1 In This Issue - Council for Learning Disabilities

advertisement

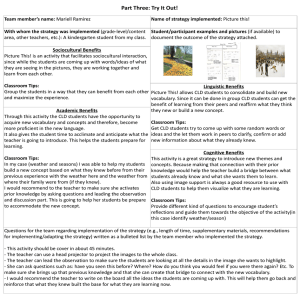

C OUNCIL FOR L EARNING D ISABILITIES LD Forum A Publication of the Council for Learning Disabilities February/April 2012 President’s Message of the Year Awards. Additional information and nomination forms can be found in this issue and on cldinternational.org. Applications are also being accepted for the Outstanding Researcher Award. Each year, CLD recognizes the scholarly achievement of early career researchers. Applicants are invited to submit a manuscript based on a dissertation that was completed within the past 5 years. In addition to receiving a plaque at the CLD conference, the winner’s manuscript will be considered for publication in Learning Disability Quarterly. In this issue you will find information on the Leadership Academy for 2012. We will have six new Academy Leaders and six new Mentors for the fall 2012 cohort. I have been so impressed with the hard work and dedication from this year’s cohort. Please encourage friends and colleagues to apply to be a leader or mentor. I encourage you to be an active member of CLD. We would like to invite you to become involved in your state or local chapter, or volunteer to serve on a committee. For more information please feel free to contact me via email (lambertma@appstate .edu). Also, consider joining us on Facebook or Twitter. Greetings! This spring the CLD Board of Trustees (BOT) will be reviewing our accomplishments and looking into areas where we need to grow. The Spring BOT meeting was held on March 23, 2012. Board members continued to address CLD’s priorities, including fiscal responsibility, membership, conferences and professional development, as well as ongoing committee goals. The June issue of LD Forum will include updates from our BOT meeting and highlights of committee work. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the BOT members for all of their work on behalf of CLD. There are a few updates concerning the BOT. Sarah Semon is moving from the position of secretary to chair of the Technology Committee. I would like to take this opportunity to thank her for all of her work as secretary. We are excited to have her as Technology chair, and I know she will be a great leader of that committee. Diane Bryant and Judy Voress are the Conference Committee co-chairs. We are very excited to have them in this capacity and assisting CLD. Chris Curran and Kathleen Hughes Pfannenstiel are co-chairs of the ad hoc Professional Committee. They have been quite busy since the fall conference working on webinars to support the mission of CLD. Under the guidance of President-Elect Caroline Kethley and Vice-President Silvana Watson, with the Conference Committee co-chairs Diane Bryant and Judy Voress, the 2012 conference plans are well underway. Mark your calendars to attend the 34th Annual International Conference on Learning Disabilities in Austin, Texas, on October 10th and 11th, 2012. Don’t miss this opportunity for collegiality, resources, research dissemination, and networking with your CLD friends. You will find additional information in the LD Forum and on CLD’s website. It is also time to be thinking about nominating advocates and outstanding teachers who have made an impact on the lives of individuals and children with learning disabilities for the Floyd G. Hudson Service Award and Outstanding Teacher Monica Lambert 2011–2012 CLD President In This Issue . . . President’s Message. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 34th International Conference on LD . . . . . . . 2 Awards Nominations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3 Call for Applications . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5 5 Ways to. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 CLD Board of Trustees . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 CLD Information Central . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 1 Learning Disabilities: Looking Back and Looking Forward— Using What We Know to Create a for the Future 34th International Conference on Learning Disabilities For many years, researchers and policy makers from various disci- October 10–11, 2012 Omni Austin Hotel Downtown Austin, Texas more. Although we have developed a solid foundation of knowledge, plines who are interested in learning disabilities (LD) have responded to questions about definition, identification, intervention, and much we continue to seek evidence to inform many areas in LD. For more than three decades, practitioners, researchers, parents, and advocates have gathered at the International Conference on Learning Disabilities to learn new information about LD and to network with colleagues. At this year’s 34th international conference, let’s look back with appreciation for developments in our field so that we may confidently look forward to create our blueprint for the future of LD. The 2012 Inter national Conference on Learning Disabilities will provide panel discussions, cracker-barrel sessions, and poster presentations focusing on topics related to understanding and studying LD, such as: • • • • • • • identification & classification assessment and intervention cultural & linguistic diversity teacher education research methodologies neuropsychological aspects of LD policy Make plans to join us in Austin next October! CLD WEBSITE: www.cldinternational.org COUNCIL FOR LEARNING DISABILITIES IMPORTANT: PLEASE READ CLD has booked a block of rooms at the Omni Austin Hotel Downtown as a courtesy to our valued attendees. We work hard to make sure that the conference rate is competitive, and we monitor the hotel’s other rates to make sure that our attendees are receiving the best deal. Your stay helps our organization meet our obligation to the hotel, allowing us to keep registration rates lower than many other conferences. Without your hotel stay, our organization may be assessed a financial penalty. This would jeopardize our ability to provide quality educational opportunities in the future. Please help us as we work to continue the many benefits of this conference. ***Several other events are taking place in Austin around the time of the CLD conference. For example, the Austin City Limits Music Festival will begin on Friday, October 12, 2012. Hotels will likely be SOLD OUT well before October 2012. CLD urges you to reserve your hotel room promptly at the Omni Austin Hotel Downtown to ensure availability.