A Detachable Transformer

advertisement

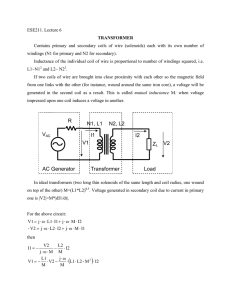

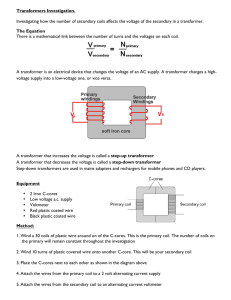

A Detachable Transformer with Microfabricated Secondary Coil for Powering MEMS Devices Jie Wua, Victor Quinnb, and Gary H. Bernsteina a. Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Univ. of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556 b. Tabtronics, Inc., Geneseo, NY 14454, USA. Over the past two decades, microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) has evolved into a new discipline1. As much progress has been achieved in fabricating discrete MEMS devices, complete systems-on-a-chip start to take form. It is desirable to develop a method to release MEMS chips from power supply tethering in order to give them some degree of autonomy, and allow implantation of devices in biomedical or other applications. This paper explores the feasibility of inductively powering microsystems to decrease their overall size, increase their available energy budget, and free them from mechanical and electrical contacts. One conventional on-chip powering scheme is the use of electrochemical cells, such as batteries, but these suffer from limited storage capacity and lifetime2, 3. Regenerating on-chip powering schemes, such as scavenging energy from environmental vibrations4, 5, 6 and implementing thermopiles7 or solar cell arrays8, 9, cannot provide adequate voltage or power for many MEMS devices. In comparison, inductively coupling power onto the chip combines the advantages of no physical connections, no moving parts, high reliability and efficiency, fabrication compatibility with Si integrated circuits (IC) and ease of packaging. Here we report a prototype detachable transformer of which the secondary coil is fabricated by IC techniques on a silicon chip. The conventionally wound transformer primary utilizes a ferrite core to provide magnetic field concentration in a 2 mm air gap. When the secondary is inserted into this air gap, energy is transferred from the primary coil to the secondary coil as a result of magnetic flux linkage, freeing the MEMS device and secondary circuit from hard wired connections. Compared with wire-wound coils, microfabricated coils on silicon substrates suffer from much more pronounced design limits and parasitic effects, such as low inductances from finite turn numbers, large internal resistance from small coil cross-sectional area and parasitic capacitance from conductive Si substrate and proximity of metal lines. Detachable transformers with microfabricated secondary coils have already been demonstrated10, 11, 12, but these efforts targeted low power/voltage applications with little analysis of coupling coefficient and parasitic effects. -1- Fig. 1 Three transformer configurations. From left to right: primary on the large arm, on the small arm and split primary. The detachable construction results in a significantly reduced coupling coefficient when compared to the coupling coefficients of conventional transformers. This paper considers calculations and measurements to characterize the operation of this detachable transformer. It should be noted that the analysis methods for low coupling coefficients can be applied to implantable applications and others where the environmental conditions or application specifications limit primary and secondary coupling intimacy. A square “C” core with a 2 mm air gap was used to concentrate the magnetic flux. It is made from Philips 3F3, with side lengths of 40 and 50 mm and a cross-sectional area of 8x8 mm2. To obtain a more general understanding of detachable transformers with microfabricated secondaries, three configurations were used for simulations and experiments, as shown in Fig. 1 with variations of the relative positions between two coils. The secondary coil was designed as a square spiral microcoil with average side length of 12 mm, as shown in Fig. 2(a). Processing involved electron-beam evaporation of a 1.2 µm thick layer of copper on an oxidized silicon wafer, and patterning by liftoff. The coil had 10 turns and the metal traces were 80 µm wide on a 100 µm pitch. The substrate was left floating. The secondary coil impedance was measured using an Agilent 4294A impedance analyzer over the frequency range from 40 Hz to 110 MHz. The model shown in Fig. 2(b) was used to extract lumped elements. A comparison of measured coil impedance with calculated values from the model is given in Fig. 2(c) with L = 3.4 µH, R = 95.5 Ω, and C = 76 pF. The self-resonant frequency of the secondary coil with air core is around 10 MHz. The primary coil experiences different parasitic effects from those of the secondary coil. Because the secondary coil is built on a conductive silicon substrate, eddy currents are induced in the chip when the secondary is inserted in the gap. As a result, the primary inductance decreases and energy loss increases. To illustrate the effects of the silicon