commercial general liability

advertisement

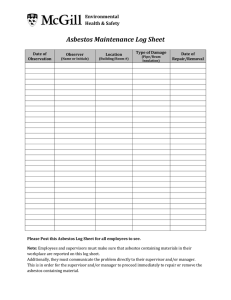

September 2015 Volume 6 Issue 9 COMMERCIAL GENERAL LIABILITY D I S PAT C H MEET OUR EDITORS JOANNA L. CROSBY, Partner New Jersey Office | jcrosby@tresslerllp.com TOP STORIES >> CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT OVERRULES HENKEL, FINDING CONSENT-TO-ASSIGNMENT CLAUSES ARE UNENFORCEABLE FOR POSTLOSS ASSIGNMENT OF INSURANCE COVERAGE RIGHTS By: Elizabeth Musser, Partner in the Los Angeles Office............................................. P2 LINDA TAI HOSHIDE, Partner Los Angeles Office | lhoshide@tresslerllp.com >> THE 10TH CIRCUIT DEMONSTRATES THAT LIMITING OR EXCLUDING L ANGUAGE CAN BE A POWERFUL TOOL TO INSURERS By: Si-Yong Yi, Associate in the Chicago Office........................................................... P3 >> CALIFORNIA COURT MAKES AN END RUN AROUND ASBESTOS AND TOTAL POLLUTION EXCLUSIONS TO FIND DUTY TO DEFEND By: Mary McPherson, Partner in the Orange County Office....................................... P4 >> CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT FINDS CUMIS COUNSEL DIRECTLY LIABLE IN LIMITED CIRCUMSTANCES FOR UNNECESSARY AND UNREASONABLE FEES By: Kate Tammaro, Partner in the New Jersey Office.................................................. P7 JAMES A. PINDERSKI, Partner Chicago Office | jpinderski@tresslerllp.com CONTRIBUTING EDITORS REGISTRATION NOW OPEN!.................................................................................... P5 STRATEGIES FOR WINNING BAD FAITH TRIALS SEMINAR CHICAGO, IL | WILLIS TOWER CALIFORNIA | ILLINOIS | NEW JERSEY | NEW YORK Amber Coisman | Yvonne Schulte California Supreme Court Overrules Henkel, Finding Consent-to-Assignment Clauses are Unenforceable for Postloss Assignment of Insurance Coverage Rights The California Supreme Court overruled its decision in Henkel Corp v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co., 29 Cal. 4th 934 (2003), applying a rarely-cited statute to find that consent-to-assignment clauses are unenforceable for postloss assignments of insurance coverage rights. Fluor Corp. v. Super. Ct., 61 Cal. 4th 1175 (Aug. 20, 2015). Elizabeth Musser Partner in the Los Angeles Office Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co. provided general liability coverage to Fluor Corporation – a company providing engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) services – under 11 policies from 1971 to 1986. Each of the Hartford policies contains a consent-to-assignment clause, which states, “Assignment of interest under this policy shall not bind the Company until its consent is endorsed hereon.” Beginning in the 1980s, Fluor was named as a defendant in many asbestos-related lawsuits, for which Hartford and other carriers provided coverage. Also in the 1980s, Fluor acquired mining business A.T. Massey Coal Company as a subsidiary. In September 2000, in a corporate restructuring known as a “reverse spinoff,” Fluor created a subsidiary called “Fluor Corporation” (New Fluor), and changed the name of the original Fluor to “Massey Energy Company.” Fluor transferred all EPC assets and liabilities to New Fluor (the parties dispute whether the transfer of assets and liabilities included Fluor’s insurance policies, but the Court does not address that issue in its opinion). New Fluor advised Hartford of the reverse spinoff in May 2001. Hartford continued to defend New Fluor in asbestos-related lawsuits. In a coverage action in 2009, Hartford asserted in a crosscomplaint that Fluor failed to comply with the consent-toassignment clauses in its policies in transferring assets to New Fluor. Hartford relied on the California Supreme Court’s decision in Henkel Corp v. Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co., 29 Cal. 4th 934 (2003). In Henkel, the California Supreme Court enforced a consent-to-assignment clause postloss, finding that the clause was enforceable if the attempted assignment was made before the underlying claims were reduced to a judgment for a sum of money due. New Fluor argued that application of Hartford’s consent-toassignment clause was barred by California Insurance Code section 520, which provides, “An agreement not to transfer the claim of the insured against the insurer after a loss has happened, is void if made before the loss ….” The Court in Henkel did not consider section 520, which was originally enacted as a civil statute in 1872 (when liability insurance did not exist), was transferred to the California Insurance Code in 1935, amended in 1947, and has very rarely been invoked in recent decades. It appears that neither the insured’s nor the insurer’s counsel raised section 520 in the P. 2 www.tresslerllp.com briefing or argument in Henkel, and that none of the amicus curiae briefs addressed the statute. The California Court of Appeal applied Henkel to determine that Hartford could rely