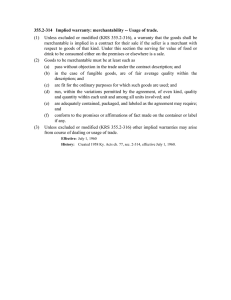

Disclaimers of Implied Warranty in the Sale of New Homes

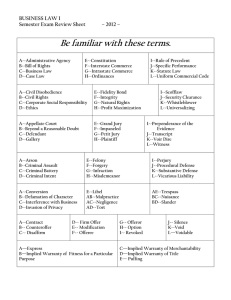

advertisement