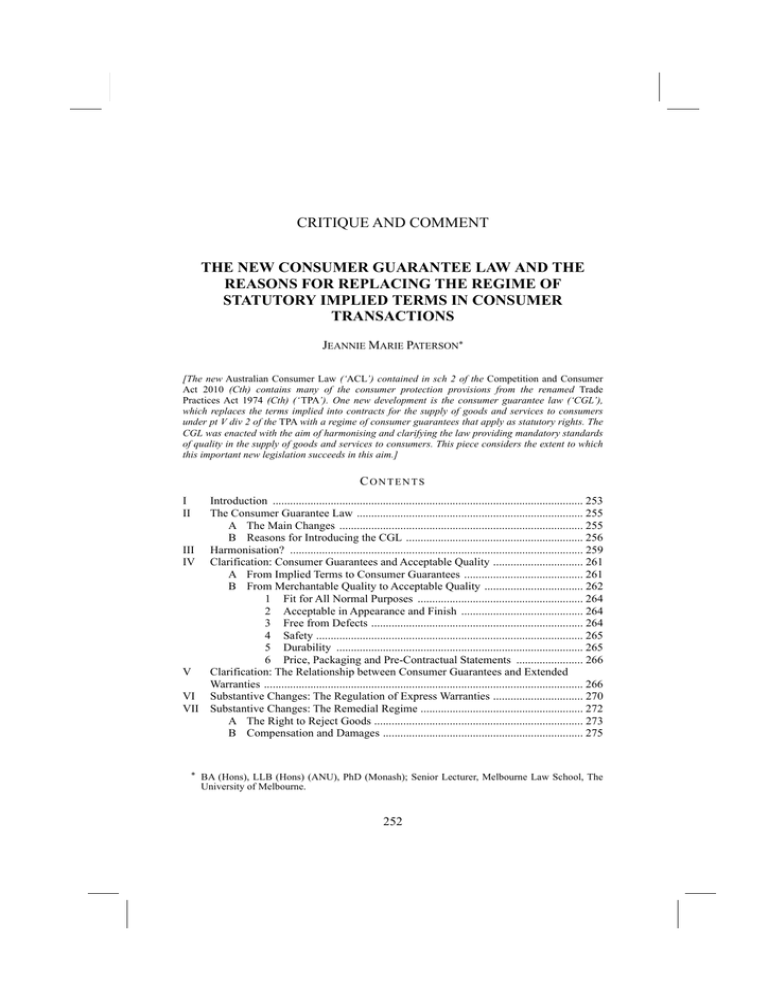

The New Consumer Guarantee Law and the Reasons for Replacing

advertisement