Organizational Failure: A critique of recent

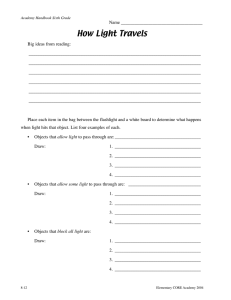

advertisement