*** See the CLD website for conference registration and hotel booking information, which will include CLD’s hotel code for the conference sleeping room rate.This information will be posted in the very near future on our website. AWARDS NOMINATIONS 2012 Outstanding Teacher of the Year Award Each year, the Council for Learning Disabilities recognizes outstanding teachers who are CLD members and who consistently provide quality instruction to students with learning disabilities. These teachers, selected by local chapters, provide direct services to students. They are dedicated to implementing evidence-based instructional practices and collaborating with classroom teachers and other service providers to greatly improve the quality of education for all students who struggle academically. Provide direct services to students with learning disabilities Implement evidence-based instructional practices that result in significant gains in achievement for children, adolescents, or adults who struggle academically Advocate for persons with learning disabilities Contents of Nomination Packet Completed Nomination Form and vita (maximum 2 pages) Three (maximum) letters of recommendation (from supervisor, colleague, and/or other professionals) Two testimonials from parents or students Responses to “Statement of Educational Practices” (submitted in 12-point font and double spaced) Submit completed packet to local chapter president Awards Benefits Recipients are guests at the annual international conference and receive a complimentary registration. During the conference-award program, they receive a certificate of recognition and an honorarium. These CLD members are also profiled in LD Forum and are given a 1-year membership renewal. Criteria for Nomination Be a member of CLD or join as part of the application process Teacher of the Year Nomination Form Nominee: _________________________________________________________________________________ Address: __________________________________________________________________________________ City/State: _________________________________________________________ Zip: _________________ Phone: ______________________________ email: _____________________________________________ Current job title/Employer: ___________________________________________________________________ Chapter/Representative submitting nomination: ___________________________________________________ Representative contact information: ____________________________________________________________ Statement of Educational Practices Describe your current teaching responsibilities and explain how your instructional practices and collaborative efforts support district- and building-level goals for meeting the needs of all students within a Response to Intervention model. (500-word maximum) Deadline: Chapter submission deadline to be determined by individual chapters. Chapter presidents must submit nomination packets to the Leadership Development Committee chairperson by May 15, 2012. Candidates not affiliated with a local chapter may be nominated by a CLD member, who will submit the nomination packet to the LDC chairperson. Questions may be submitted to the chairperson (kyle.hughes@yahoo.com). Leadership Development Committee Chairperson: Kyle Hughes, 1011 S. Cove Way, Denver, CO 80209 3 AWARDS NOMINATIONS 2012 Floyd G. Hudson Service Award The Floyd G. Hudson Service Award is presented by the Council for Learning Disabilities for outstanding performance and commitment by a professional who works in the field of learning disabilities in a role outside of the classroom. This CLD member, working in a leadership capacity, enhances the professional learning of others in the field and has an impact on the lives of persons with LD. This award is named in memory of Dr. Floyd G. Hudson, a professor at the University of Kansas, who was a leader in the early years of CLD. Floyd was instrumental in formulating early policy to drive federal and state initiatives in the area of learning disabilities. Don Deshler has said of Floyd, “As I visit many schools across Kansas, Missouri, and Nebraska, I can really see Floyd’s lasting influence. He was a kind, generous, innovative, and collaborative professional. He worked closely with many school districts in solving problems, preparing teachers, and implementing more effective programs. Even today, many people here in the Midwest and around the country tell me about their positive experiences working with Floyd, many of which took place more than 20 years ago.” Award Benefits The recipient is a guest at the annual international conference and receives a complimentary registration and membership renewal. During the conference award program, he or she receives a certificate of recognition and an honorarium. The recipient will also be profiled in LD Forum. Criteria for Nomination Be a member of CLD or join as part of the application process Provide professional development/consulting services or serve in a leadership role working with teachers, other professionals, parents, and students Provide exemplary services to the field of learning disabilities for a minimum of 5 years Contents of Nomination Packet Completed nomination form and vitae (maximum of 2 pages) Three (maximum) letters of recommendation (from supervisor, colleague, and/or other professionals) Testimonials from parents or students, if applicable Responses to questions from Statement of Educational Practices (750 words) Floyd G. Hudson Outstanding Service Award Nomination Nominee: _________________________________________________________________________________ Address: __________________________________________________________________________________ City/State: _________________________________________________________ Zip: _________________ Phone: ______________________________ email: _____________________________________________ Current job title/Employer: ___________________________________________________________________ Chapter/Representative submitting nomination: ___________________________________________________ Contact information for representative: __________________________________________________________ Statement of Educational Practices Describe your role as a professional in the field of special education. How does this role allow you to impact instructional practices and provide support to students with learning disabilities? In addition, describe the most critical issues relevant to delivery of academic support for all students who struggle in school. How do you address these issues in your role as a professional? (750-word maximum) Deadline: Chapter submission deadline to be determined by individual chapters. Chapter presidents must submit nomination packets to the