory, property damage is deemed to have “occurred” continuously for a fixed period (the “trigger period”), and every insurer on the risk at any time during that trigger period is jointly and 2 severally liable to the extent of their policy limits, the entire loss being equitably allocated among the insurers…The trigger period begins with the inception of the injury and ends when the injury ceases… Before the continuous injury trigger may be applied, the party urging its application must make two factual showings. It must be established that: (1) some kind of property damage occurred during the coverage period of each policy under which recovery is sought; and (2) the property damage was part of a continuous and indivisible process of injury. Sentinel Insurance Company, 76 Hawai'i at 298, 875 P.2d at 915 (citations omitted). B. The trigger period under South Carolina’s injury-in-fact/continuous trigger theory The South Carolina Supreme court has adopted the modified continuous trigger theory. “We hold coverage is triggered at the time of an injury-in-fact and continuously thereafter to allow coverage under all policies in effect from the time of injury-in-fact during the progressive damage.” Joe Harden Builders, Inc. v. Aetna Cas. and Sur. Co., 326 S.C. 231, 236, 486 S.E.2d 89, 91 (1997). Applying this principle to our example, the trigger period would begin when the work was completed (10/31/01) and the damage began to occur and would end with settlement at mediation (6/07). See Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich US, 377 F.Supp.2d 496 (D.S.C. 2004). II. Principal Theories of Coverage Allocation Among Successive Insurers A. Per Capita Under this theory, the risk is allocated equally among the policies triggered. This theory was advanced by the plaintiff but rejected by the Court in Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich US, supra. Assuming that the loss does not exceed the primary limits and applying the per capita approach to our example, each CGL carrier would each be responsible for one-third of the loss. 3 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #3 $500,000 CSL 1/3 B. 1/3 1/3 Pro Rata by Policy Period (time on the risk) Under this theory, damages are allocated among the carriers whose policies have been triggered according to the amount of triggered time on the risk (years, months). The seminal case adopting this theory of allocation was Insurance Co. of North America v. Forty-Eight Insulations, Inc., 633 F.2d 1212 (6th Cir. 1980), clarified 657 F.2d 814 (6th Cir. 1981). This theory was adopted by the Sentinel Insurance court and cited with approval in Joe Harden Builders and Auto-Owners v. Zurich. The Fourth Circuit adopted this approach, citing Sentinel Insurance in Spartan Petroleum, Co. v. Federated Mutual Ins. Co., 162 F.3d 805 (4th Cir. 1998). Assuming that the loss does not exceed the primary limits and applying the time on the risk method to our example, CGL #1 would be responsible for 2/50th or 4% of the loss (10/31/01 to 12/31/01), CGL #2 would have 36/50th or 72% of the loss (12/31/01 to 12/31/04) and CGL #3 would have 12/50th or 24% of the loss. 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 0 months CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 2 months 2/50=4% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/50=24% 4 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/50=24% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/50=24% CGL #3 $500,000 CSL 12 months 12/50=24% CGL #1 CGL #2 CGL #3 C. 4% 72% 24% Pro Rata by Policy Limits This theory allocates the loss by proration according to the ratio of the coverage provided by each policy for the same loss to the total coverage provided by all policies. It is favored by some courts since it reflects the degree of risk taken and premiums charged. However, the courts favoring this approach usually do so in cases of concurring coverage, such as multiple liability policies affording coverage in a car wreck. Our example involves a progressive loss. The pro rata by policy limits is not readily adaptable to this type of loss. Decisions adopting this approach are Nationwide Mutual Ins. Co. v. Hall, 643 So.2d 551 (Ala. 1994); Columbia Mutual Ins. Co. v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Ins. Co., 905 P.2d 474 (Alaska 1995); Fremont Indemnity Co. v. New England Reinsurance Co., 168 Ariz. 476, 815 P.2d 403 (1991); Allstate Ins. Co. v. Executive Car and Truck Leasing, Inc., 494 So.2d 487 (Fla. 1986); Empire Fire and Marine Ins. Co. v. North Pacific Ins. Co., 127 Idaho 716, 905 P.2d 1025 (1995); AID Ins. Co. v. United Fire Casualty Co., 445 N.W.2d 767 (Iowa 1989); Allstate Ins. Co. v. Chicago Ins. Co., 676 So.2d 271 (Miss. 1996); Bill Atkin Volkswagen, Inc. v. McClafferty, 213 Mont. 99, 689 P.2d 1237 (1984); Universal Underwriters Ins. Co. