Litigating Privacy and Data Breach Issues in 2014

Mobile Device Security

Lucy Thomson

Livingston PLLC

Washington, DC

Robert Thibadeau

Livingston PLLC

Washington, DC

Reprinted with Permission

Mobile

Device

Security

By Robert Thibadeau and Lucy L. Thomson

A

s the use of mobile devices

explodes around the globe,1

concerns about the security of

data and communications on mobile

devices are increasing. Data breaches

are occurring with alarming frequency

throughout the mobile device environment, in all industry sectors, among all

types of companies large and small, and

among governments around the globe.2

In 2012 through mid-2013, the loss or

theft of 132 mobile devices resulted in

exposure of more than 2,680,000 personal records.

In addition to personal records, security failures related to mobile devices

have also exposed confidential communications, intellectual property, and

other sensitive business information.

The harm to individuals and organizations can be extensive, including fraud,

identity theft, and a multiplicity of

breakdowns in data protection such as

data theft, privacy violations, and spying. As mobile devices are increasingly

employed for payments and electronic

health records, theft of money, goods,

services, and the most sensitive personal

health records will become more

frequent.

Of particular concern for lawyers

are the large volumes of sensitive and

confidential data they increasingly

store on their mobile devices—

information subject to the attorneyclient privilege; client trade secrets;

records that are sealed or under a protective order; classified data; grand jury

records; and many other types of sensitive data, including personal, financial,

health care, and law enforcement

records. As the use of mobile devices

continues to grow, the likelihood of

breaches involving such data becomes

more certain.

Lawyers have a responsibility to

make sure that the mobile devices they

use for confidential communications

are secure.3 At the same time, lawyers

should counsel their clients regarding

the need to adopt security best practices throughout their organizations.

As information becomes the primary

means of production, and institutions

forge ahead to adopt sweeping changes

based on mobile technologies, the risks

underlying this mobile transformation

are legion and not well understood. All

of these developments have profound

implications for the law.

Some mobile breaches are the

result of vulnerabilities in the design

and configuration of mobile devices.

In other cases, hackers have inserted

malware (malicious code) into applications (apps) so when users download

them onto mobile devices, the malware allows hackers to gain access to

sensitive information. Some malware

can subvert search results and redirect users to a web page where they

are encouraged to download additional malware, while other malware

can cause users’ personal information to be publicly disclosed without

their knowledge. Hackers can intercept

unencrypted data as it is transmitted

to and from mobile devices. The vulnerabilities are particularly serious if

the mobile devices are used to communicate with legal clients by email

or through social media, or to view,

process, or store confidential data and

information.

Published in The SciTech Lawyer, Volume 9, Special Issue, Summer 2013. © 2013 American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may

not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

Mobile Device Security

Computer security technology is

fundamentally about “information isolation” and the controls over access to

that information. A common example

of an information isolation mechanism

is the user name and password typically

used for logging in, but any modern

operating system such as Windows,

iOS, or Android has literally hundreds

of thousands of fine-grained access

controls in every copy. These controls

are set by policies, and security fails

when policy-governed isolation fails.

To effectively seal the cracks

between technology and law, it would

be better if there were some minimal

isolation guarantees that could be uniformly assumed by the laws. These are

ultimately the subject of policies set by

manufacturers, application providers

(app providers), telephone companies (telcos), IT managers (IT), and

personal good practices. To fully appreciate how so much can go wrong in

mobile device security, it is important

to understand the fundamental classes

of security defects (attack surfaces) and

what security measures already exist

to mitigate them. These attack surfaces

encompass the device itself, the operating system (OS) on the device, and

external service providers such as app

providers, telcos, and IT.