Leadership Development Committee chairperson by May 15, 2012. Questions may be submitted to the chairperson (kyle.hughes@yahoo.com). Leadership Development Committee Chairperson: Kyle Hughes, 1011 S. Cove Way, Denver, CO 80209 The Leadership Development and Executive Committees of CLD are responsible for the selection of the award recipient. AWARDS NOMINATIONS 2012 Outstanding Researcher Award The paper should conform to the style of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, and be no more than 35 double-spaced pages in length (including references, tables, figures, and appendices). Submit papers by email to: Linda Nease, CLD Executive Director Lneasecld@aol.com To promote and recognize research, the Council for Learning Disabilities annually presents an award for an outstanding manuscript-length paper on learning disabilities based on a doctoral dissertation that has been completed within the last 5 years. The winner will receive a plaque to be presented at the Awards Ceremony on Wednesday, October 12th, 2012, during the 34th International Conference on Learning Disabilities in Austin, Texas. In addition, the paper will be considered for publication in Learning Disability Quarterly. Deadline for Paper Receipt: May 1st, 2012 The winner will be notified by August 15th, 2011. Call for Applications: CLD Leadership Academy CLD is committed to building the leadership capacity of pro- service Teacher, Outstanding Doctoral Candidate and Outstand- fessionals who are entering the special education field. Addi- ing Researcher. tionally, this support is extended to those who have been in the Each year, CLD selects a cadre of up to 6 emerging lead- field and who now want to move into professional leadership ers who demonstrate potential and a passion for leadership in roles. Participation in the Leadership Academy provides the service of students with learning disabilities as well as all other opportunity to assume a leadership role on a local, state, and learners who struggle academically. Send nomination materi- national level in service to students with learning disabilities als on or before June 1, 2012, to Kyle Hughes, CLD Lead- and their families. Academy Leaders have the opportunity to ership Development Committee Chair (kyle.hughes24.gmail network and receive mentoring from some of the most highly .com). Winners will be notified by August 1, 2012. Additional regarded leaders in the field of learning disabilities. Addition- information and application materials are available at: ally, Academy Leaders are eligible for nomination for CLD http://www.cldinternational.org/About/Leadership_ annual awards, including Outstanding Teacher, Outstanding Pre- Academy.asp. Follow CLD on Twitter http://twitter.com/CLDIntl and “Like” the CLD Facebook Page https://www.facebook.com/pages/Council-for-Learning-DisabilitiesInternational/196204000418174 5 Editor’s Note: This column provides readers with immediate access to evidence-based strategies on current topics that can easily be transferred from the pages of LD Forum into effective teaching practice in CLD members’ classrooms. Authors who would like to submit a column are encouraged to contact the editor in advance to discuss ideas. Author guidelines are available on CLD’s website and from the editor, Cathy Newman Thomas (thomascat@missouri.edu). 5 Ways To . . . Increase Student Participation in the Secondary Classroom Brittany Hott and Jennifer Walker George Mason University Embrace Technology. Today’s secondary students are major consumers of media. With widespread access to the Internet and increasing options for incorporating technology in the classroom, teachers can tap into a plethora of free or low-cost options to enhance instruction and support student learning. Technology provides an outlet to foster active participation, ensuring that each student has the opportunity to participate. Some options include the use of (a) response tools, (b) virtual learning environments, and (c) social media outlets. See Table 1 for a list of websites and online instructional media. A. Response tools. By incorporating a variety of response tools, teachers offer more students the opportunity to respond to teacher questions or problems, increasing the likelihood that they will master critical concepts. Response tools can be low, medium, or high technology applications that allow each student to respond to problems posed by the instructor. Low technology options include the use of preprinted response cards and Post-it® notes. Heward et al. (1996) defined response cards as items that students can use to respond to a teacher question or problem. For each student, the teacher uses card stock or index cards to create a set of cards that include the answers true and false or the letters A, B, C, D. Depending on student needs, a teacher can orally ask questions or incorporate them in a PowerPoint presentation and read aloud. Following a teacher question, students select an answer from the set of cards. Another option is to use paint sticks from a local hardware store, labeled with the words true on one side and false on the other: Students can flip the paint stick to the true or false side to indicate their response. When eliciting a short-answer response from students, the teacher can use a variety of response tools, such as Post-it ® notes. Each student is provided with a small stack of notes upon which he or she can write a quick answer to each question posed by the instructor. In addition, individual student white boards can be easily created by cutting a piece of shower board from a local hardware supply company and taping the sharp edges with duct tape. Students can then respond to a multitude of questions using a dry erase marker (George, 2010). The teacher can view each student’s response from the front of the classroom or by walking by students’ desks. High levels of student engagement have been positively associated with academic and social gains in adolescents. Moreover, interventions linked to high levels of active student participation demonstrate increased achievement, improved time on-task, and positive peer interactions (Randolph, 2007). While the literature indicates the need to increase opportunities for students to be directly engaged and respond during instruction (Vaughn & Bos, 2011), as students advance in their studies, teachers increasingly rely on a whole-group lecture format that significantly hinders student participation and active learning. This lecture format proves to be particularly challenging for many students with learning disabilities (LD; Vaughn, Hughes, Moody, & Elbaum, 2001). Rather than relying on students to be prepared with the knowledge, skills, and confidence to benefit from academic instruction, teachers, particularly at the secondary level, must be equipped to support active student participation (Berry, 2006). Given the link between high levels of participation and academic progress, educators must provide multiple means for all students to actively participate in class. These five tips can be used to foster student participation in secondary classrooms. 