on its consent-to-assignment clause, so that any assignment of rights under its policies before any claims were reduced to a judgment was void. The Court of Appeal addressed New Fluor’s argument about the potential applicability of section 520, and found that the statute applies only to first-party insurance, not to third-party liability insurance. The California Supreme Court reversed, overruling Henkel to the extent Henkel stands for the proposition that consent-toassignment clauses apply to any attempted assignment prior to judgment or settlement. The California Supreme Court first held that section 520 applies to third-party liability insurance, holding that nothing in the text of the statute limits its application to first-party insurance. Indeed, the legislature specifically transferred section 520 to California’s Insurance Code in 1935 (when liability insurance was fully available), and the legislature amended section 520 in 1947 (when liability insurance was even more common) to exempt life and disability insurance. According to the Court, these factors indicated that there is no reason to limit the statute to first-party insurance. Next, the Court addressed the meaning of the phrase “after a loss has happened” in the statute. The Court considered whether it refers to the occurrence of bodily injury or property damage, as urged by New Fluor, or whether it refers to judgment or settlement for a sum of money, as urged by Hartford. As part of its evaluation of the meaning of “after a loss has happened,” the Court engaged in a detailed analysis of nineteenth century legislative history for section 520 and a similar statute enacted in New York, and reviewed a series of early liability insurance coverage cases in California and nationwide. As a result of this analysis, the Court determined that early liability insurance cases held that an insured may assign its postloss insurance coverage rights, with or without the consent of the insurer. The idea driving these early liability decisions is that the insured loss happens at the time of injury during the policy period, so there is no need to continue to protect the insurer after the policy period, when the loss has already Continued from Page 1 occurred. (The Court noted that the purpose of consent-toassignment clauses is to protect the insurer from needing to provide coverage for losses it has not bargained to cover.) The Court opined that given the strong preference in the decisional law to allow assignment of postloss insurance coverage rights, Henkel is the anomaly. In light of the legislative history, survey of decisional law, and section 520, the California Supreme Court found that Hartford’s consentto-assignment clauses do not apply to assignment of postloss insurance coverage rights, thereby overruling Henkel. Tressler Comments This important case from California’s highest state court substantially changes California coverage law regarding consentto-assignment clauses, as discussed above. It demonstrates the enormous impact that a statute can have on decisional law, and the difficult burden in overcoming a statute that is apparently contrary to decisional law. In Frontier Oil Corp. v. RLI Insurance Co., 153 Cal. App. 4th 1436 (2007), a California Court of Appeal relied on California Civil Code section 1646 – also enacted in 1872 – to provide a seminal case on California’s choice of law principles. The Fluor decision is also notable for the California Supreme Court’s expansive discussion of legislative history and case law – only hinted at above – in which the Court tries to grapple with the development of liability insurance and attendant assignment rights. In any case involving the applicability of a statute, and particularly an older statute, litigants should research the legislative and decisional law history, and provide the court with an explanation as to the applicability (or inapplicability) of the statute at issue. The 10th Circuit Demonstrates that Limiting or Excluding Language Can Be a Powerful Tool to Insurers Si-Yong Yi Associate in the Chicago Office (No picture available) In Nationwide Mut. Ins. Co. v. Prater, 2015 WL 4665792 (10th Cir. 2015), the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the District Court’s finding that an insurance policy did not cover the claims that were excluded by the limiting provisions of the policy. Plaintiffs Wayne and Tonya Prater accompanied their children to a birthday party held at Kingdom Fitness & Fun, Inc. (Kingdom), a gymnastics facility. While at the party, Wayne Prater jumped from a platform into a foam pit, breaking his back and becoming paralyzed from the waist down. The Praters then filed suit against Kingdom, the individual owners of Kingdom, and the owner of the building and property where Kingdom operated. The insurance policy that Kingdom purchased from Nationwide Mutual Insurance Company (Nationwide) was