Academic Writing Guide - Victoria University of Wellington

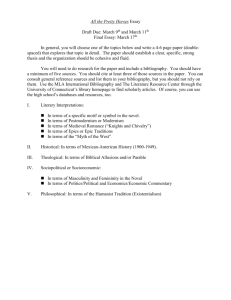

advertisement