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 134 N.H. 315, 592 A.2d 515 (1991); CC Housing Corp. v. Ryder Truck Rental, Inc., 106 N.M. 577, 746 P.2d 1109 (1987); The Buckeye Union Ins. Co. v. State Automobile Mutual Ins. Co., 49 Ohio St.2d 213, 361 N.E.2d 1052 (1977); State Capital Ins. Co. v. The Mutual Assurance Society, 218 Va. 815, 241 S.E.2d 759 (1978). 5 D. Weighted Pro Rata Allocation Other courts have adopted a variation of the policy limits approach better suited to a progressive loss with a “long tail”. A good example is the Supreme Court of New Jersey’s decision in Owens-Illinois, Inc. v. United Ins. Co., 650 A.2d 974 (N.J. 1994). In that asbestos case, the court adopted an equitable allocation based upon a proration on the basis of policy limits, multiplied by years of coverage. This method can be demonstrated in our example: 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 N/A CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 $1 M/ $7.5 M 13.33% CGL #1 CGL #2 CGL #3 E. CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2 M/ $7.5 M 26.66% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2 M/ $7.5 M 26.66% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2 M/ $7.5 M 26.66% CGL #3 $500,000 CSL $.5 M/ $7.5 M 6.66% 13.33% 80.00% 6.66% Joint-and-Several Allocation In contrast to the pro rata method of allocation, joint and several allocation allows the insured to select the policy it wants to respond to the entire loss. That carrier must then seek contribution from any other carriers. Joint and several allows the insured to pick higher limits and no deductible policies. Carriers do not like this method because it places the insured in control. This method was discussed and adopted in J. H. France Refractories Co. v. Allstate Ins. Co., 626 A.2d 502 (Pa. 1993) (asbestosis) and Keene Corp. v. Insurance Co. of North America, 667 F.2d 1034 (D.C. Cir. 1981) and other states as well. 6 F. Maximum Loss Allocation (or “Equal Shares Method”) The maximum loss or equal shares method prorates the loss based upon the maximum loss that each insurer standing alone would incur in the particular incident. Each carrier bears the same portion of the loss up to the lowest limit, then the remaining carriers bear the loss up to the next remaining lowest limit, and so on until the loss is covered. Assuming the entire loss is $6 million, this method gives us the following result in our example: 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 N/A CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 $1,000,000 16.66% CGL #1 CGL #2 CGL #3 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $1,500,000 25% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $1,500,000 25% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $1,500,000 25% CGL #3 $500,000 CSL $500,000 8.33% $1,000,000 or 16.66% $4,500,000 or 75.00% $500,000 or 8.33% G. Decisions adopting this approach are American Cas. Of Reading, Pa. v. PHICO Ins. Co., 702 A.2d 1050 (Pa. 1997)(medical malpractice), Western Casualty and Surety Co. v. Universal Underwriters Ins. Co., 232 Kan. 606, 657 P.2d 576 (1983)(auto liability); Carriers Ins. Co. v. American Policyholders' Ins. Co., 404 A.2d 216 (Me. 1979)(auto liability); Mission Ins. Co. v. United States Fire Ins. Co., 401 Mass. 492, 517 N.E.2d 463 (1988)(auto liability); American Nurses Association v. Passaic General Hospital, 98 N.J. 83, 484 A.2d 670 (1984)(malpractice); Mission Ins. Co. v. Allendale Mutual Ins. Co., 95 Wash.2d 464, 626 P.2d 505 (1981)(property loss).Allocation Among Primary and Excess Carriers In our example, at what point in the loss are the excess carriers required to respond? Most excess policies contain this (or similar) language: We will pay only the amount in excess of the sums actually payable under the terms of the underlying insurance. 7 “Underlying insurance” means the insurance afforded by the policies listed in the Schedule of Underlying Insurance contained in the Declarations including their renewals and replacements. So, in our example must all of the primary limits be exhausted before the excess carriers must respond (horizontal exhaustion)? 2000 2001 Horizontal Exhaustion 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 N/A CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 $1,000,000 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2,000,000 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2,000,000 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2,000,000 CGL #3 $500,000 CSL $500,000 OR is it sufficient for one year’s primary limits to be exhausted to trigger that year’s excess policy (vertical exhaustion)? 