ProLogis Research Bulletin

Spring 2008

Leonard Sahling

First Vice President

ProLogis Research Group

303-576-2766

lsahling@prologis.com

Based on information compiled by

researchers from Shanghai Jiao Tong

University, Antai College of Economics

and Management.

Inside this Issue…

China’s Special Economic Zones and

National Industrial Parks —

Door Openers to Economic Reform

C

hina launched its “Open Door” reforms in 1978 as a social experiment

— one that was designed to test the efficacy of market-oriented economic

reforms, but to do so within a controlled environment.

Beginning in 1978, China’s central government instituted a series of bold

reforms designed to “open” its economy to direct foreign investment from

abroad in order to improve its citizens’ standard of living.

Not knowing what to expect from economic reform, Chinese authorities

decided not to open the entire economy all at once, but just certain

segments. Hence, Chinese authorities designated four coastal cities as

Special Economic Zones (SEZs) — the precursors of its national industrial

park system.

Several years later, Chinese authorities then created 14 national industrial

parks, officially designated Economic and Technological Development Zones,

or ETDZs. Subsequently, authorities expanded the number of ETDZs to

54, created other kinds of industrial parks, and authorized municipal and

provincial governments to sponsor their own industrial parks.

Foreign enterprises that established operations in these zones

were granted tax breaks, the ability to repatriate profits and capital

investments, duty-free imports of raw materials and intermediate goods

destined to be incorporated into exported products, no export taxes, and a

limited license to sell into the domestic marketplace.

SEZs and ETDZs themselves were given greater political and economic

autonomy. For example, they were also permitted to cut special deals with

foreign enterprises in terms of cheap, or below-market, lease rates for

land or production facilities.

As China’s market-based economic reforms took hold and flourished, SEZs

and ETDZs have come to play lesser roles, and the formal boundaries

previously separating them from the surrounding communities have been

abolished.

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of the Open Door reforms.

China’s current economic miracle is testimony to the efficacy of its

economic reforms and the industrial zones created first to test and then to

propagate those reforms.

Oases of Reform and Modernity.............. 2

China’s “Open Door” Widens................... 2

Economic Performance of the State-Level

Industrial Zones...................................... 3

Policies and Regulations......................... 5

Management Structure of the

Industrial Parks....................................... 8

What’s So Special about National

Industrial Parks?..................................... 9

Other Types of Development Zones.........10

Shanghai — Spearheading Development

in the Yangtze River Delta......................12

Concluding Remarks..............................12

From the Editor......................................15

About ProLogis.......................................16

ProLogis Corporate Headquarters • 4545 Airport Way, Denver, CO 80239 • 303-567-5000 • 800-566-2706 • www.prologis.com

ProLogis Research Bulletin

into Special Economic Zones (SEZs), all of

which were granted special financial, investment, and trade privileges. The two primary

objectives were to attract foreign direct investment into these four zones and to jumpstart an export-led national growth strategy.

These experimental reforms proved to be

immensely successful, and the State Council

subsequently opened up additional cities and

established national industrial parks.

The ETDZs are master-planned industrial parks featuring modern streets, sewer lines, water lines, power plants, and residential housing. Pictured here is the Qinhuangdao ETDZ,

located in Bohai Bay Region in Northeast China.

Oases of Reform and Modernity

Thirty years ago, China was a struggling,

third-world country. Beginning in 1978,

China’s central government instituted a

series of bold reforms designed to “open” its

economy to direct foreign investment from

abroad and improve the standard of living of

its citizens. Its economy has grown nearly

fifteen-fold since then. Today, it is a manufacturing powerhouse, the fourth largest

industrial nation, the third-largest exporter,

and a world-class economic player.

China’s economic transformation has been

based on the classic prescription for growth

— thrift, investment, industriousness, foreign

trade, shifting from agriculture to manufacturing, and a willingness to adopt the best

practices employed by the world’s industrial

leaders. The four Asian “tigers” — South

Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore

— have all used variations of this recipe to

create their own economic successes. The

People’s Republic of China (PRC) has designed and implemented its own export-led

growth strategy, with special emphases on

open cities and industrial parks.