sold as “gymnastics and cheerleading insurance,” and the insurance application form required Kingdom to identify the specific gymnastics-related activities it engages in and to report the total number of birthday or social parties it may hold at its facility on an annual basis. However, Kingdom did not indicate that it held birthday or social parties nor did it list the number of parties it hosted. Also, the “Exclusion – Designated Operations” section stated that the policy did not apply to the operations described in the Exclusion Schedule, which described Kingdom’s operations “as a sports complex or multi-purpose facility, except for those sport(s) and/or subsidiary activities you have reported, paid for, and that have been approved by the program administrator.” Nationwide filed a declaratory judgment action arguing that it had no duty to defend or to indemnify Kingdom because its policy did not cover birthday parties, and Prater’s injuries occurred during a birthday party. In its analysis, the 10th Circuit first considered whether the general coverage provisions of the policy covered Prater’s injuries. The policy stated Nationwide would pay those sums that the insured becomes legally obligated to pay as damages because of bodily injury “to which this insurance applies.” Because of this language, the 10th Circuit needed to examine other sections of the policy to determine whether Prater’s injury would be covered. The “Limitation of Coverage to Designated Premises, Activities or Operations” section of the policy stated, “If reported, approved and the applicable premium has been paid, covered operations include birthday/social party[s]...” The 10th Circuit found that because Kingdom did not report, obtain approval, P. 3 www.tresslerllp.com Continued from Page 3 or pay additional premium for birthday coverage, injuries occurring at birthday parties were not covered. In addition, the 10th Circuit rejected Prater’s contention that even if his injury was not covered under the general provisions of the policy, his injury was covered because of two endorsements: the Legal Liability to Participants endorsement and Professional Liability Coverage endorsement. The Legal Liability to Participants endorsement added coverage for bodily injury to a “Participant,” but this endorsement did not add coverage for Prater’s injury because the endorsement specifically excluded coverage for damages “to which this insurance does not apply.” Similarly, the Professional Liability Coverage endorsement also included a phrase excluding coverage for damages for wrongful acts “to which this insurance does not apply.” Further, the 10th Circuit found that even if the policy’s coverage provisions covered birthday parties not reported to or approved by Nationwide, the Exclusion provision of the policy would exclude coverage, as the birthday parties were part of Kingdom’s operations but were not reported or approved by Nationwide and paid for with separate premium. Tressler Comments This case illustrates how well written limitation/exclusion sections of a policy can effectively limit the scope of insurance coverage. Policy premiums and intent of the scope of coverage should be considered when reviewing coverage. The ExclusionDesignated Operations provisions deserve careful examination. REGISTER NOW! SEMINAR LOCATION Willis Tower, Chicago, IL 60606 October 15, 2015 8:15 AM - 4:30 PM STRATEGIES FOR WINNING BAD FAITH TRIALS *Please note, this seminar is only open to insurance company personnel and not attorneys in private practice. JOIN US!* Leading insurance and legal industry professionals will provide valuable insight on strategies for determining which bad faith cases should go to trial and how to handle and win those trials. CONTINUING EDUCATION: This program has been approved for CLE credit hours in CA, IL and NY. CE credit for insurance professionals will not be available. BROCHURE: CLICK HERE CLICK HERE TO REGISTER or visit: http://tresslerllp.com/WinningStrategiesChicago You can also register by contacting Liz Ashline at: lashline@tresslerllp.com. Seminar hosted by Tressler LLP. P. 4 www.tresslerllp.com California Court Makes an End Run Around Asbestos and Total Pollution Exclusions to Find Duty to Defend Mary McPherson Partner in the Orange County Office A federal District Court in San Francisco has ruled that an insurer had a duty to defend an apartment building owner and its general contractor in a suit brought by tenants who were allegedly exposed to asbestos during a construction project. Although the policy contained broad Asbestos and Total Pollution exclusions, the court found that the underlying allegations, i.e. wrongful entry into the tenants’ unit by the insureds and “constructive eviction” due to “dust, debris and unknown contaminants” in their units during an asbestos abatement project, included potentially covered claims, which fell