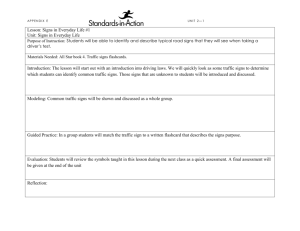

Everyday

advertisement