The PRC launched its economic reforms on a

small scale. Its State Council designated four

coastal cities as “open” cities and made them

• www.prologisresearch.com

China’s SEZs and national industrial parks

were oases of reform and modernity. They

occupy large tracts of land; are dedicated to

the export of manufactured products; and

are master-planned with modern streets,

bridges, sewer lines, water lines, power

stations, and residential housing. China’s

national industrial parks are, in effect, small

cities designed to accommodate hundreds

of companies and tens, or even hundreds, of

thousands of their employees.

China’s SEZs and national industrial parks

have also proven to be powerful engines of

growth and deserve much of the credit for

China’s economic transformation.

China’s “Open Door” Widens

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) unveiled

its wide-ranging reforms in 1979 under Mr.

Deng Xiaoping. These bold reforms launched

China’s Open Door Policy.

Having studied the economic successes

of South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and

Singapore, China targeted direct foreign

investment and manufactured exports as the

catalysts for jumpstarting its industrialization

process. Its Open Door Policy offered foreign

companies tax concessions and other incentives to build manufacturing plants that would

be used for exports. The aims were to create

jobs, improve the standard of living, and promote the transfer of technical knowledge.

Not knowing what to expect from economic

reform, Chinese authorities decided to test

the water by opening only certain small

segments of the economy. Hence, the PRC

established Special Economic Zones (SEZs)

— the precursors of its national industrial

parks. These SEZs were patterned after the

ProLogis Research Bulletin

Export Processing Zones that the four Asian

“tigers” had employed so successfully in their

export-led growth strategies.

In 1980, the PRC created four SEZs — one

each in the cities of Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and

Shantou in Guangdong Province; and a

fourth in the city of Xiamen in the neighboring Fujian Province. They were designated as

“Open Coastal Cities” and chosen because

of their proximity to the major world trading

hubs of Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan. Four

years later, the entire province of Hainan was

designated as the fifth SEZ.

China’s controlled experiment with SEZs was

hugely successful, and in 1984 the central

authorities created a variant of SEZs, which

they dubbed Economic and Technological

Development Zones (ETDZs). The difference

between SEZs and ETDZs is one of scale. An

SEZ consists either of a whole city or province

that is granted special financial, investment,

and trade privileges. In contrast, an ETDZ is

situated on a smaller plot of land earmarked

for industry and export-trade development

— but also granted special tax and other privileges. Informally, the ETDZs have come to

known as China’s national industrial parks.

From 1984 until 1988, Chinese authorities

established ETDZs in 14 additional coastal

cities — Dalian, Qinhuangdao, Tianjin, Yantai,

Qingdao, Lianyungang, Nantong, Shanghai,

Ningbo, Fuzhou, Wenzhou, Guangzhou,

Zhangjiang, and Beihei. Shortly afterwards,

the State Council broadened these narrowly

defined ETDZs to encompass much wider

regions, including the Yangtze River Delta,

the Pearl River Delta, the Xiamen-ZhanghouQuanzhou Triangle in south Fujian Province,

the Shandong Peninsula, the Liaodong

Peninsula, Hebei and Guangxi. Together,

these open regions constituted China’s Open

Coastal Belt.

Subsequently, in 1992, the State Council

created another 35 ETDZs. In doing so,

they sought (a) to extend the ETDZs from

the coastline to inland middle and Western

regions and (b) to focus less on fundamental

industries and more on high-tech industries.

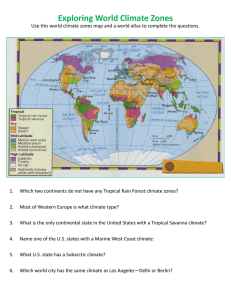

Today, there are 54 state-level ETDZs or

national industrial parks — 14 in the Yangtze

River Delta, nine in the Pearl River Delta,

eight in the Central Region, nine in the Bohai

Bay Region, two in the Northeast Region, and

12 in the Western Region. (See map.)

