Scientific evidence : new leads - Australian Institute of Criminology

advertisement

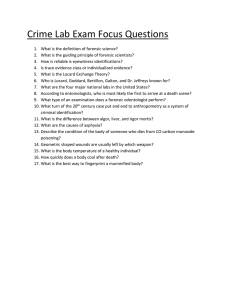

SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE - NEW LEADS Alastair M. Ross Director National Institute of Forensic Science INTRODUCTION In a paper entitled ‘Scientific Evidence - New Leads’, one would expect to learn about scientific break throughs and the latest technological developments. In this paper I intend to take poetic licence with the title. While there will be some discussion on scientific development, the paper will also raise issues relating to the quality of scientific evidence and the presentation of scientific evidence to the courts. In this, I will unashamedly be touching on the role of the National Institute of Forensic Science in these areas. BACKGROUND Whenever the topic of science is raised, the discussion centres around technological advances. For science to progress, this is natural and should be encouraged. However, progress must not be permitted to run too far ahead of proper validation and community acceptance. This is true for all science and particularly for forensic science. It is in forensic science where ultimately, the court will rule on its acceptance and the public, in the form of the jury, will make a judgement as to its relevance and significance in a given case. To a large degree then, the success of new leads in scientific evidence is not determined in the laboratory, but in the courtroom. It is therefore incumbent on forensic science to build into new technology the quality and validation required for acceptance and to properly inform the legal and general community of its strengths and limitations. DISCUSSION The discussion will centre around three main points: Building in Quality; Taking it to the Streets; Scientific Advances. Building in Quality Like it or not, industry regulation is upon us. The forensic science community, initially through the Senior Managers of Australian and New Zealand Forensic Laboratories (SMANZFL) and subsequently through SMANZFL and NIFS has, on its own initiative, developed a national laboratory accreditation program. The program is jointly managed by the National Association of Testing Authorities (NATA) and the American Association of Crime Laboratory Director’s Laboratory Accreditation Board (ASCLD/LAB). It is a comprehensive peer review of all aspects of forensic laboratory practice conducted by assessors, national and international, who are external to the laboratory. The assessment is underpinned by mandatory, regular external proficiency testing, the results of which are reviewed by an international panel. Sanctions are applied to accredited laboratories who, through assessment and proficiency tests, are found not to be meeting the comprehensive accreditation criteria. Three Australian laboratories are already accredited and the aim of SMANZFL is for all Australian laboratories to be accredited by the year 2000. A ‘new lead’ in the accreditation program is the inclusion of crime scene investigation. This discipline is not included in any other accreditation program, which is surprising given its fundamental importance in any forensic analysis. NIFS has sponsored a team of crime scene examiners representing all jurisdictions to develop discipline specific accreditation criteria and proficiency testing protocols. The group has been most innovative in its approach. Every examiner must undergo an internal proficiency test each year. This comprises assessment by a supervisor at an actual scene through the use of a set of national standards developed into a check list. The checklist is used to determine whether or not the examiner has adequately processed the scene. Any deficiencies result in counselling and retraining. In addition, each facility must undertake an external proficiency test each year. The external test is being developed using interactive CD Rom technology. This enables the person being assessed to ‘walk through’ a crime scene on a computer screen. The program gives the ability to zoom in on specific objects, take photographs and collect the object. Note books on the screen enable the assessee to record their observations, why they do or do not collect certain items and their probable significance to the case and how the objects are packaged and labelled. For the assessor, there is a complete audit trail including, for example, the total time spent on the test, the time spent in each section of the scene, items ‘zoomed’ and not collected and the notes made by the assessee. The test results will be considered by an external panel against model answers developed by the test designers. Sanctions will be applied to accredited facilities not meeting the criteria. The pilot program was demonstrated with sensational success at a recent meeting of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences meeting in Nashville. The concept has exciting implications for other disciplines and in the area of training. It will be an important component of building in quality. Taking it to the Streets The general public has an extremely keen interest in forensic science, beginning with students at secondary and even primary school level. Too often unrealistic expectations of forensic science are created through ill researched but popular film and television. It is the general public who constitute our juries and therefore, it is vital that they have access to a balanced view of the strengths and limitations of forensic science. 2 Similarly for legal counsel to effectively lead scientific evidence or test the evidence through cross examination, they must have a knowledge of at least the basic principles of the science being presented. Furthermore, the Judge or Magistrate must also have that knowledge to be able to assess the evidence. It is not appropriate, as is often the case, for the lack of scientific knowledge to be seen as a ‘badge of honour’ by members of the legal profession involved in trials where scientific evidence is presented. There are a number of ‘new leads’ being developed by NIFS to address the issue of information/knowledge transfer. Three of these are: multi-level information packages; national jury survey; forensic hypotheticals. Multi-level information packages In conjunction with the Victoria Forensic Science Centre, NIFS is developing a prototype of these packages with the topic being DNA profiling. The packages will be video/paper based and provide information at three different levels. The first level will provide basic principles type information for juries. The second level will be more complex and is aimed at legal counsel and the