2000 2001 Vertical Exhaustion 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 N/A CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL CGL #3 $500,000 CSL CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL $2,000,000 Generally, jurisdictions that have adopted a pro rata form of allocation require horizontal exhaustion because the two are consistent. See, e.g., Carter-Wallace, Inc. v. Admiral Insurance Co., 712 A.2d 1116 (N.J. 1998) and Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Utica Mutual Insurance Company, et. al., 802 A.2d 1070 (Md. 2002). 8 Likewise, juridisdictions that have adopted joint and several liability generally require only vertical exhaustion for consistency. See, e.g., ABT Building Products v. National Union Fire Ins. Co., 472 F.3d 99 (4th Cir. 2006). Although no South Carolina case has dealt with allocation among excess carriers, presumably it will follow the time on the risk method (but you never know for sure). H. 1. Further Complications (It gets harder – not easier) Uninsured Periods Periods of time with no insurance can further complicate allocation issues if a pro rata method is used. With joint and several allocations, the insured can avoid this problem. Some courts have found it unfair for the insured to escape its share of the loss when it did not buy insurance to cover the risk. See Forty-Eight Insulations, supra. Other courts do not assess uninsured periods against the insured. J. H. France, supra. The Fourth Circuit addressed this issue in Spartan Petroleum Co. v. Federated Mut. Ins. Co., 162 F.3d 805 (4th Cir. 1998): If on remand the district court concludes that the contamination did reach the Roshto property during the period of the Federated policy, it will become necessary to allocate the costs of the Roshto settlement. The policy itself is silent on this issue. Although the parties have pointed us to no South Carolina law on the subject, and we have not found any, we follow those courts that have concluded that the injury-in-fact/continuous trigger, such as the one adopted in Joe Harden, requires both pro rata allocation and allocation to the insured for any periods of the progressive damage during which it was self-insured. Id., at 812. Eleven years later, there still appears to be no South Carolina case dealing with this particular issue. Nonetheless, it is not unusual for carriers to insist on a contribution from the insured to cover any uninsured periods in the trigger period. 9 In our example, the trigger period begins when the work was complete and ends (theoretically) when the case settles at the mediation in June 2007. Here is how the uninsured period affects a time on the risk allocation in our example: 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 0 months CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 2 months 2/68=2.9% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/68=17.65% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/68=17.65% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/68=17.65% CGL #3 $500,000 CSL 12 months 12/68=17.65% Uninsured period = 1/01/2006 through 6/30/2007 = 18 months. CGL #1 3% CGL #2 53% CGL #3 18% The Insured 26% Question: Does this result mean that since the GC closed its doors on December 31, 2005 and its uninsured portion is, therefore, uncollectible that the plaintiff cannot collect 26% of its verdict or judgment? Answer: Only the Supreme Court of South Carolina can answer this question. However, since the carriers’ obligation is to indemnify its insured, its indemnity obligation should be the measure of each carrier’s responsibility. With a defunct insured, that portion of the loss may well be lost. 2. Uninsured Claims In our example, there will be claims for property damage that are covered by the CGL policies and there will be claims for building code violations that will not be covered. Settlement negotiations almost always trigger insurer’s claims of non-covered elements of damage. Suppose the insurer denies coverage and refuses to defend 10 causing the insured to settle the claim and sue the insurer for indemnity. In that circumstance, some courts require the insured to establish those damages covered by the CGL policy. Perdue Farms v. Travelers Cas. & Sur. Co., 448 F.3d 252 (4th Cir. 2006). Other courts require another trial to determine which damages are covered if the first trial resulted in a general verdict. See St. Paul Fire & Marine Ins. Co. v. Engelmann, 639 N.W.2d 192 (S.D. 2002) (where general verdict was given, part of the damages that could be allocated to covered negligence theory had to be relitigated); Agency of Natural Resources v. United States Fire Ins. Co., 796 A.2d 476 (Vt. 2001) (in pollution claim, remanding for determination of what portion of damages applied to the