outside these exclusions. Therefore, the insurer was obligated to defend both the building owner (its named insured) and the general contractor (additional insured) against the lawsuit. Parklyn Bay Co., LLC v. Liberty Insurance Corp., No. C-13-3124 EMC, 2015 WL 4760376 N.D. Cal., (August 12, 2015) (unpublished). In 2012, two tenants of an apartment building sued the building’s owner, Parklyn Bay Co., LLC (Building Owner), and its general contractor, Oliver and Co. (GC), alleging they had knowingly or negligently exposed the tenants to asbestos during a construction project undertaken to abate asbestos contained in the buildings (Lawsuit). The Lawsuit also alleged that when the tenants were out of their unit, “defendants and/or workers employed by defendants made multiple entries into the Premises without prior notice, and without the consent of plaintiffs.” The tenants further claimed that when “defendants began demotion of the unit directly above plaintiffs’ unit [it caused] large quantities of dust, debris, and unknown contaminants to enter into plaintiffs’ unit.” The Building Owner and GC both tendered their defense of the Lawsuit to the Building Owner’s commercial general liability insurer, Liberty Surplus Insurance Corp. (Liberty). Liberty denied coverage on the ground that the Lawsuit fell within the policy’s Asbestos and/or Total Pollution Exclusions. The Building Owner eventually settled the Lawsuit on behalf of itself and the GC, taking assignment of the GC’s coverage and bad faith claims against Liberty. Liberty’s policy definition of “personal and advertising injury,” included an offense of … (c) The wrongful eviction from, wrongful entry into, or invasion of the right of private occupancy or a room, dwelling or premises that a person occupies, committed by or on behalf of its owner, landlord or lessor[.] The policy’s Asbestos Exclusion barred coverage for “‘personal and advertising injury’ arising out of or related in any way, either directly or indirectly, to: (a) asbestos, asbestos products, asbestos-containing materials or products, asbestos fibers or asbestos dust, including, but not limited to, manufacture, mining, use, sale, installation, removal or distribution activities; (b) exposure to, testing for, monitoring of, cleaning up, removing, containing or treating asbestos, asbestos products, asbestos-containing materials or products, asbestos fibers or asbestos dust; and (c) any obligation to investigate, settle or defend, or indemnify any person against any claim or suit arising out of, or related in any way, either directly or indirectly, to asbestos products, asbestos-containing materials or products, asbestos fibers or asbestos dust. The policy also contained a Total Pollution Exclusion. The Building Owner and GC argued there was a duty to defend because, in addition to and separate from, the asbestos claims, plaintiffs’ claims were for unlawful entries into their units unrelated to the alleged exposure to asbestos: “During the time that plaintiffs were out of their unit, defendants and/or workers employed by defendants made multiple entries into the Premises without prior notice, and without consent of plaintiffs” (Paragraph 18). Liberty argued that, even though Paragraph 18 made no specific reference to asbestos, the asbestos exclusion applied because the reason Parklyn Bay and its employees allegedly made multiple entries into the apartment without notice or consent was “to abate the asbestos.” The court agreed with the Building Owner and GC, finding there was no allegation anywhere in the underlying complaint stating that the Building Owner or its GC repeatedly entered the tenants’ apartment without permission in order to abate asbestos. In the court’s view, the allegations of Paragraph 18 raised at least the potential for coverage under the “personal and advertising injury” provision, which expressly covered injuries “arising out of … [the] wrongful entry into, or invasion of the right of private occupancy or a room.” While recognizing Liberty could consider extrinsic evidence in determining the duty to defend, the court rejected Liberty’s argument that the Building Owner had “admitted” in its cross-complaint that the wrongful entries were related to asbestos removal. First, the court held the allegations in the Building Owner’s cross-complaint against GC that Liberty claimed were “admissions” were not, in fact, admissions. Second, Liberty failed to establish that it had knowledge of this alleged “admission” at the time it received the tenders from the Building Owner and GC. Thus, a cause of action for wrongful entry could lie even in the absence of asbestos. P. 5 www.tresslerllp.com Continued from Page 5 The court also found that the tenants’ allegations that they were forced to “flee” their apartment at least in part because of the “dust, debris, and unknown contaminants” provided an