Smarter Not Harder - Ministry for Primary Industries

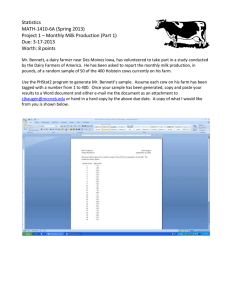

advertisement