insured's property (not-covered) and what portion applied to third-party property (covered)); Bohrer v. Church Mut. Ins. Co., 965 P.2d 1258 (Colo. 1998) (remanding case to trial court for determination of which portion of jury verdict applied to the policyholder's counseling activities (covered) and which portion applied to the policyholder's sexual misconduct toward his client (not covered)). However, if a carrier denies coverage and does not defend, it can be held liable for the entire general verdict. Peterborough Oil Co., Inc. v. Great Am. Ins. Co., 397 F. Supp. 2d 230 (D. Mass. 2005) (insurer that failed to defend was liable for entire amount of judgment where there was no way to allocate between covered and non-covered claims). Not infrequently, complaints filed against insureds allege causes of action covered by the policy and causes of action which are not covered by the policy. Although the duty to defend may be clear cut in such a case, issues regarding the insurer's duty to indemnify the insured for any judgment entered against it remain. In such a case, particularly where common issues of fact are determinative of both the insured's liability to 11 the tortfeasor and the insurer's liability to pay any judgment, practicalities dictate that intervention by the insurer would be appropriate. Because the insured or its assign typically bears the burden to prove coverage for damages, case law suggests that if the insurer knows that an allocation of covered versus non-covered damages is required to preserve the insured's claim for coverage and the insurer fails to inform its insured of the need to make such an allocation, the insurer may be bound to pay a general verdict that fails to make such an allocation. Duke v. Hoch, 468 F.2d 973, 979 (5th Cir. 1972) (Insurer's reservation of rights was insufficient notice to insured that insured should protect its interests and the ability to establish coverage by requesting an appropriate verdict form. Under the circumstances, the insurer was required to prove that the damages in the unallocated general verdict were not covered rather than the insured proving coverage). 1Law and Prac. of Ins. Coverage Litig. § 12:22. Some courts permit these actions and some do not. See id. at §§ 12:17 to § 12:22. 3. Non-cumulation and Anti-stacking clauses One of the insurance industry’s many responses to Montrose Chemical Corp. v. Admiral Ins. Co., 10 Cal. 4th 645, 42 Cal. Rptr. 2d 324, 913 P.2d 878, 41 Env't. Rep. Cas. (BNA) 1714 (1995), and other decisions adopting the continuous trigger rule is the non-cumulation or anti-stacking clause. Its purpose is to prevent horizontal stacking of limits in the event of a progressive loss. A typical clause reads: Two or More Coverage Forms or Policies Issued By Us. If this coverage form and any other coverage form or policy issued to you by us or any company affiliated with us apply to the same “occurrence”, the maximum limit of insurance under all the coverage forms or policies shall not exceed the highest applicable limit of insurance under any one coverage form or policy. Another type of clause reduces the insurance available under a policy by the amount of insurance available to the insured under a prior policy issued by that same insurer. In either case, the result is the same – one limit of liability. 12 Some courts enforce these clauses, see, e.g. Endicott Johnson Corp. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 928 F. Supp. 176 (N.D. N.Y. 1996); I-O Brockway Glass Container, Inc. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 1994 WL 910935 (D.N.J. 1994); Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. v. Hartford Acc. and Indem. Co., 1989 WL 73656 (E.D. Pa. 1989); Reliance Ins. Co. v. Treasure Coast Travel Agency, Inc., 660 So. 2d 1136 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 4th Dist. 1995); State ex rel. Guste v. Aetna Cas. and Sur. Co., 429 So. 2d 106 (La. 1983) (surety bond); Graphic Arts Mut. Ins. v. C.W. Warthen, 240 Va. 457, 397 S.E.2d 876 (1990), but others have held that limiting coverage to only one year's policy limit when the insured has paid several years' premiums is contrary to the insured's reasonable expectation of coverage. E.g., In re Endeco, Inc., 718 F.2d 879, Bankr. L. Rep. (CCH) P 69426 (8th Cir. 1983); Standard Acc Ins Co v. Collingdale State Bank, 85 F.2d 375, 376 (3d Cir. 1936); A.B.S. Clothing Collection, Inc. v. Home Ins. Co., 34 Cal. App. 4th 1470, 41 Cal. Rptr. 2d 166, 170–173, (1995); Penalosa Co-op. Exchange v. Farmland Mut. Ins. Co., 14 Kan. App. 2d 321, 789 P.2d 1196, 1200 (1990); Hood ex rel. Bank of Summerfield v. Simpson, 206 N.C. 748, 175 S.E. 193, 199 (1934). Still other courts have found these clauses void for public policy reasons. Spaulding