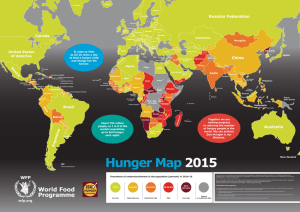

the high food price challenge

advertisement