NZ Sectors Report

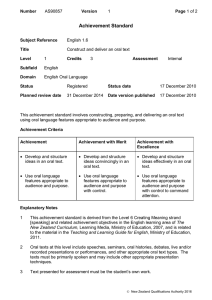

advertisement