Composites Co., Inc. v. Aetna Cas. and Sur. Co., 176 N.J. 25, 819 A.2d 410, 420–22 (2003); Outboard Marine Corp. v. Liberty Mut. Ins. Co., 283 Ill. App. 3d 630, 219 Ill. Dec. 62, 670 N.E.2d 740 (2d Dist. 1996). Finally, some courts have found the clauses ambiguous and construed them against the insurer. E.g., Federal Ins. Co. By and Through Associated Aviation Underwriters v. Purex Industries, Inc., 972 F. Supp. 872 (D.N.J. 1997); A.B.S. Clothing 13 Collection, Inc. v. Home Ins. Co., 34 Cal. App. 4th 1470, 41 Cal. Rptr. 2d 166 (2d Dist. 1995). The Supreme Court of South Carolina has not yet decided a case involving a progressive loss with an anti-stacking clause in one or more of the CGL polices. However, if it acts consistently with earlier decisions in the auto liability context, the Court will uphold the clause. In our example, if the settlement is $6 million and the last 2 years of CGL #2 policies and the CGL #3 policy each contains an enforceable anti-stacking clause, the result would be: 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS EXCESS CGL #1 $10,000,000 CGL #1 $10,000,000 EXCESS #1 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #2 $10,000,000 CGL #3 $3,000,000 PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY PRIMARY CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 CGL #1 $1,000,000/ $2,000,000 2 months 2/68=2.9% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL 12 months 12/68=17.65% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL Uninsured 12/68=17.65% CGL #2 $2,000,000 CSL Uninsured 12/68=17.65% CGL #3 $500,000 CSL 12 months 12/68=17.65% Uninsured period = 1/01/2003 through 12/31/2004 and 1/01/2006 through 6/30/2007 = 42 months. CGL #1 CGL #2 CGL #3 The Insured $ 180,000 or 3% $1,050,000 or 17.50% $1,050,000 or 17.50% $3,720,000 or 62% Question: Why aren’t the excess policies for 2003 and 2004 triggered? Answer: These excess policies will not be triggered until all of the underlying available primary coverage has been exhausted. Because they typically tie their coverage to what is covered by the underlying primary coverage, the excess policy may bootstrap itself into a primary policy exclusion condition. Here, because we allocate pro 14 rata based upon time on the risk and we have uninsured periods, the primary coverages for 2001, 2002 and 2005 will not be exhausted. 4. The Montrose Provision Since 2001, the standard ISO policy form has contained the following language: b. This insurance applies to “bodily injury” and “property damage” only if:…. (3) Prior to the policy period, no insured listed under Paragraph 1. of Section II — Who Is An Insured and no “employee” authorized by you to give or receive notice of an “occurrence” or claim, knew that the “bodily injury” or “property damage” had occurred, in whole or in part. If such a listed insured or authorized “employee” knew, prior to the policy period, that the “bodily injury” or “property damage” occurred, then any continuation, change or resumption of such “bodily injury” or “property damage” during or after the policy period will be deemed to have been known prior to the policy period. c. “Bodily injury” or “property damage” which occurs during the policy period and was not, prior to the policy period, known to have occurred by any insured listed under Paragraph 1. of Section II — Who Is An Insured or any “employee” authorized by you to give or receive notice of an “occurrence” or claim, includes any continuation, change or resumption of that “bodily injury” or “property damage” after the end of the policy period.d. “Bodily injury” or “property damage” will be deemed to have been known to have occurred at the earliest time when any insured listed under Paragraph 1. of Section II — Who Is An Insured or any “employee” authorized by you to give or receive notice of an “occurrence” or claim:(1) Reports all, or any part, of the “bodily injury” or “property damage” to us or any other insurer; (2) Receives a written or verbal demand or claim for damages because of the “bodily injury” or “property damage”; or (3) Becomes aware by any other means that “bodily injury” or “property damage” has occurred or has begun to occur. In what appears to be the only case that has considered this provision, the courtenforced it under the principles of Known Loss Rule and upheld the denial of 15 coverage. Central Mut. Ins. Co. v. Useong Intern., Ltd., 394 F. Supp. 2d 1043, 1053 (N.D. Ill. 2005). 