Economic Performance of the

State-Level Industrial Zones

The PRC launched its “Open Door” economic

reforms in 1978 as a social experiment. It was

designed to test the efficacy of market-oriented economic reforms, but to do so within a

contained, controlled environment. This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of

the Open Door reforms. China’s economic

miracle testifies to the efficacy of those

economic reforms and of the industrial zones

created first to test and then to propagate

these reforms. During the past three decades, China’s merchandise exports have

increased 125-fold and its real gross domestic product (GDP) has grown nearly 15-fold.

(See Exhibits 1 and 2.) In just the last year,

China’s incremental growth in real GDP actually exceeded its entire real GDP in 1979.

These are truly stunning results.

As China’s market-based economic reforms

have taken hold and flourished, the distinct

boundaries that used to separate SEZs and

national ETDZs from their surrounding communities have faded, and so have the starring

roles played by SEZs and national industrial

parks. Nonetheless, the five SEZs and 54

ETDZs still account for substantial shares of

China’s overall economic activity.

•

In 2006, the five SEZs accounted for 5%

of China’s total real GDP, 22% of its total

merchandise exports, and 9% of its total

DFI inflows.

•

At the same time, the 54 national ETDZs

accounted for 5% of total GDP, 15% of

exports, and 22% of total DFI inflows.

Inasmuch as total employment at these five

SEZs and 54 ETDZs represents only about

2.5% of China’s total employment, it is clear

that these economic and industrial zones are

exerting a disproportionately large impact on

China’s overall economy. (See Exhibit 3.)

www.prologisresearch.com • ProLogis Research Bulletin

Exhibit 1: China’s Real GDP, 1978-2006

Constant 2000 Prices and Exchange Rate

1500.0

1300.0

Indexed: 1978=100.0

1100.0

900.0

700.0

500.0

300.0

100.0

78 979 980 981 982 983 984 985 986 987 988 989 990 991 992 993 994 995 996 997 998 999 000 001 02 003 004 005 006

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

2

20 2

19

Source: National Statistics Bureau.

Exhibit 2: China’s Merchandise Exports, 1975-2007

(Billions of U.S. Dollars)

1,400

1,200

Billions of U.S. Dollars

1,000

800

600

400

200

0

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

Sources: China Customs, Haver Analytics, and ProLogis.

• www.prologisresearch.com

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

ProLogis Research Bulletin

Policies and Regulations

When China first cracked its “Open Door” in

1980, it lacked virtually all of the basics (not

to mention amenities) that modern business

enterprises simply take for granted. Absent

were such basics as a transparent legal system, the concept of private property, labor

markets, banks, foreign exchange markets,

and modern infrastructure — including highways, telecommunication facilities, water,

waste management, comfortable living quarters, and energy-supply systems. Only the

most intrepid foreign enterprises were willing

to venture into this uninviting setting.

Members of the State Council knew that

they would have to repair these deficiencies

if they were going to persuade foreign

enterprises to invest in China. Faced with

the enormous challenge of revitalizing the

Chinese economy, authorities settled on

the idea of creating SEZs and ETDZs as

oases of reform and modernity. Various

preferential policies were granted to these

new development zones, including tax

breaks, the ability to repatriate profits and

capital investments, duty-free imports of raw

materials and intermediate goods destined to

be incorporated into exported products, no

export taxes, and a limited license to sell into

the domestic marketplace.1

In addition, SEZs and ETDZs themselves

were given greater political and economic

autonomy. They were permitted, for example,

to develop municipal laws and regulations,

including local tax rates and structures, and

to govern and administer these development

zones. They were also permitted to cut special

deals with foreign enterprises offering cheap,

or “below-market,” lease rates for land or

production facilities.2

Critical to the success of the “Open Door”

policy was the establishment of labor markets within SEZs and ETDZs. Companies

operating inside those zones were allowed to

enter into enforceable labor contracts with

specific term limits, to dismiss unqualified or

under-performing employees, and to adjust wage and compensation rates to reflect

such market forces as worker productivity

and business performance. With the ensuing

The city of Shenzhen is one of the original four SEZs and the “poster child” of China’s

economic transformation. Its current population numbers 8.5 million people, versus

333,000 residents in 1980.