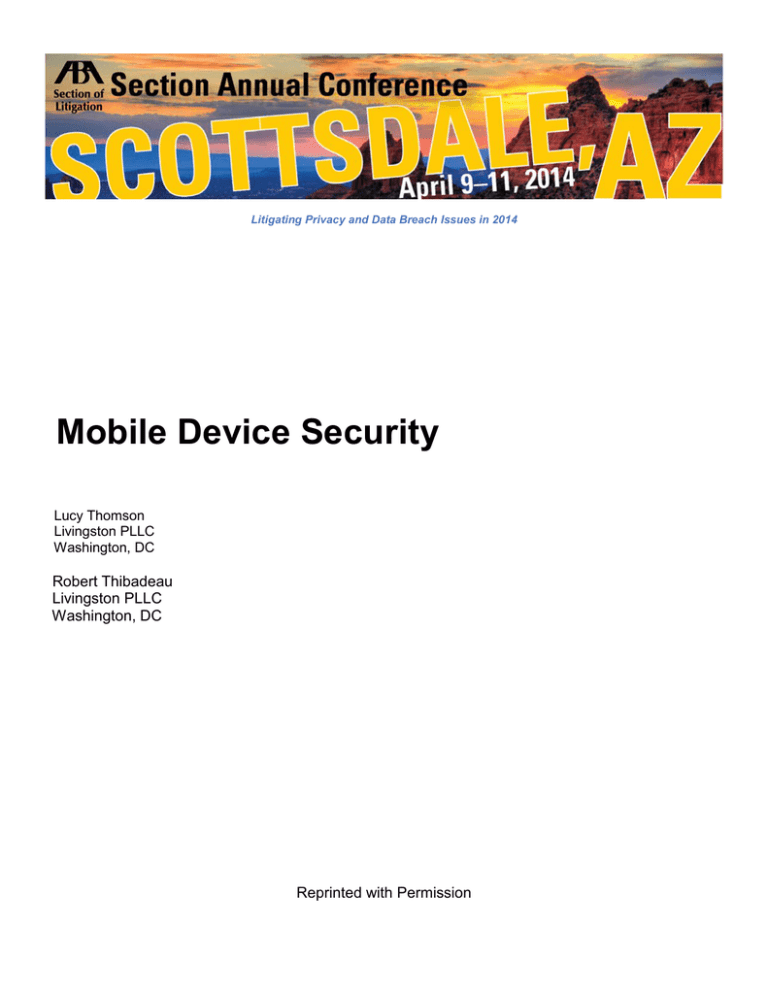

Figure 1 (below) shows how security architects categorize defects in

the mobile device ecosystem. This

approach can help in determining who

did what in a potential negligence case.

For each attack surface, the diagram provides examples of attack

vectors with some of the common

attacks on, or other failures of, generally accepted good security policy.

The device may be stolen, the data on

it may be stolen, and various sensors

such as cameras and microphones may

be surreptitiously turned on. The OS

itself may be faulty (as illustrated in

the FTC-HTC case discussed below),

preboot Trojans (malware that affects

preboot operations) may “jail break”4

the OS protections, or the OS may

permit weak passwords. Provider failures include failure of IT management

(policies to manage mobile devices

remotely, as discussed below), as well as

malicious app injection and data theft

FIGURE 1

Attack Surfaces & Vectors

for mobile devices

DATA-AT-REST

ATTACKS

POOR

PASSWORDS

DEVICE

THEFT

DEVICE

MISUSE OF

CAMERA,

MIC, GPS,

ETC.

ATTACK

SURFACES

PREBOOT

TROJANS

ALTER OS

OS

PROVIDERS

FAULTY OS

(FTC-HTC)

MALICIOUS

APP

INJECTION

IT POLICY

FAILURE

ID THEFT

(as in the FTC’s Frostwire case). These

are only a few of the hundreds of failures that can occur across these attack

surfaces.

App Vulnerabilities

The huge ecosystem of apps—well

over 1.5 million and growing—creates

additional security issues that differ from those involving the security

architecture of mobile devices and OS

themselves.5 Many of the apps are made

available through official stores or markets, such as the Apple iTunes store,

some Android markets, and the Microsoft Store, where strict controls are

exercised to help ensure that the apps

do not violate accepted security practices. Apps are also available through

unofficial sources, particularly in the

Android world.

Malicious apps are often attack vectors that pierce the device, OS, and

provider attack surfaces depicted in Figure 1. They create causal event paths that

memorialize an actual attack or security

failure and show where culpability lies.

For example, the FBI recently issued

a warning about malware that attacks

Android OS for mobile devices and

lures users to compromise their mobile

devices.6 For example:

• Loozfon malware contains

advertisements for work opportunities with a link to a website

designed to push the malware to

a user’s mobile device; once on

the mobile device, the malicious

software uses an OS weakness

to steal contact details from the

user’s address book.

• FinFisher malware can take over

the components of a mobile

device and remotely control and

monitor it. The malware is transmitted to a smartphone when the

user visits a specific web link or

opens a text message masquerading as a system update.

A company that provides security

protection analyzed more than 400,000

apps (60 percent) in Android’s official

Google Play marketplace (as of September 2012) and classified 25 percent

Published in The SciTech Lawyer, Volume 9, Special Issue, Summer 2013. © 2013 American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may

not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

of the apps as “suspicious” or “questionable,” based on the permissions

requested, categorization of the app,

user rating, number of downloads, and

reputation of the publisher.7 The report

concluded that Android’s open framework has made it the primary target of

hackers, who lure unsuspecting users

to download their apps and end up

exposing the users’ organizations to

significant security risks.