5. The Deemer Clause Deemer clauses attempt to limit the effect of this expansive coverage by deeming all such continuing property damage to have occurred in a single policy period. There are no standardized forms for this clause but one such endorsement provides: All property damage or bodily injury arising from, caused by or contributed to by, or in consequence of an occurrence shall be deemed to take place at the time of the first such damage, even though the nature and extent of such damage or injury may change and even though the damage may be continuous, progressive, cumulative, changing or evolving, and even though the occurrence causing such bodily injury or property damage may be continuous or repeated exposure to substantially the same general harm. At least one court addressing this clause has enforced it. USF Ins. Co. v. Clarendon America Ins. Co., 452 F. Supp. 2d 972 (C.D. Cal. 2006). In the other published case, involving a framing contractor, the court noted that the deemer clause did not provide coverage for property damage arising prior to the inception of, but continuing into, the Policy period. Had the facts supported it, apparently the Court would have enforced it. Gary G. Day Constr. Co., Inc. v. Clarendon America Ins. Co., 459 F. Supp. 2d 1039 (D. Nev. 2006). 6. Known Prior Claims Exclusion There is no standard Known Prior Claims Exclusion promulgated by ISO. However, several different carriers are attaching variations of it to CGL policies in manuscripted endorsements. One such variation provides: The insurance company will not cover claims or suits made or brought against the insured that the insured knew about, or that the insured could have foreseen or discovered in a reasonable way, prior to the effective 16 date of this agreement. This exclusion was reviewed in several cases with varying results. See Essex Ins. Co. v. H & H Land Development Corp., 525 F. Supp. 2d 1344, 1346–47 (M.D. Ga. 2007)(material facts prevented application of clause) and St. Paul Fire and Marine Ins. Co. v. MetPath, Inc., 38 F. Supp. 2d 1087, 1094–95 (D. Minn. 1998)(clause ambiguous); Cf. HR Acquisition I Corp. v. Twin City Fire Ins. Co., 547 F.3d 1309 (11th Cir. 2008) (Ala. law) (no coverage because of Prior Litigation Exclusion). 7. The Continuous or Progressive Injury and Damage Exclusion These exclusions also take different forms. One form is: This insurance does not apply to any damages because of or related to “bodily injury,” “property damage,” or “personal” and “advertising injury:” (1) which first existed, or alleged to have first existed, prior to the inception date of this policy; or (2) which are, or are alleged to be, in the process of taking place prior to the inception date of this policy, even if the actual or alleged “bodily injury,” “property damage,” or “personal and advertising injury” continues during this policy period; or (3) which were caused, or are alleged to have been caused, by the same condition which resulted in “bodily injury,” “property damage,” or “personal and advertising injury” which first existed prior to the inception date of this policy. We shall have no duty to defend any insured against any loss, claim, “suit,” or other proceeding alleging damages arising out of or related to “bodily injury,” “property damage,” or “personal and advertising injury” to which this endorsement applies. This exclusion is very similar to the Montrose Provision in the body of ISO form policies, except that it excludes all previously occurring bodily injury or property damage as opposed to precluding coverage for those instances of injury and damage of which the insured should have been aware before the inception of the policy. Like the Montrose Provision, this exclusion is one of the various intended means of limiting the 17 effect of the Continuous Trigger. In Williams Consolidated I, Ltd./BSI Holdings, Inc. v. TIG Ins. Co., 230 S.W.3d 895, 902–03 (Tex. App. 2007), the insured was a subcontractor who installed a defective vapor barrier. The policy contained this exclusion: No insurance coverage is provided under this policy to defend or indemnify any insured for “bodily injury,” “property damage,” “personal injury,” or “advertising injury” which has first occurred or begun prior to the effective date of this policy, regardless of whether repeated or continued exposure to conditions which were a cause of such for [sic] “bodily injury,” “property damage,” “personal injury” or “advertising injury” occurs during the period of this policy and cause [sic] additional, progressive or further “bodily injury,” “property damage,” “personal injury,” or “advertising injury” all of which is excluded from coverage. This exclusion shall apply whether or not the Insured's legal obligation to pay damages has been established as of the inception date of this policy. The court found: [T]here is no coverage for alleged property damage or bodily injury that first occurred or began before the effective date of the CGL Policy. However, if the alleged property damage or bodily injury did not occur or begin before the effective date but the alleged process leading to the ultimate injury or damage began before that date, coverage is not excluded for this reason. Id. at 902. 