substrate, the impedance of a 20-turn split primary coil were measured from 40 Hz to 110 MHz with and without the chip in the air gap. A bare silicon wafer was used instead of one with microfabricated coil to avoid the -2- complexity from additional reflected secondary impedances. A comparison of the two measurements indicates an increased energy loss and reduced primary inductance from the inserted Si chip. Fig. 2 (a) Micrograph, (b) equivalent circuit and (c) impedance of microfabricated coil. The parasitic effects of the microfabricated coil must be considered when evaluating the coupling coefficient. One popular method of obtaining k is to measure the inductances of one coil with the other one first open-circuited (L1) then short-circuited (LLEAK). The difference in coil inductances between the two measurements is the coil magnetizing inductance, which is expressed as LMAG = k 2 L1 . Therefore k = LMAG L1 = (L1 − LLEAK ) L1 . However, for our detachable transformer, when the inductances are measured from the primary, the short-circuit condition of the secondary cannot be satisfied due to non-negligible parasitics, which are equivalent to the load. To minimize the effect of parasitics, the coupling coefficient is obtained by measuring the inductances of the secondary coil with the primary coil open and then shorted. The first set of measurements yields k values for the three transformer configurations corresponding to Fig. 1. As expected, Figure 3 shows that the split primary provides the highest value of coupling coefficient, and the primary on the large arm provides the least. The coupling coefficients show frequency dependence, and drop rapidly at higher frequencies. This drop is caused by parasitic capacitances shunting the secondary inductance. Strictly speaking, accurate inductance values can be measured only when the coil parasitic capacitance does not noticeably affect the total impedance. Therefore, our measurements are subject to greater -3- errors at high frequency owing to increased internal secondary capacitive loading. However, the capacitive susceptance at lower frequencies is small enough to be neglected, and the obtained k values in this range are valid. The coupling coefficients taken at the lower end of the curves are 0.41, 0.73 and 0.79 for the primary on the large arm, primary on the small arm and split primary, respectively. The effect of secondary parasitics can be removed by curve-fitting the measured secondary impedances using the model of Fig. 2(b), since the inductances of secondary coil with the primary coil open or shorted can be extracted. ( ) The inductance in the model should be L2 when the primary is open-circuited, and LLEAK = 1 − k 2 L2 when the primary is short-circuited. From the curve fitting, the coil inductances are determined as 7.6 µH, 6.2 µH, 3.7 µH and 3.0 µH, respectively, which leads to coupling coefficients of 0.429, 0.716 and 0.778, respectively. Coupling coefficients obtained by curve-fitting are close to those values taken at low frequency in Fig. 3, thus supporting both strategies for measuring coupling coefficients. The above measurements demonstrate parameters for detachable microfabricated coils. A coupled magnetic circuit model can be used to develop an analytical prediction of transformer voltage gain when secondary distributed capacitive impedance is much less than the load impedance: Fig. 3 Measured coupling coefficients for three different primary placements. -4- Gv = k L2 1 . ⋅ 2 2 L1 1 − ω 1 − k L2 C 2 + jωC 2 R2 ( ) (1) Here R2 and C2 are secondary resistance and distributed capacitance respectively. In comparison, the popular equivalent circuit model, using a lumped equivalent representation of leakage inductance, predicts the following voltage gain: Gv = N2 1 ⋅ . 2 N 1 2 − k (1 + jωC 2 R2 ) − ω 2 1 − k 2 C 2 L1 (N 2 N 1 )2 ( ) ( ) (2) Here N1 and N2 are the primary and secondary turns respectively. This transfer function from the equivalent circuit model is inaccurate, particularly at low coupling coefficients which characterize detachable transformer configurations. Henceforth, our analytical predictions will utilize the voltage gain as derived from the coupled magnetic circuit model (1). At low frequencies, the open circuit voltage ratio of the transformer is expressed as V2 V1 = k L2 L1 . At higher frequencies, the voltage gain is strongly influenced by the resonance between the parasitic capacitance and the leakage inductance. Figure 4 shows the voltage ratio for transformers with 8- and 10- turns split primary and the secondary open. The voltage ratio remains constant up to 1 MHz, then rises rapidly and peaks between 9 ~ 10 MHz, GV (with open-circuited secondary) 3.0 2.5 3.0 8/10 transformer Measurement Calculated from Eqn. 1 Simulated with MicroCap 7 10/10 transformer Measurement Calculated from Eqn. 1 2.5 Simulated with MicroCap 7 2.0 2.0 1.5 1.5 1.0 1.0 0.5 0.5 0.0 10k 100k 1M 10M Frequency (Hz) 0.0 10k 