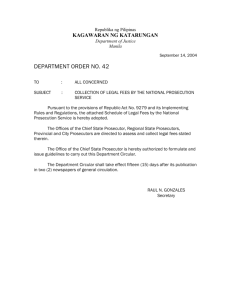

Delegation of the Criminal Prosecution Function to Private Actors

advertisement