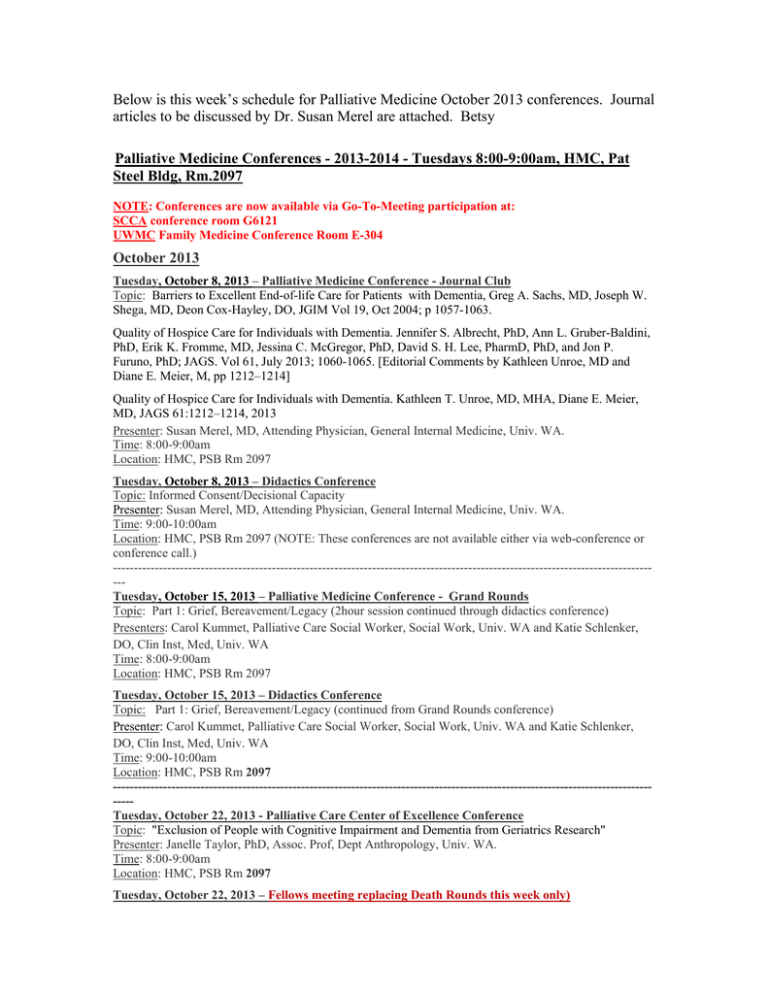

Below is this week`s schedule for Palliative Medicine October 2013

advertisement