A Case for Inclusive Education - Toronto District School Board

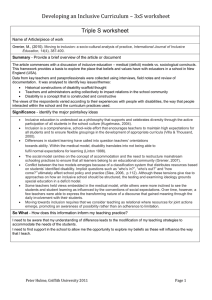

advertisement