100k 1M 10M Frequency (Hz) (a) (b) Fig. 4 The frequency property of transformer voltage gain with open-circuit secondary. (a) 8/10 and (b) 10/10 transformer (transformers with 8 or 10-turn primary and 10-turn secondary). -5- decreasing sharply at higher frequencies. Using the parasitic elements derived from Fig. 2(b) with the coupling coefficient, the transformer voltage ratio as a function of frequency was also simulated using a circuit simulation software – Micro-Cap 7 [13] (The inductance of 10-turn split primary is 5.5 µH). The simulation results are plotted in Fig. 4 along with measurement and calculation results using eqn. (1). All three data sets show voltage amplification as a result of a series resonance of internal secondary parasitic capacitance and leakage inductance. The agreements also support the validity of our characterization methods. Since the project goal is to develop an on-chip powering scheme accommodating the special power requirements of MEMS devices, it is relevant to demonstrate the versatility of our prototype transformer. For the transformer with the 10-turn split primary, 223.4 Vpp was obtained from the open-circuited secondary with an impressed primary voltage of 253.1 Vpp at 744.9 kHz. The voltage ratio was still governed by transformer theory at this frequency. (Higher frequency performance was not shown because of the limitation of the amplifier.) Such a voltage is appropriate for the operation of such MEMS devices as electrokinetic micropumps, electrostatic microactuators and many other devices, especially if integrated with a simple half- or full-wave rectifier bridge, with or without filtering or regulation [14]. In addition, we have demonstrated 8.11 Wave of power delivered to a 100 Ω load. It can be concluded that the prototype transformer is capable of generating usably high voltage and power for applications in MEMS systems. Additionally, analytical techniques have been developed to accurately model transfer function in the presence of large parasitics and when a low coupling coefficient cannot be avoided. All the measurements were done with high-resistance, thin-film secondary coils, yet the transformer has already demonstrated sufficient voltage and power capability for MEMS applications. With the adoption of more advanced processes, e.g. deep reactive ion etching and electroplating, it is projected that the transformer performance can be further improved through a significant decrease in internal resistance, as well as possible back-side placement to conserve chip real estate. This work is currently under way. REFERENCES: [1] R. P. Feynman, “There is plenty of room at the bottom,” J. Microelectromech. Syst., vol. 1, pp. 60 – 66, 1992. [2] M. Madou, Fundamentals of Microfabrication. CRC press LLC, 1997, Chapter 9. [3] P. B. Koeneman, I. J. Busch-Vishniac, and K. L. Wood, “Feasibility of micropower supplies for MEMS,” J. Microelectromech. Syst., vol. 6, pp. 355-362, 1997. -6- [4] C. B. Williams and R. B. Yates, “Analysis of a micro-electric generator for microsystems,” Sensors and Actuators A, vol. 52, pp. 8-11, 1996. [5] J. Mullins, “Micro supplies to power MEMS devices,” IEEE Spectrum, pp. 23 – 24, Sept. 2001. [6] M. El-hami, P. Glynne-Jones, N. M. White, M. Hill, S. Beeby, E. James, A. D. Brown, and J. N. Ross, “Design and Fabrication of a new vibration-based elecromechanical power generator,” Sensors and Actuators A, vol. 92, pp. 335-342, 2001. [7] W. Qu, M. Ploetner, and W. Fischer, “Microfabrication of thermoelectric generators on flexible foil substrates as a power source for autonomous microsystems,” J. Micromech. Microeng., vol. 11, pp.146 – 152, 2001. [8] J. B. Lee, Z. Chen, M. G. Allen, A. Rohatgi, and R. Arya, “A miniaturized high voltage solar cell array as an electrostatic MEMS power supply,” J. Microelectromech. Syst., vol. 4, pp. 102 – 108, 1995. [9] T. Salalibara, H. Izu, T. Kura, W. Shinohara, H. Iwata, S. Kiyama, and S. Tsuda, “High-voltage photovoltaic microdevices fabricated by a new laser-processing,” Proc. IEEE MEMS ’95, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 282 –287. [10] D. Dudenbostel, K. Krieger, C. Candler, and R. Laur, “A new passive CMOS telemetry chip to receive power and transmit data for a wide range of sensor applications,” TRANSDUCERS ’97, Chicago, pp. 995 – 998. [11] J. A. Von Arx and K. Najafi, “On-chip coils with integrated cores for remote inductive powering of integrated microsystems,” TRANSDUCERS ’97, Chicago, pp. 999 – 1002. [12] S. Takeuchi, N. Futai, and I. Shimoyama, “Selective drive of electrostatic actuators using remote inductive powering,” MEMS 2001 – 14th IEEE Int’l Conf. MEMS, 2001, Interlaken, Switzerland, pp.574 – 577. [13] www.spectrumsoft.com. [14] M. Mino, T. Yachi, A. Tago, K. Yanagiawa, and K. Sakakibara, “Microtransformer with monolithically-integrated rectifier diodes for micro-switching converters,” 24th Annu. Power Electron. Spec. Conf., 1993, pp. 503 – 508. -7-