2 Carefully Plan Lessons. It is important to thoughtfully plan lessons to ensure systematic progression through the modeling, guided practice, and independent practice phases (Fisher & Frey, 2010). Students with LD benefit from direct and systematic instruction (Jitendra, Edwards, Sacks, & Jacobson, 2004), which requires teachers to place greater emphasis on the modeling and guided practice portions of the lesson. Furthermore, research has indicated a positive correlation between high levels of correct responding throughout the lesson phases and increased achievement (Sutherland, Alder, & Gunter, 2003). Therefore, teachers must closely monitor progress to ensure that students practice completing problems accurately. To support secondary students, Gunter, Coutinho, and Cade (2002) suggested that for each minute of instruction, the guided practice portion of a lesson should incorporate 4 to 6 opportunities for each student to respond. Further, students should respond with 80% accuracy. During independent practice activities, where the goal is to promote autonomy, each student should have 9 to 12 opportunities to respond and should respond with 90% to 95% accuracy (Scheuermann & Hall, 2008). Building these opportunities into lessons is a critical step that will facilitate the opportunity for all students to actively participate in class. 1 (continued on page 7) 6 (Five Ways To, continued from page 6) Table 1. Technology Applications for Increasing Participation Application Resources Description Response systems www.irespond.com www.turningtechnologies.com www.replysystems.com Websites include information about software, response systems, and purchasing details. Response tool: Avatars www.voki.com www.goanimate.com Websites share detailed directions for classroom use. Students create characters to present information. Virtual learning environments www.explorelearning.com http://phet.colorado.edu/en/ simulations/category/new Online simulations of math and science concepts http://www.khanacademy.org/ http://virtualnerd.com/ Online discussion www.blogspot.com www.facebook.com www.twitter.com www.wikispaces.com Social media to elicit student responses and discussions via the Web; see the following YouTube demonstrations for how to use each social media option: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-dnL00TdmLY http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rA4s3wN_vK8 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ddO9idmax0o http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUnmowztKMQ websites that include a simulated learning environment, an interactive online scenario that allows students to explore the effects of various experimental conditions (Lunce, 2006). These sites allow students with LD to access advanced science and mathematics concepts (Simpson, 2009). Students can explore difficult concepts such as chemical reactions or the Pythagorean theorem without expensive lab equipment or manipulatives (e.g., biology concepts such as survival of the fittest). Students can choose various colorings of animals to discover outcomes for species in various environments. Many of these websites provide immediate feedback, thus decreasing the likelihood that students practice errors. C. Social media outlets. Recent research endeavors have indicated that social media outlets, such as Twitter and Facebook, can be utilized as means of facilitating responses from students (e.g., Allsopp, McHatton, & Farmer, 2010). Blogs, wikis, and teacher websites offer opportunities for information dissemination and serve as prompts for classroom discussions. For example, the teacher might post a political cartoon to a wiki, class blog, or Facebook page; students would then post their interpretations and provide feedback to their classmates’ opinions. The teacher can add comments, pose questions, or serve as a moderator. Whatever the selected technology from the numerous options to enhance instruction may be, make the decision to use it based on parsimonious conditions. Selection should be based on the qualities of instructional effectiveness, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness (King-Sears & Evmenova, 2007). Online response tools allow students to input phrases or simple sentences to problems and questions (McClannon & Kortering, 2010). An example is an avatar, which is a virtual character. In these online systems, teachers can pose the same question to the entire class or scaffold questions to meet individual student needs. Students then create avatars by logging onto a free site and entering text that the avatars will then read aloud. The avatars can be used in isolation or to create a dialogue among two or more characters. This allows each student to respond to a question and avoids the need to speak in front of the class. Students have opportunities to edit their writing after hearing the avatars read their response aloud exactly as it is typed. Avatars can be used across subject areas. For example, students could create a debate between a Republican and Democrat running for an office, with each avatar representing a character. The students can type the dialog that would occur between characters and then share their skit with the instructor or class. High technology electronic devices, such as clickers (Blood, 2010), can be used to quickly poll an entire class. These devices are appropriate for forced-answer choices, such as true/false or multiple choice question types, and for short-answer questions. Each student is provided with a handheld device similar to a small cell phone. As a teacher poses a question or problem, students choose an answer, which appears on a screen. The teacher then displays the correct answer on the screen. Teachers can also share class averages so students can see how well they did in comparison to peers. Clickers can be used for content, to elicit student opinions, as an assessment to see if students have read the material, and to monitor comprehension during lecture and discussion. Advantages of clickers include immediate feedback for students and data