Critical Study of the Truth in Negotiating Law

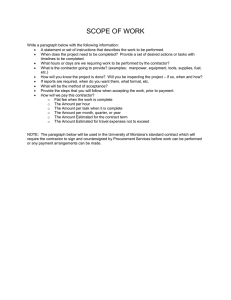

advertisement