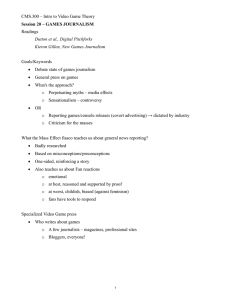

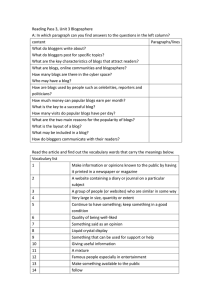

The Right to Blog

advertisement