Legal Issues

As mobile devices become essential for

individual communication and global

ecommerce, sensitive data and information must be protected. Two cases

involving the security of mobile devices

and apps have already been brought

by the US Federal Trade Commission

(FTC).

In one case settled by the FTC (as

announced on February 22, 2013),

Protect Your Mobile Device and Data

FBI Recommendations

• When purchasing a smartphone, know the features of the device, including the

default settings. Turn off unnecessary features to minimize the attack surface

of the device.

• Depending on the type of phone, the OS may offer encryption, which can be

used to protect the user’s personal data in case of loss or theft.

• Consult reviews of the developer/company who published the app.

• Review and understand the permissions you are giving when you download

apps.

• Passcode protect your mobile device, and enable the screen lock feature after

a few minutes of inactivity. This is the first layer of physical security to protect

the contents of the device.

• Obtain malware protection for your mobile device. Look for applications that

specialize in antivirus or file integrity to help protect your device from rogue

applications and malware.

• Be aware of applications that enable geolocation, which will track the user’s

location anywhere and can be used for marketing and by malicious actors (e.g.,

stalkers and/or burglars).

• Jail break or rooting is used to remove certain restrictions imposed by the

device manufacturer or cell phone carrier and allows the user nearly unregulated control over what programs can be installed and how the device can be

used. At the same time, however, jail breaking often involves exploiting significant security vulnerabilities and increases the attack surface of the device. Any

time an application or service runs in “unrestricted” or “system” level within an

OS, it allows any compromise to take full control of the device.

• Do not allow your device to connect to unknown wireless networks, which

could be rogue access points that capture information passed between your

device and a legitimate server.

• If you decide to sell your device or trade it in, make sure you wipe the device

(reset it to factory default) to avoid leaving personal data on the device.

• Smartphones require updates to run applications and firmware; without these,

the risk of the device being hacked or compromised increases.

• Avoid clicking on or otherwise downloading software or links from unknown

sources.

• Use the same procedures on your mobile phone as you would on your computer when using the Internet.

the FTC had charged that millions of

Android smartphones were manufactured by HTC America (a leading

mobile device manufacturer) with

insufficient security controls, which

compromised sensitive device functionality, potentially permitting malicious

applications to send text messages,

record audio, and even install additional

malware onto a consumer’s device, all

without the user’s knowledge or consent. The FTC alleged that malware

placed on consumers’ devices without

their permission could be used to record

and transmit information entered into

or stored on the device, including, for

example, financial account numbers and

related access codes or medical information. Malicious applications could

also gain unauthorized access to a variety of other sensitive information, such

as a user’s geolocation information and

the contents of a user’s text messages.

The complaint also alleged that HTC

America failed to provide its engineering staff with adequate security training,

review or test the software on its mobile

devices for potential security vulnerabilities, follow well-known and commonly

accepted secure coding practices, and

establish a process for receiving and

addressing vulnerability reports from

third parties.8

In 2011, the FTC charged that an

app developer, FrostWire LLC, had

engaged in unfair and deceptive practices by: (1) configuring the default

settings of a peer-to-peer (P2P)9 filesharing app so that it publicly exposed,

upon installation and set-up on the

user’s smartphone or tablet, a wide

range of personal information (including photos, videos, documents, and

other files) without the user’s authorization; and (2) misleading users about

the extent to which downloaded files

would be distributed with the P2P filesharing network. On October 11, 2011,

it was announced that Frostwire had

agreed to settle FTC charges that its

software (e.g., FrostWire for Android)

likely would cause consumers unwittingly to expose sensitive personal files

stored on their mobile devices, and

that it misled consumers about which

downloaded files from their desktop

Published in The SciTech Lawyer, Volume 9, Special Issue, Summer 2013. © 2013 American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may

not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

and laptop computers would be shared

with a file-sharing network. The settlement bars Frostwire from using default

settings that share consumers’ files,

requires it to provide free upgrades to

correct the unintended sharing, and

bars misrepresentations about what files

its applications will share.10

Mobile Security Standard

The legal standard for mobile security

increasingly needs careful examination.

Although only a handful of judicial

decisions specifically address the issue

of information security, other key

cases set forth relevant principles when

assessing security practices and possible negligence by organizations that fail

to implement appropriate security and

subsequently suffer a security breach.