for teachers. B. Virtual learning environments. In addition to response tools, teachers can incorporate into their instruction a variety of free 3 Develop Self-Efficacy Through Choice and Differentiation. Self-efficacy, which encompasses beliefs about (continued on page 8) 7 (Five Ways To, continued from page 7) through a lesson, allow students the wait time to consider responses while providing encouragement to support self-efficacy. Correct responses or increased effort in engagement should be rewarded with genuine, specific praise. Feedback should not only encourage further responses but also provide students with information about their level of understanding (Burnett, 2003). When students provide partially correct answers, acknowledge the correct part and attempt to elicit additional information. If students respond with incorrect answers, tactfully acknowledge that the answer was incorrect and either provide the correct answer or prompt the student for additional information. Regardless of the answer, praise should be used as a frequent motivator to elicit responses from students and contribute to their self-efficacy. Such praise may be especially important to students with LD, who need encouragement to persist. one’s ability to be successful in specific domains and when completing situational tasks (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007), can be challenging for adolescents, particularly individuals with disabilities. Specifically, students with LD have reported lower academic selfefficacy than their nondisabled peers (Lackaye, Margalit, Ziv, & Ziman, 2006). Students with low self-efficacy may view their own deficits in performance as an indication of their lack of intelligence (Ramdass & Zimmerman, 2008). Students’ beliefs about their capabilities affect their investment in, and persistence regarding, schoolwork (Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2003). For some adolescents with LD, poor performance on academic tasks may be less about skills and more about the ability to manage their own learning (Klassen, 2010). Because self-efficacy, motivation, engagement, and effort are often related (Lackaye & Margalit, 2008), teachers should focus on motivating and engaging students to the greatest extent possible. Allow students to have a voice when demonstrating mastery of content material. Build student confidence by offering them opportunities to manage their learning (Klassen, 2010). Offering choices and options when completing tasks can ensure student success in a non-threatening manner. Thoughtfully and deliberately plan how to engage students in ways that tap into strengths and experiences. Such opportunities will not only increase student self-efficacy but also ultimately their desire to participate and engage in the classroom by giving them a sense of ownership of, and success with, the material. To boost self-efficacy, teachers can use differentiated questioning throughout lessons to fully engage students at every academic level within the classroom (Friend & Bursuck, 2008). Pose questions at a variety of levels and call on students who can respond accurately, boosting student confidence and self-efficacy with course material. To encourage all students to respond, consider asking students to restate or repeat previously taught information. To further stimulate class discussion, probe for clarification and analysis of responses. Another option is to coach adolescents with leading questions that encourage them to think about answers by defining vocabulary from the topic area (Sullivan, Mastropieri, & Scruggs, 1995). Prompts may include inquiries that ask students to share everything they know about a topic as a way to get students to approximate answers to questions. At the same time, be sure to call on students who volunteer responses to promote engagement. Discussions should have both flexibility and structure while maintaining focus and clarity with the topic area. Some students with LD may also benefit from opportunities to activate prior knowledge with an anticipation guide, which includes statements related to the material students are to discuss during a lesson (Burns, Roe, & Ross, 2001). A guide can pique students’ interest in the subject, creating a purpose for attending to lessons and responding to questions. Finally, to elicit responses while moving Facilitate Cooperative Learning Groups. Cooperative learning, an evidence-based instructional practice, is a great alternative to whole-group lecture. Social learning opportunities are highly motivating for adolescents. Cooperative learning assigns students to small groups for collaboration to complete group activities. Create cooperative groups to include students of mixed abilities who have a common goal. To engage students, carefully plan, monitor, and assess groups as they progress toward goals. Student individuality—as well as positive interdependence—should be carefully balanced to promote student accountability and group goal setting (Gillies, 2007). During the planning stages, purposefully and explicitly teach students procedures for cooperative grouping to achieve success. Assign each student a responsibility within the cooperative group, such as recorder, reader, accuracy coach, summarizer, or leader. The key to selecting content for cooperative learning is to include curricular material that has already been introduced to students but requires additional knowledge and practice to meet objectives, rather than requiring initial mastery through groupings (Friend & Bursuck, 2008). There are many ways to effectively use cooperative learning groups. Four Corners, Slash the Trash, and Agreement Circles are viable options. Four Corners is particularly useful when discussing controversial topics. An option or opinion is placed in each corner of the classroom. Students view each choice and then stand next to the choice that they think is the most plausible. After selecting the choice, students meet with their group and discuss advantages and disadvantages of their choice. A class discussion can follow the activity. To play Slash the Trash, the instructor poses several assumptions, and students then debate which assumption should be trashed. For example, several options for dealing with health care could be posed. Students then discuss which options should be 4 (continued on page 9) 8 (Five Ways To, continued from page 8) Implement Self-Monitoring Procedures. Selfmonitoring, an effective strategy that can increase student participation and/or assist teachers and students with monitoring responses, is a tool that shifts