8. The Known Loss Rule “As most often stated, the known loss doctrine in common law insurance jurisprudence excludes coverage of a loss to the insured of which the insured had actual knowledge prior to the policy's effective date or knew was substantially certain to occur.” Stonehenge Engineering Corporation v. Employer’s Insurance of Wausau, 201 F.3d 296 (4th Cir. 2000). With no state case law on the doctrine, Stonehenge remains 18 the sole predictor of what our state appellate courts will do. To determine whether the known loss rule applied, the Fourth Circuit observed: Therefore, the question before us is whether the evidence, when viewed in the light most favorable to Wausau, establishes that Stonehenge (1) actually knew that it was legally liable for the property damage claimed by the Owners Association at the time one or more of the Three Wausau Policies took effect or (2) knew that such liability was substantially certain to occur. Id., at 302.The Fourth Circuit panel found that the insured in the case did not have that certainty of knowledge required to apply the Known Loss Rule. III. Application to Construction Defect Claims in South Carolina From an application of these principles and the few South Carolina cases on the subject, we can conclude: A. South Carolina applies the injury in fact/continuous trigger (or modified continuous trigger) theory in progressive property damage cases. See Joe Harden Builders; Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich; Century Indemnity Company v. Golden Hills Builders, 348 S.C. 559, 561 S.E.2d 355 (2002). B. The trigger period in South Carolina starts when the damage first occurs and ends when the damage ceases in fact (i.e., is repaired) or in law (settlement or verdict). See Joe Harden Builders; Sentinel Insurance Company, Ltd.; Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich. C. Progressive property damage that can be specifically attributed to a certain policy period is covered under that policy. Sentinel Insurance Company, Ltd. D. Progressive property damage that cannot be specifically attributed to a certain policy period is covered under the policy in effect at the time the damage first occurred and triggers all subsequent policies while the damage continues. Joe Harden Builders. E. The policy in effect at the time the damage first occurs (the injury in fact) covers damage during that policy period and any continuing damage. Century Indemnity Company, supra. 19 F. Allocation among primary carriers in South Carolina will be based upon their pro rated time on the risk. Sentinel Insurance Company, Ltd., supra.; Joe Harden Builders; Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich, supra. G. South Carolina will likely follow a horizontal exhaustion scheme since it has adopted the injury in fact/continuous trigger theory. See Mayor and City Council of Baltimore v. Utica Mutual Insurance Company, et. al., 802 A.2d 1070 (Md. 2002). H. South Carolina will likely enforce anti-stacking clauses. Ruppe v. AutoOwners Insurance Company, 496 S.E.2d 631 (SC 1998)( anti-stacking clause that prohibited intra-policy stacking of liability coverage was valid); Jackson v. State Farm Mut. Auto Ins. Co., 342 S.E.2d 603 (S.C. 1986) (stacking may be prohibited by contract if not statutorily required coverage). I South Carolina will likely enforce the Montrose clause and exclusions designed to prevent multiple triggers of coverage. Willis v. Fidelity & Cas. Co., 169 S.E.2d 282 (S.C. 1969) (parties are free to choose their terms regarding voluntary coverage not governed by statute) Nagging Questions: 1. How do you reconcile a time on the risk allocation with Century Indemnity Company? In Century Indemnity Company, the Supreme Court said that “[b]ecause the policy at issue here contains substantially the same language as the policy at issue in Joe Harden, the modified continuous trigger theory applies in the instant case. As a result, the insurance policy provides coverage for property damage that occurred during the policy period and for any continuing damage.” Century Indemnity Company, supra, at 358. The application of time on the risk yields responsibility for a pro rata percentage of the loss, not the entire loss. Isn’t making each carrier responsible for the entire loss equivalent to “joint and several” allocation? If that is so, might we really be a “joint and several” state? 