judiciary and the third and most complex level will provide information/training for scientists. One of the aims of the packages is to provide information which is based on national standards and therefore, endorsed by all States/Territories. Depending on the acceptance of this prototype which is due for completion in September of this year, packages involving other disciplines will be produced. National Jury Survey As a direct result of the National Forensic Summit held in Canberra in May last year, NIFS, the Australian Institute of Judicial Administration (AIJA) and the Australian Institute of Criminology(AIC) are combining forces to conduct a survey of past jurors. Two questions raised in a paper presented at the Summit by, Dr. James Robertson (General Manager, Forensic Science Services, Australian Federal Police) were: are the perceptions that jurors do not understand scientific or technical evidence valid? are jurors given sufficient access to information such as scientific reports? These questions have lead to the key aims of the survey which are: to determine the level of understanding of scientific/technical evidence by jurors and how this may be improved; to identify the needs of jurors regarding access to scientific/technical information during the trial process; to identify any improvements that can be made in the way in which scientific/technical evidence is presented to the courts. The aims of the survey sit well with current Federal Government policy viz: 3 ‘to develop an Australia-wide jury education program in consultation with and cooperation of State and Territory Governments. This program may well involve the development of ‘jury kits’ comprising an explanatory video and supplementary written materials for jurors’. Representatives of the legal and scientific communities will be involved in identifying appropriate cases and, therefore, juries to survey and in the development of the survey instrument. Forensic Hypotheticals The ‘Geoffrey Robertson’s Hypotheticals’ approach is finding success in both entertaining and informing the general public of the realisms of forensic science. By invitation from the South Australian Branch of the Australian and New Zealand Forensic Science Society (ANZFSS), I recently led a panel of scientists representing different forensic disciplines and prosecution and defence counsel through a crime scenario. Each panel member explained their role and function in the case and answered hypothetical questions as the case developed. The venue catered for 300 members of the public and was sold out. NIFS is also staging a forensic hypothetical as part of the Australian Science Festival in Canberra on 23 April this year. Early indications are that the 2,500 seat venue will be sold out. This is an excellent forum for demonstrating to the public what the strengths and limitations of forensic science are. It caters for both the strong public interest in forensic science and the need for them to be properly informed. Perhaps in a more sophisticated form, it would also have application for law students and the legal profession in general. The discipline of forensic science has tended toward insularity for too long and there is a genuine need for open, informed discussion and education. It is vital that the legal profession accepts its role in the process. Scientific Advances Each three years, Interpol convenes a meeting on the forensic sciences at which scientific advances in the various disciplines over the three year period are identified and discussed. The most recent meeting was held in Lyon in November 1995 and this paper now summarises the most important advances in technology and forensic science research and development which were reported at that meeting. DNA profiling is still generating a great deal of interest. Internationally, a significant number of laboratories are dispensing with conventional serology methods. The trend is definitely towards polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology with multiplexing of short tandem repeat (STR) systems. This enables profiling at up to six loci with a single sample. The discriminating power is extremely high. There is also an international trend towards the establishment of offender DNA databases. These databases maintain DNA profiles from offenders which will be checked against 4 future crime scene stains. Profiles of biological stains from cases where there is no known offender are also maintained on the database to check for serial offences. NIFS has recently established a working party to investigate the implementation issues of an offender DNA database in Australia. The relatively new technique of capillary electrophoresis (CE) is proving to be valuable in the area of drug profiling. Drug profiling is finding increasing use in the sourcing of drug seizures. The ability of CE to analyse small samples is also proving useful for the detection and identification of explosives. Computer aided identification was seen as a major advance in increasing the objectivity of handwriting examination, particularly in the area of signature analysis. A significant contribution to this area is being made by Mr. Bryan Found and his colleagues working at La Trobe University in Melbourne. Their work is being supported by research grants from NIFS. The use of new lighting and imaging techniques is assisting fingerprint detection and identification. Electrostatic lifting and chemical enhancement is improving the level of shoe print detection. Digital technology is being used to transfer fingerprint and shoe print images from the crime scene to the laboratory. There is still international debate over the set number of points for fingerprint detection. The University of Laussane is conducting research related to the frequency of occurrence of the different fingerprint characteristics. Finally, novel methods of manufacture of drugs such as amphetamines and explosives being circulated on the Internet is necessitating new methods of analysis. SUMMARY Technological advance is an important aspect of ensuring that the best possible scientific evidence is available to the courts. The underpinning of that development has to be appropriate validation and quality management and mechanisms for informing the community of its function, strengths and weaknesses. There are many ‘new leads’ which should be and some which are taking place to strengthen this process. A number of those leads have been identified and discussed in this paper. The success of many of them is reliant on a partnership approach between the key players, the scientific and legal communities. The scientific community is ready...... 5