Developing Kindergarten Readiness and Other Large

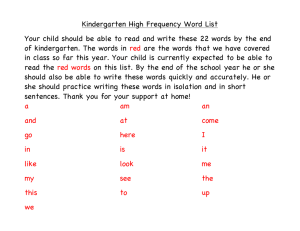

advertisement