additional, independent basis for a duty to defend. As this allegation did not specifically state that the contaminants contained asbestos, and this fact was not established beyond dispute, the court found the Asbestos Exclusion did not apply to preclude a duty to defend. The court also found that Liberty failed to show that the “dust and debris” and “unknown contaminants” would necessarily fall within the policy’s Total Pollution Exclusion, citing to California decisions differentiating between “conventional environmental pollution” and “ordinary dust.” In reaching the conclusion that Liberty had a duty to defend, the court repeatedly focused on what the insurer knew and when it knew it, applying the general rule that a duty to defend depends on allegations and facts known at the time of tender. Tressler Comments Although the court’s ruling is questionable in light of what appears to be evidence that the construction activity were all for the purpose of abating asbestos, and the policy had a broad all encompassing asbestos exclusion, this unpublished decision reminds insurers that courts will go out of their way to find a duty to defend. Thus, it is important to consider whether any of the allegations could fall outside exclusions such as in this case, where the court found that an allegation of a wrongful entry, not specifically alleged to be related to the asbestos abatement activities, and/or allegations of wrongful eviction due to “dust and debris,” can be found to raise a possibility of coverage. This decision also reminds insurers that it is important to investigate as soon as the tender is received, as the court questioned whether the insurer knew, at the time it denied coverage, that all of the claims allegedly arose out of asbestos related activities or if it only determined that that was the only source of claims later in the litigation and not at the time the Lawsuit was originally tendered. ANNOUNCING TRESSLER LLP’S BLOG: www.PrivacyRiskReport.com It is virtually impossible to look at the news today without seeing a story involving cyber security and data breaches. For that reason, Tressler developed the Privacy Risk Report blog. >> CLICK HERE TO VISIT OUR BLOG. Did you know Tressler LLP is on Twitter? Follow us at @TresslerLLP for the latest newsworthy firm events, publications and attorney speaking engagements. Visit us at: https://twitter.com/TresslerLL P P. 6 www.tresslerllp.com California Supreme Court Finds Cumis Counsel Directly Liable in Limited Circumstances for Unnecessary and Unreasonable Fees Kate Tammaro Partner in the New Jersey Office In Hartford Cas. Ins. Co. v. J.R. Mktg., L.L.C., 61 Cal. 4th 988, 353 P.3d 319, 321 (Cal. Aug. 10, 2015), the California Supreme Court first acknowledges that under California law, if any claims in a third-party complaint against a person or entity protected by a commercial general liability (CGL) insurance policy are even potentially covered by the policy, the insurer must provide its insured with a defense to all the claims. It confirms that, pursuant to its previous decision in Buss v. Superior Court, 16 Cal.4th 35, 939 P.2d 766 (Cal. 1997), the insurer may seek reimbursement from the insured of defense fees and expenses solely attributable to the claims that were clearly outside policy coverage. The Court noted that this case presented a different factual scenario than that in Buss, which was fairly straightforward. In this case, Hartford Casualty Insurance Company (Hartford) initially refused to defend the insured against a third-party lawsuit, claiming that the acts alleged in the complaint took place prior to the policy period, and that certain of the defendants were not insureds under the Hartford policy. After a declaratory judgment where Hartford was found to have a duty to defend, the Court also ordered (i) that Hartford provide independent or Cumis counsel under a reservations of rights; and (2) pursuant to an order that was drafted by the law firm of Squire Sanders, the Cumis counsel selected by the insureds, Hartford to pay all “reasonable and necessary defense costs.” Even though the order stated that because of the breach of the duty to defend, Hartford would be precluded from “invok[ing] the rate provisions of Section 2860,” the order expressly preserved Hartford’s right to later challenge and recover payments for “unreasonable and unnecessary” charges by counsel. Hartford later alleged that the independent counsel “padded” their bills by charging fees that were, in part, excessive, unreasonable and unnecessary. Hartford’s lawsuit was filed against the insured and against Cumis counsel themselves. The Court concluded that under the circumstances of this case, the insurer may seek reimbursement directly from Cumis counsel under the equitable principles of restitution and unjust enrichment. If Cumis counsel, operating under a court order that expressly provided that