the responsibility from the teacher to the student (King-Sears, 2008). Students develop increased independence and learn strategies that will serve them as they progress through their school career. With guidance, students can be taught to self-monitor academic and behavioral performance (e.g., they can learn to monitor their own level of attention, which may include on-task behaviors or engagement with lesson material). Teaching students to self-monitor is an on-going process that requires frequent feedback, evaluation from teachers, and possibly reevaluation of goals and progress. Teachers should work collaboratively with students who under- or overrespond to set goals for a predetermined period of time or for a class block. Goals can focus on the number of questions or problems that will be solved, the number of times students will raise their hand to participate, or the percentage of time students hope to demonstrate active attention during lectures. After reasonable and attainable goals have been mutually agreed on by the student and teacher, the next step is for the student to learn to track progress. A monitoring card, basic spreadsheet, or Google document used across settings (Blood, 2011) can be utilized. Other resources, such as commitment cards and self-monitoring cards, can be found at iKidTools (http:// kidtools.org) and customized for individual students, including adolescents. Whatever the method, the self-monitoring process should be easily used by both the student and teacher. As monitoring progresses, the teacher and student should discuss progress and adjust goals as needed (King-Sears, 2008). Frequent checks of monitoring must occur early in the process so that a student can learn how 5 considered and which options should be eliminated or trashed. An Agreement Circle is created by having each student stand in a circle around the teacher or selected student. A statement is made. Students who agree with the statement step into the circle. The class then discusses reasons for agreement or disagreement. Additional options for cooperative grouping include the Three-Step Interview, Reading Groups, Three Stay One Stray, Round Robin Brainstorming, and Think Aloud Pair Problem Solving, as outlined in Table 2. Group work should include careful monitoring of student interactions by the teacher, and determinations should be made about students’ ability to cooperate (Friend & Bursuck, 2008). Monitor the capability of particular groups of students to interact positively and contribute equally to cooperative learning. It may be necessary to assist groups or individual students with specific tasks or to demonstrate activities for some groups. If groups struggle with interacting positively or cannot work cohesively, they can be reconfigured prior to planning subsequent cooperative learning activities. Several evaluation considerations regarding cooperative learning groups need to be addressed. Evaluate on individual and group levels, carefully paying attention to both individual contributions and final products. In addition, evaluate the interactions among groups as they relate to sharing, encouraging, supporting, and respecting. Give students a voice in the assessment process by soliciting feedback (e.g., self-monitoring, self-assessment) about the final product and the cooperative learning process (Mastropieri & Scruggs, 2010). Consider each component as well as the whole process when factoring the final evaluation. Table 2. Ideas for Cooperative Learning Groups Group Type Description Three-Step Interview Four-member teams group in two sets of partners. Members interview their partners about material covered in class, asking clarifying questions. During the second step, partners reverse roles and the interviewer becomes the interviewee. Finally, members share the information they gleaned from their partners with the entire team (Bromley & Modlo, 1997). Reading Groups In small groups, students create reading groups with assigned roles. Members serve as the reader, recorder, checker (Johnson, Johnson, & Holubec, 1991), connector (connecting the information to everyday situations), questioner (analyzing text), or illustrator (Anderson & Corbett, 2008). Students rotate through these roles while reading and answering corresponding questions. Three Stay, One Stray During group work, one member from each group shifts to another group to explain their progress and gather information from the other group. Members gain alternative views and perspectives through this sharing progress. Once members have returned to their original groups, this process may be repeated with other “strayers” (Vidakovic & Martin, 2004). Round Robin Brainstorming Groups of four to six are asked a question with multiple answers. A group recorder is appointed, and after a predetermined amount of time to think, members of the team share responses in a round robin manner. Members continue to provide answers in an orderly fashion until time is called (Bromley & Modlo, 1997). Think Aloud Pair Problem-Solving In groups of four, students work to solve a problem. Two of the members of the group are designated as problemsolvers and two are listeners. While working on a solution, the problem-solvers verbalize their thinking while the listeners may offer encouragement or offer suggestions if the problem-solvers ask for assistance. Roles may be reversed for the next problem (Sormunen, 2008). (continued on page 10) 9 (Five Ways To, continued from page 9) to accurately and correctly monitor goals. Teachers should expect some errors when first initiating a self-monitoring system, as selfreporting may be difficult. For students to better understand their progress in such systems, having them graph progress may also prove beneficial because it offers a visual record of their performance. Such a visual representation of progress may contribute to student motivation. Goals should be periodically monitored, adjusted, and incrementally increased as a way to increase student participation. After the student reaches, maintains, and sustains a desired participation rate, the self-monitoring device can be phased out. See Figure 1 for an example of a self-monitoring chart. Conclusion A variety of student-, peer-, and teacher-directed strategies can be used to increase student participation. Students with LD often exhibit insufficient participation rates and need support to successfully navigate whole-group instruction (Hamilton, Fuchs, Fuchs, & Roberts, 2000). The aforementioned tips do not begin to address all of the options that may be implemented. However, each provides