Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association`s Resource Plan

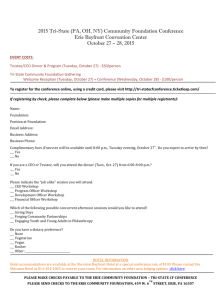

advertisement