Exhibit 3: Performance Metrics — 2006

Special Economic Zones and National ETDZs

Total Employment*

As % of China Total

Real GDP**

As % of China Total

Utilized FDI***

As % of China Total

Merchandise Exports***

As % of China Total

Total Population*

As % of China Total

Special

Economic Zones

National ETDZs

China

15

4

758

2.0%

0.5%

100.0%

9,101

8,195

183,085

5.0%

4.5%

100.0%

55

130

603

9.1%

21.6%

100.0%

1,686

1,138

7,620

22.1%

14.9%

100.0%

25

---

1,308

1.9%

---

100.0%

* Millions.

** RMB 100 Million.

*** USD 100 Million.

Source: National Statistics Bureau.

meteoric economic success of these development zones came more jobs, higher wages

and compensation rates for those jobs, and

a flood of people from the hinterlands hoping

to land one of the new, higher-paying jobs.

(See Exhibit 4.)

The city of Shenzhen, one of the four original

SEZs, has emerged as an economic powerhouse. In 1980, it was a sleepy backwater with

www.prologisresearch.com • China’s SEZ and NETDZ Economic Zones

LEGEND

NETDZ Economic Zones

Special Economic Zones

Main Logistics Corridor

Economic Zone – Western Region

Economic Zone – Northeast Region

Economic Zone – Baohai Bay Region

Economic Zone – Central Region

Economic Zone – Yangtze River Delta Region

Economic Zone – Pan-Pearl River Delta Region

ProLogis Research Bulletin

Exhibit 4: Performance Metrics — China’s SEZs

1980

Total

2.2

43.2

149

0.2

27.6

11.2

Zhuhai

365

199

0.3

10.7

13.1

2,973

1,336

1.1

4.9

251.0

934

482

0.6

0.0

140.3

Total

Zhuhai

415.6

5,525

2,315

---

0.1

0.0

11,569

5,524

13.5

354.4

1,018.9

882

326

3.9

179.9

563.4

412

254

1.0

52.6

33.4

Shantou

3,274

1,674

2.4

27.7

256.9

Xiamen

1,027

586

1.8

73.3

165.3

Hainan

5,975

2,684

4.3

20.9

0.0

13,648

7,085

44.5

762.8

10,732.8

1,678

1,092

17.2

389.9

8,151.6

641

393

4.1

69.1

488.6

3,698

1,875

7.2

130.8

839.6

781.5

Management Structure of the

Industrial Parks

Each national ETDZ is managed by a management committee, which is an arm of the local

municipal or provincial government. Each ETDZ

also has its own Development Co., Ltd., whose

main task is to attract foreign direct investment — that is, to convince foreign enterprises

to take up residence in its park.

Xiamen

1,119

679

5.7

72.4

Hainan

6,512

3,046

10.2

100.5

471.4

17,632

9,919

190.1

5,121.6

29,551.9

The management committees are responsible for managing the municipal affairs of

their respective industrial parks. Their main

duties include:

• Overseeing the delivery of municipal

services (e.g., police, fire, and garbage

collection) to the resident enterprises.

• Preparing and administering the budgets

and financial statements of their industrial

parks, to maintain the parks’ fiscal health.

4,492

2,985

84.2

1,309.9

20,527.4

•

890

633

18.3

539.3

2,115.3

Administering and managing the parks’

land, infrastructure improvements, planning, and construction permits.

•

Exercising labor administration to protect

the lawful rights and interests of both

workers and employers.

