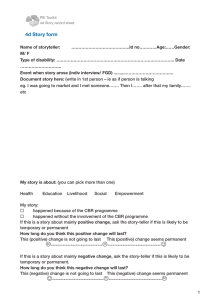

Special needs education and community-based programmes

advertisement