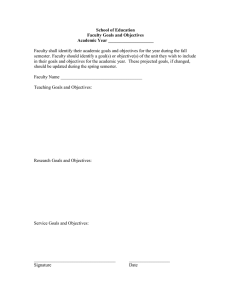

courses of instruction

advertisement