The Industry Training Authority and Trades Training in BC

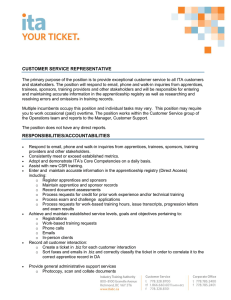

advertisement