a means to increase student participation and ultimately support increases in academic achievement. References Allsopp, D. H., McHatton, P. A., & Farmer, J. L. (2010). Technology, mathematics, PS/RTI, and students with LD: What do we know, what have we tried, and what can we do to improve outcomes now and in the future? Learning Disability Quarterly, 33, 273–288. Anderson, P. L., & Corbett, L. (2008). Literature circles for students with learning disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 44, 25–33. Berry, R. A. W. (2006). Teacher talk during whole-class lessons: Engagement strategies to support the verbal participation of students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 21, 211–232. Blood, E. (2010). Effects of student response systems on participation and learning of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 35, 214–228. Blood, E. (2011). Point systems made simple with Google docs. Intervention in School and Clinic, 46, 305–309. Bromley, K., & Modlo, M. (1997). Using cooperative learning to improve reading and writing in language arts. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 13, 21–35. Burnett, P. C. (2003). The impact of teacher feedback on student self-talk and self-concept in reading and mathematics. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 38, 11–16. Burns, P. C., Roe, B. D., & Ross, E. P. (2001). Teaching reading in today’s elementary schools (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. Fisher, D., & Frey, N. (2010). Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for gradual release of instructional responsibility. Arlington, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Friend, M., & Bursuck, W. D. (2008). Including students with special needs: A practical guide for classroom teachers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. George, C. L. (2010). Effects of response cards on the performance and participation of middle school students with emotional or behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 35, 200–213. Gillies, R. M. (2007). Cooperative learning: Integrating theory and practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Gunter, P., Coutinho, M., & Cade, T. (2002). Classroom linked to academic gains among students with emotional and behavioral problems. Preventing School Failure, 46, 126–132. Hamilton, C., Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Roberts, H. (2000). Rates of classroom participation and the validity of sociometry. School Psychology Review, 29, 251–266. Heward, W. L., Gardner, R., III, Cavanaugh, R. A., Courson, F. H., Grossi, T. A., & Barbetta, P. M. (1996). Everyone participates in this class: Using response cards to increase active student response. Teaching Exceptional Children, 28, 4–11. Figure 1. Example of Self-Monitoring Chart Student: _______________________________ Class: ___________________________ Date: _________________________________ Topic: ___________________________ Directions: Next to each question, respond with “yes,” “no,” or “partially” to indicate your task completion. Use the cues below each question to help you make your decision. Did I bring my materials? Textbook: Paper: Pencil: Do I know what assignments are due in the next 2 weeks? Homework: Projects: Did I participate in class? Asked questions Answered questions Submitted classwork assignments Am I getting prepared for the next class? Recorded homework assignment in agenda planned for upcoming projects, quizzes, tests Notes: Total Yes: Total No: Total Partial: 10 (continued on page 11) (Five Ways To, continued from page 10) Jitendra, A. K., Edwards, L. L., Sacks, G., & Jacobson, L. A. (2004). What research says about vocabulary instruction for students with learning disabilities. Exceptional Children, 70, 299–323. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Holubec, E. J. (1991). Cooperation in the classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book. King-Sears, M. E. (2008). Using teacher and researcher data to evaluate the effects of self-management in an inclusive classroom. Preventing School Failure, 52, 25–34. King-Sears, M. E., & Evmenova, A. S. (2007). Premises, principles, and processes for integrating technology into instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children, 40, 6–14. Klassen, R. (2010). Confidence to manage learning: The self-efficacy for self-regulated learning of early adolescents with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 33, 19–30. Lackaye, T., & Margalit, M. (2008). Self-efficacy, loneliness, effort, and hope: Development differences in the experiences of students with learning disabilities and their non-learning disabled peers at two age groups. Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, 6, 1–20. Lackaye, T., Margalit, M., Ziv, O., & Ziman, T. (2006). Comparisons of self-efficacy, mood, effort, and hope between students with learning disabilities and their non-LD-matched peers. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 21, 111–121. Linnenbrink, E. A., & Pintrich, P. R. (2003). The role of self-efficacy beliefs in student engagement and learning in the classroom. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19, 119–137. Lunce, L. M. (2006). Simulations: Bringing the benefits of situated learning to the traditional classroom. Journal of Applied Educational Technology, 3, 37–45. Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (2010). The inclusive classroom: Strategies for effective differentiated instruction. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. McClannon, T., & Kortering, L. (2010). Universal design for learning: Bring it into your classroom. Paper presented at the 32nd Annual In- ternational Conference for Learning Disabilities, Myrtle Beach, SC. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/udlaccess/my-forms Ramdass, D., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Effects of self-correction strategy training on middle school students’ self-efficacy, self-evaluation, and mathematics division learning. Journal of Advanced Academics, 20, 18–41. Randolph, J. J. (2007). Meta-analysis on the research on response cards: Effects on test achievement, quiz achievement, participation, and offtask behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9, 113–128. Scheuermann, B. K., & Hall, J. A. (2008). Positive behavioral supports for the classroom. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s selfefficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 23, 7–25. Simpson, E. S. (2009). Video games as learning environments for student with learning disabilities. Children, Youth, and Environments, 19, 306–319. Sormunen, K. (2008). Fifth graders’ problem solving abilities in openended inquiry. