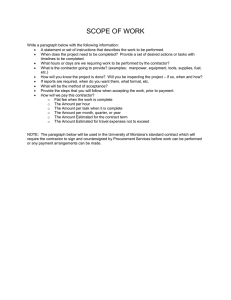

Construction Contract Clause Digest - Harmonie

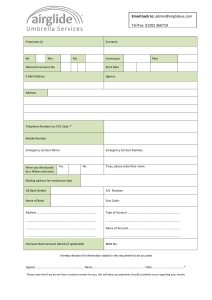

advertisement