Views about Physics held by Physics Teachers with Differing

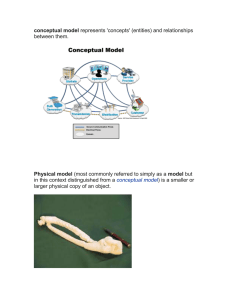

advertisement