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 3, 48–55. Sullivan, G. S., Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (1995). Reasoning and remembering: Coaching thinking with students with learning disabilities. The Journal of Special Education, 29, 310–322. Sutherland, K. S., Alder, N., & Gunter, P. L. (2003). The effect of varying opportunities to respond to academic requests on the classroom behavior of students with EBD. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 11, 239–249. Vaughn, S. R., & Bos, C. S. (2011). Strategies for teaching students with learning and behavior problems (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. Vaughn, S., Hughes, M. T., Moody, S. W., & Elbaum, B. (2001). Instructional grouping for reading for students with LD: Implications for practice. Intervention in School and Clinic, 36, 131–138. Vidakovic, D., & Martin, W. O. (2004). Small-group searches for mathematical proofs and individual. 2011–2012 CLD Board of Trustees Executive Committee President Monica A. Lambert Appalachian State University lambertma@appstate.edu President-Elect Caroline Kethley Southern Methodist University ckethley@mail.smu.edu Vice President Silvana Watson Old Dominion University swatson@odu.edu Past President Carolina Dunn Auburn University dunncal@auburn.edu Treasurer Steve Chamberlain The University of Texas at Brownsville & Texas Southmost College steve.chamberlain@utb.edu Secretary: Open Parliamentarian Tandra Tyler-Wood University of North Texas Tandra.Wood@unt.edu Executive Director Linda Nease lneasecld@aol.com Standing Committee Chairs Communications Judy Voress The Hammill Institute on Disabilities jvoress@hammill-institute.org Conference Planning Brian R. Bryant The University of Texas at Austin brianrbryant@aol.com Diversity Jugnu P. Agrawal George Mason University & Fairfax County Schools JPAgrawal@fcps.edu Finance Steve Chamberlain The University of Texas at Brownsville & Texas Southmost College steve.chamberlain@utb.edu Standards and Ethics Open position Technology Sarah Semon University of Northern Iowa sarah.semon@uni.edu Leadership Development Kyle Hughes kyle.hughes@yahoo.com CLD Editors Liaison Roberta Strosnider Towson University rstrosnider@towson.edu LDQ Co-Editors Diane P. Bryant Brian R. Bryant dpbryant@mail.utexas.edu brianrbryant@aol.com Debi Gartland Towson University dgartland@towson.edu Membership/Recruitment Robin H. Lock Texas Tech University robin.lock@ttu.edu Research Patricia Mathes Southern Methodist University pmathes@smu.edu LDQ Associate Editor Kirsten McBride kmcbr41457@aol.com LD Forum Editor Cathy Newman Thomas The University of Missouri thomascat@missouri.edu Website Editor Richard A. Evans richard.evans@angelo.edu CLD Information Central CLD Mission, Vision, & Goals Mission Statement: The Council for Learning Disabilities (CLD) is an international organization that promotes evidencebased teaching, collaboration, research, leadership, and advocacy. CLD is composed of professionals who represent diverse disciplines and are committed to enhancing the education and quality of life for individuals with learning disabilities and others who experience challenges in learning. Vision Statement: Our vision is to include all educators, researchers, administrators, and support personnel to improve the education and quality of life for individuals with learning disabilities and others who experience challenges in learning. Convenient E-Access to ISC and LDQ • You can access your complimentary members-only subscription to Intervention in School and Clinic through the CLD website. Articles are searchable by keyword, author, or title and are indexed back to 1998. Simply log-in through our Members’ Only portal(https://www.cldinternational.org/Login/ Login.asp) and then click on the link provided. • Learning Disability Quarterly online access for CLD members will be available later this year. Infosheets Infosheets provide concise, current information about topics of interest to those in the field of learning disabilities. Current Infosheets are available for viewing and download at https://www.cldinternational.org/Infosheets/Infosheets.asp External Goals 1. Promote the use and monitoring of evidence-based interventions for individuals with learning disabilities (LD) and others who experience challenges in learning. 2. Foster collaborative networks with and among professionals who serve individuals with LD and others who experience challenges in learning. 3. Expand our audience to educators, researchers, administrators, and support personnel. 4. Promote high-quality research of importance to individuals with LD and persons who experience challenges in learning. 5. Support leadership development among professionals who serve individuals with LD and others who experience challenges in learning. 6. Advocate for an educational system that respects, supports, and values individual differences. Contact Information Council for Learning Disabilities 11184 Antioch Road, Box 405 Overland Park, KS 66210 phone: 913-491-1011 • fax: 913-491-1012 Executive Director: Linda Nease CLD Publications Invite Authors to Submit Manuscripts Learning Disability Quarterly The flagship publication of CLD, LDQ is a nationally ranked journal. Author guidelines may be accessed at: Internal Goals http://www.cldinternational.org/Publications/LDQAuthors.asp 1. Ensure efficient, accountable, responsive governance to achieve the CLD mission. 2. Mentor future CLD leaders. 3. Maintain sound fiscal planning and practice. 4. Recruit and retain CLD members. 5. Increase the diversity of our organization. Intervention in School and Clinic ISC, a nationally ranked journal with a historical affiliation to CLD, posts author guidelines at: http://www.cldinternational.org/Publications/ISC.asp LD Forum The official newsletter of CLD, LD Forum accepts manuscripts for its Research to Practice and 5 Ways to… columns. Author guidelines are available at: http://www.cldinternational.org/Articles/RTP-5.pdf CLD on the Web Infosheets Research summaries on current, important topics, Infosheets are aligned with CLD’s tradition of translating research into practice to make it accessible and useful to practitioners. Author guidelines may be accessed at: www.cldinternational.org Visit the CLD website for all the latest updates! Read CLD’s Annual Report, position papers, conference news, Infosheets, and much more. https://www.cldinternational.org/Infosheets/Infosheets.asp 12