2. Will South Carolina impose uninsured allocation periods on the insured? In Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich, the trigger period began with the completion of the home on July 26, 1996 and ended with the arbitrator’s award on April 29, 2002, a total period of 69 months. (Somehow the parties came up with 75 months) Zurich’s policy was in effect for 3 of those months (July 26, 1996 through October 27, 1996). Auto-Owner’s policy was in effect for 48 of those months (October 27, 1996 through October 27, 2000). Whether the total trigger period was 69 or 75 months, it is clear from the opinion that these two carriers did not have coverage for the entire trigger period. Approximately 18 months of the trigger period (October 27, 2000 to April 29, 2002) are not allocated under a time on the risk allocation. Rather, the Court first determined that Zurich was responsible for 3/75 of the loss and that Auto-Owners was responsible for the rest. There was only a partial time on the risk analysis. If the Court was going to 20 follow the Spartan Petroleum case which it cited and which is binding on the Court, why did it not allocate those 18 months to the insured? 3. Is property damage caused by a subcontractor’s faulty workmanship covered under the CGL or not? In Century Indemnity Company (a 2002 residential EIFS case), the Supreme Court held that “Based on the law of this State, coverage for the repair and/or replacement of the substrate and substructure of the home is excluded by the faulty workmanship provision.” Supra, at 359. The Court called the “your work” exclusion the “faulty workmanship” exclusion. However, in Auto-Owners Ins. Co. v. Newman (a 2009 residential EIFS case), the Supreme Court held – “Accordingly, we hold that the subcontractor's negligence resulted in an “occurrence” falling within the CGL policy's initial grant of coverage for the resulting “property damage” to the home's framing and exterior sheathing. .. The facts of this case establish exactly the type of property damage the CGL policy was intended to cover after the 1986 amendment to the “your work” exclusion.” In each case, the alleged faulty workmanship was performed by a subcontractor. In each case, the CGL policy reflected the 1986 amendment to the “your work” exclusion. The only mention of Century Indemnity Company in the Newman case was by Justice Pleicones in his dissent. 4. What kind of allocation method was the Fourth Circuit thinking about in Stonehenge Engineering Corporation? I have no idea and I was there. Stonehenge v. Wausau Allocation Gone Awry 4/1/85 – 7/1/86 Unknown 16 months 10.6% 7/1/86 – 11/1/87 Maryland Cas. 16 months 11.3% 11/1/87 – 11/1/91 Aetna 48 months 33.9% 11/1/91 – 11/1/92 Home Ins. Co. 12 months 8.5% 11/1/92 – 11/1/95 Wausau 36 months 25.4% 11/1/95 – 3/17/97 Uninsured 16.5 months 10.3% Total Trigger Period = 144.5 months Total Coverage Period = 112 months Wausau’s Share = Pro rata time on risk (trigger period) x amount of judgment Wausau’s Share = 25.4% of $750,000 = $190,500 (District Court; Judge Shedd) 4th Circuit: $ Basis of Allocation: Time Basis of Allocation: $475,000, amount paid by other carriers ??? Trigger Period (144.5 months) 21 Dissent (J. Traxler): $ Basis of Allocation?: $750,000 confession of judgment $625,000 settlement demand $475,000 paid by other carriers Time Basis of Allocation: Trigger Period (144.5 months) or Carrier Maryland Casualty Aetna Home Ins. Co. Wausau Uninsured Carrier Maryland Casualty Aetna Home Ins. Co. Wausau Uninsured Carrier Maryland Casualty Aetna Home Ins. Co. Wausau Total Paid Trigger Period 144.5 months 11.3% 33.9% 8.5% 25.4% 20.9% Allocation of $750,000 $ 84,750 $254,250 $ 75,000 $190,500 $156,750 Coverage Period 112 months 14.3% 42.9% 10.7% 32.14% Allocation of $750,000 $ 107,250 $ 321,750 $ 80,250 $241,050 Amount Paid $100,000 $300,000 $ 75,000 $120,650 Trigger Period 144.5 months 11.3% 33.9% 8.5% 25.4% 20.9% Allocation of $625,000 $ 70,625 $ 211,875 $ 53,125 $ 158,750 $ 130,625 Coverage Period 112 months 14.3% 42.9% 10.7% 32.14% Allocation of $625,000 $ 89,375 $ 268,125 $ 66,875 $ 200,875 Amount Paid $100,000 $300,000 $ 75,000 $120,650 Amount Paid $100,000 $300,000 $ 75,000 $120,650 $595,650 % Allocation 16.78 % 50.37 % 12.6 % 20.25 % Cases to know: Sentinel Insurance Company, Ltd. v. First Insurance Company of Hawai’i, Ltd., 875 P. 2d 894, 915 (Hawai’i 1994) Joe Harden Builders, Inc. v. Aetna Cas. and Sur. Co., 486 S.E.2d 89, 91 (SC 1997) Spartan Petroleum Co. v. Federated Mut. Ins. Co., 162 F.3d 805 (4th Cir. 1998) Stonehenge Engineering Corporation v. Employer’s Insurance of Wausau, 201 F.3d 296 (4th Cir. 2000) Century Indemnity Company v. Golden Hills Builders, 348 S.C. 559, 561 S.E.2d 355 (2002) 22 Auto-Owners Insurance Co., Inc. v. Zurich, US, 377 F.Supp.2d 496 (DCSC 2004) L-J, Inc. v. Bituminous Fire and Marine Insurance Co., 366 S.C. 117, 621 S.E.2d 33 (2005) Auto-Owners Ins. Co. v. Newman, 385 S.C. 187, 2009 WL 2851211 (2009) 23