Recall the well-known T.J. Hooper

case11 in which two tugboats were ruled

unseaworthy and liable for damages

to the cargo because they did not have

radio receivers to receive storm warnings. The T.J. Hooper case held that a boat

can be deemed unseaworthy if it is not

equipped with a well-known, generally

accepted practice of ensuring safety—in

that case, a radio. Similarly, smartphones

and tablets need to be deemed worthy of

use, particularly when proper security is

already widely available today and best

practice standards exist that can make

mobile devices quite secure against many

possible attacks.

Robert Thibadeau, Ph.D., is Senior

Vice President and Chief Scientist at

Wave Systems, an adjunct professor

in the School of Computer Science at

Carnegie Mellon (teaching computer

security since 1996), and a contributing

author on encryption to the ABA book

titled Data Breach and Encryption

Handbook (2011). He can be reached

at rthibadeau@wave.com. Lucy L.

Thomson is principal of Livingston

PLLC, a Washington, DC, law firm

(which focuses on law and technology,

particularly cybersecurity and global

data privacy), Chair of the ABA Section

of Science & Technology Law, and editor

of the Data Breach and Encryption

Handbook (2011). She can be reached at

lucythomson.scitech@mindspring.com.

The foreseeability of a potential

harm is also a key factor. Nash v Port

Auth. of N.Y. & N.J.12 discusses this

issue in the context of the 1993 terrorist truck bombing of the World Trade

Center (WTC). In this case, experts

had warned that the public garage

under the WTC posed a security risk,

but the landlord had failed to take steps

to address that risk. In a lawsuit and

trial following the bombing, the jury

found that the defendant Port Authority was negligent. In affirming the case

on appeal, the court discussed the standard of reasonable care and stated:

“there are circumstances in which the

nature and likelihood of a foreseeable

security breach and its consequences

will require heightened precautions

[above minimal precautions].”

The duty to reasonably secure a

mobile device or network against foreseeable intrusions (e.g., a hacker attack)

depends on the nature of the risk as

well as the burden of minimizing the

risk. An enforceable duty can be found

under the common law (negligence,

breach of contract, breach of fiduciary

duty, etc.) and in state statutes, such as

consumer protection and data security laws (e.g., Massachusetts, Nevada,

Maryland, and New Jersey include a

duty to provide information security to

protect personal information).13

In the case of a breach, questions

would be asked about whether the organization potentially responsible for

securing the device (e.g., the manufacturer of the device, OS developer,

provider, or user) took reasonable steps

to minimize the risk—e.g., whether

it conducted a risk assessment, determined the likelihood of a breach, and

assessed the adequacy of the security that was adopted. Based on such a

risk assessment, appropriate security

controls should then be selected, implemented, and continuously monitored so

that risks and vulnerabilities are reduced

to a reasonable and appropriate level.

What Steps Must Be Taken to

Provide Appropriate Security for

Mobile Devices?

Developing a plan for appropriate security begins with a risk assessment. The

purpose of the risk assessment is to

inform decision makers and support

risk responses by identifying:

1. relevant threats to the organization, or threats directed through

other organizations against them,

via the mobile device;

2. vulnerabilities of the mobile

device both internal and external

to the organization;

3. impact (i.e., harm) to the organization that may occur given the

potential for threats exploiting

vulnerabilities; and

4. likelihood that harm will occur.

The end result is a determination of

risk, which is typically a function of the

degree of harm and the likelihood of

harm occurring.

Participants who use mobile devices

for key transactions, or to process or

store sensitive and confidential information, should take reasonable steps

to minimize the risks. To prevent data

breaches, it is essential to analyze and

understand the root causes of security

failures and develop a specific plan to

address them.

Security Architecture

The security architecture for modern mobile devices, which all have the

same main properties, is strong. If the

security architecture is implemented

and managed properly, many potential

threats will be eliminated. The remaining threats are insider attacks and the

failure of users to follow good security

practices.

Security Policy

The vast majority of attacks and security failures are due to failed security

policies. The good news is that organizations can nearly eliminate breaches of

mobile devices if they take a prioritized

approach that adopts and enforces

good security practices.

Information security policy is an

aggregate of directives, rules, and

practices that prescribes how an organization manages, protects, and

distributes information.14 It is particularly important for organizations to

Published in The SciTech Lawyer, Volume 9, Special Issue, Summer 2013. © 2013 American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may

not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.

adopt security policies that let users

know the expectations for the use of

their mobile devices and the rules they

must follow to keep their information systems secure. Security policy

should address the fundamentals of the

organization’s governance structure,

including:

• information security roles and

responsibilities;

• statement of security controls

baseline and rules for exceeding

the baseline; and

• rules of behavior that users are

expected to follow and consequences for noncompliance.

