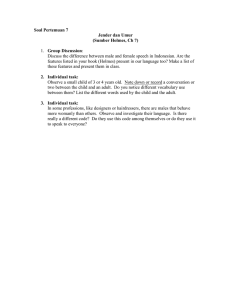

Finding the Good in Holmes`s Bad Man

advertisement