the insurer would be able to recover payments of excessive fees, sought and received from the insurer payment for costs that were fraudulent, or were otherwise manifestly and objectively useless and wasteful when incurred, Cumis counsel have been unjustly enriched at the insurer’s expense. The Court found that Cumis counsel provided no convincing reason why they should be absolutely immune from liability for enriching themselves in this fashion. Cumis counsel failed to persuade that any financial responsibility for their excessive billing should fall first on their own clients – insureds who paid to receive a defense of potentially covered claims, not to face additional rounds of litigation and possible monetary exposure for the acts of their lawyers. The Court made no review and determination of whether the costs and fees incurred by Cumis counsel were, in fact, excessive. Tressler Comments The California Supreme Court explicitly reserved this ruling to the unique and specific facts of this case, allowing pursuit of Cumis counsel for reimbursement of unnecessary and unreasonable fees only in those circumstances where there is a previous order in place allowing the insurer to seek such reimbursement. However, there is no dispute, as recognized by the Court in its discussion of the background of this case, that California law under Buss, and later codified in statute, allows the insurer to seek reimbursement of uncovered defense fees if it reserves its right to do so. That statute, Section 2860, also requires that Cumis fees be necessary and reasonable. It seems that the Court’s requirement of a previous court order allowing recovery, (which order in this case was drafted by the Cumis counsel themselves) involves the issues of notice and fair warning to Cumis counsel of the potential for eventual recovery against it. In the absence of such an order, which would likely be the case in most instances, the insurer may attempt to execute a non-waiver agreement with the insured and Cumis counsel upon the acceptance of defense, that the insurer reserves the right to proceed against the Cumis counsel directly to recover “unnecessary and unreasonable” fees (uncovered defense costs may only be recovered from the insured itself). At the very least, if the insured and Cumis counsel will not agree, reservation language to this effect should be included in all position letters to attempt to preserve the right of recovery directly against the Cumis counsel. Whether the courts will expand the impact of this ruling beyond the facts of this case remains to be seen. P. 7 www.tresslerllp.com AUTHORS Elizabeth Musser Partner Los Angeles emusser@tresslerllp.com Mary McPherson Partner Orange County mmcpherson@tresslerllp.com (No picture available) LOCATIONS >> CHICAGO (HEADQUARTERS) Willis Tower: 233 South Wacker Drive, 22nd Floor, Chicago, IL 60606 312.627.4000 | Fax: 312.627.1717 Katherine E. Tammaro Partner New Jersey ktammaro@tresslerllp.com Si-Yong Yi Associate Chicago syi@tresslerllp.com >> CALIFORNIA Orange County: Jamboree Center, 2 Park Plaza, Suite 1050, Irvine, CA 92614 949.336.1200 | Fax: 949.752.0645 Los Angeles: 1901 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 450, Los Angeles, CA 90067 310.203.4800 | Fax: 310.203.4850 >> NEW JERSEY Newark: 744 Broad Street, Suite 1510, Newark, NJ 07102 973.848.2900 | Fax: 973.623.0405 >> NEW YORK One Penn Plaza, Suite 4701, New York, NY 10119 646.833.0900 | Fax: 646.833.0877 >> OTHER ILLINOIS Bolingbrook: 305 West Briarcliff Road, Suite 201, Bolingbrook, IL 60440 630.759.0800 | Fax: 630.759.8504 Park Ridge: 22 South Washington Avenue, Park Ridge, IL 60068 847.268.8600 | Fax: 847.268.8614 This newsletter is for general information only and is not intended to provide and should not be relied upon for legal advice in any particular circumstance or fact situation. The reader is advised to consult with an attorney to address any particular circumstance or fact situation. The opinions expressed in this newsletter are those of the author and not necessarily those of Tressler LLP or its clients. This bulletin or some of its content may be considered advertising under the applicable rules of the Supreme Court of Illinois, the courts in New York and those in certain other states. For purposes of compliance with New York State Bar rules, our headquarters are Tressler LLP, 233 S Wacker Drive, 22nd Floor, Chicago, IL 60606, 312.627.4000. Prior results described herein do not guarantee a similar outcome. The information contained in this newsletter may or may not reflect the most current legal developments. The articles are not updated subsequent to their inclusion in the newsletter when published. | Copyright © 2015 CALIFORNIA | ILLINOIS | NEW JERSEY | NEW YORK CLICK HERE to add yourself or a friend to our email list FOLLOW US ON TWITTER Get the latest news and special events happening at Tressler LLP!