It is important that organizations

adopt a “culture of security” in which

all employees and business/outsourcing

partners consider themselves responsible for the security of the organization.

Basic policies must be enforced

and should require strong passwords

and require encryption of data, permit

remote locate/wipe capability, and limit

apps that can be put on the phone.

User security education is equally critical—when installing apps, many users

routinely click “yes” without considering the nature of the permissions they

are granting. Hackers exploit this lack

of awareness by building malware that

exploits the permissions the user has

given, creating easy access for them to

steal data from mobile devices.

Furthermore, the use of mobile

devices does not occur in a vacuum.

Although sensitive data such as authentication credentials (user names and

passwords), client email, encryption

keys, contacts, and so on are often

stored directly on a mobile device,

such data and information may also

be transmitted to the cloud after being

created or processed on a mobile

device. Use of a cloud provider introduces further security and privacy risks

that must be addressed.15

Conclusion

How mobile devices are configured and

used affects the security of sensitive

data just as much as the security technology on the devices. With so many

The vast majority

of attacks and

security failures

are due to failed

security policies.

mobile devices on networks today, participants in the mobile device ecosystem

must adopt and enforce effective security policies and procedures that protect

sensitive and confidential data and other

information the organization creates,

collects, stores, and transmits on mobile

devices. The failure to secure sensitive data can expose an organization to

unacceptable risks and result in enormous liability in the event of a breach. u

Endnotes

1. Mobile devices are the fastest-growing computing technology. As of 2012, 87%

of American adults owned a cell phone,

45% owned a smartphone, and 31% owned

a tablet. By the end of 2013, the number of

mobile-connected devices will exceed the

number of people on earth, and by 2017 it is

expected that there will be nearly 1.4 mobile

devices per capita. Pew Research Center

(Washington, D.C. 2013), available at http://

pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/

February/Pew-Internet-Mobile.aspx.

2. Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC),

http://www.idtheftcenter.org.

3. The Model Ethics 20/20 Rules adopted

by the American Bar Association (2012)

explicitly require that lawyers provide “competent representation” by keeping abreast of

changes in the law and its practice, including the “benefits and risks associated with

relevant technology” (Rule 1.1). To protect

the confidentiality of information, a lawyer

shall make “reasonable efforts to prevent the

inadvertent or unauthorized disclosure of, or

unauthorized access to, information relating

to the representation of a client” (Rule 1.6).

4. Jail breaking entails installing software

on a phone to “break open” the phone’s OS

security and allow a user to modify anything

it protects, including limits on apps that can

be loaded on the device. This is a well-known

form of “privilege escalation” that usurps OS

isolation assumptions and thus weakens the

device’s security.

5. As of October 2012, the apps available

for Android phones and for Apple mobile

devices numbered about 700,000 each, while

Microsoft had 120,000 apps. Shara Tibken,

“Google Ties Apple with 700,000 Android

Apps” (10/30/12), available at http://news.

cnet.com/8301-1035_3-57542502-94/googleties-apple-with-700000-android-apps/.

6. Smartphone Users Should Be Aware

of Malware Targeting Mobile Devices and

Safety Measures to Help Avoid Compromise

(Oct. 12, 2012), available at http://www.fbi.

gov/scams-safety/e-scams/e-scams.

7. Bit9 Report, Pausing Google Play:

More Than 100,000 Android Apps May Pose

Security Risks With Mobile Security Survey,

available at https://www.bit9.com/download/

reports/Pausing-Google-Play-October2012.

pdf.

8. See the complaint and settlement agreement at http://www.ftc.gov/

opa/2013/02/htc.shtm.

9. P2P enables computers to form a network and share digital files (music, video,

and documents), play games, and facilitate online telephone conversations such as

Skype directly with other computers on the

network.

10. See the complaint and settlement

agreement at http://ftc.gov/opa/2011/10/

frostwire.shtm.

11. 60 F .2d 737 (2d Cir. 1932).

12. 51 A.D.3d 337, 856 N.Y.S.2d 583

(2008).

13. See Arthur E. Peabody, Jr. and Renee

A. Abbott, The Aftermath of Data Breaches:

Potential Liability and Damages, in Data

Breach and Encryption Handbook

(2011), chapter 3.

14. See Information Security Handbook: A Guide for Managers, NIST SP

800-100 (2007), available at http://csrc.nist.

gov/publications/nistpubs/800-100/SP800100-Mar07-2007.pdf.

15. See Guidelines on Security and

Privacy in Public Cloud Computing,

NIST SP 800-144 (2011).

Published in The SciTech Lawyer, Volume 9, Special Issue, Summer 2013. © 2013 American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may

not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association.