Scholarship in Public: Knowledge Creation and Tenure Policy in the

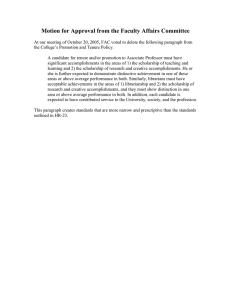

advertisement