Total

Shenzhen

Zhuhai

Shantou

Total

Shenzhen

Zhuhai

Shantou

4,013

2,052

26.2

895.8

2,600.2

Xiamen

1,214

903

25.1

1,321.6

3,479.2

Hainan

7,024

3,345

36.3

1,055.0

830.0

22,497

11,994

402.5

4,409.8

47,488.0

Shenzhen

Total

7,012

4,750

218.7

1,961.5

34,563.3

Zhuhai

1,237

789

33.1

815.2

3,645.8

Shantou

4,588

2,071

47.7

170.9

2,596.1

Xiamen

2,050

1,038

50.2

1,031.5

5,879.8

Hainan

2006

Exports #

4,481

Shenzhen

2000

Utilized

FDI #

333

Hainan

1995

Real GDP**

10,131

Xiamen

1990

Total

Employment*

Shenzhen

Shantou

1985

Total

Population*

333,000 residents. Today, it has 8.5 million

residents, most of whom have relocated from

other parts of China. Its real GDP has soared

from RMB 200 million in 1980 to more than

RMB 600 billion today — a 300-fold increase.

Total

Shenzhen

7,609

3,346

52.7

430.8

802.9

25,274

14,863

910.1

5,465.7

168,640.0

8,464

6,475

581.4

3,268.5

136,095.6

10,770.7

Zhuhai

1,416

940

63.5

666.1

Shantou

4,954

2,228

74.1

139.6

3,483.0

Xiamen

2,250

1,395

100.7

707.5

17,268.2

Hainan

8,190

3,825

90.5

684.0

1,022.5

* In thousands.

** Billions of constant-RMB.

# Millions of US dollars.

Source: National Statistics Bureau.

• www.prologisresearch.com

The national ETDZs compete not only with

each other to attract new enterprises, but

also with the thousands of provincial and

municipal industrial parks. Hence, each management committee strives to distinguish

its park in terms of its municipal services,

the quality of its infrastructure, and its appearance and “curb appeal.” (See text box

— Provincial and Municipal Industrial Parks.)

In some cases, the industrial parks have

proved to be so successful that they have run

out of space. It then falls to the management

committees to spearhead efforts to expand

the parks. There are clear-cut rules governing

applications for expansion, and the applications must be approved first by the Ministries

of Commerce, Land and Resources, and

Construction and then by the State Council.

ProLogis Research Bulletin

What’s So Special about National

Industrial Parks?

China decided that it wanted to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) as a catalyst for

modernizing its economy. With other countries also competing for these FDI funds,

China needed to do something to distinguish

itself from the rest of the pack.

China’s solution was to create the national

ETDZs — or national industrial parks, as they

have come to be known. Granted, China’s huge

workforce and low wage rates were major

selling points in attracting foreign manufacturers, but Chinese authorities sought to devise

significant additional incentives to bolster their

competitive edge. Hence, foreign companies

were offered a wide array of incentives encouraging them to locate their new facilities in one

of China’s 54 national ETDZs.

First and foremost were their preferential tax

treatments. Foreign enterprises that locate

facilities in an industrial park are eligible for a

number of tax breaks:

•

Foreign enterprises that located within

these zones were subject to a lower

Enterprise Income Tax (EIT) — 0% for the

first two years and then half the normal

33% rate for the next three years.

•

After the first five years, foreign enterprises that export 70% or more of what they

produce are subject to a 15% EIT rate.

•

Foreign enterprises have a five-year net

operating loss carry-forward provision.

•

If a foreign enterprise re-invests the

profits from its China-based operations

either into an existing facility or into

another facility built within an industrial

park, then 40% of the income taxes paid

on the re-invested profits are returned to

the foreign enterprise.

•

Foreign enterprises are exempted from

customs duties and VAT on those imported raw materials, components, and

intermediate products that are used in

manufactured final goods for export.

These tax preferences created two effective

tax rates — 12% for foreign entities versus

25% for domestic companies.

The Suzhou Industrial Park is located in the Yangtze River Delta about 80 kilometers west

of Shanghai. It encompasses nearly 5,000 companies – including 1,800 foreign-owned

– and more than 330,000 workers.

China amended its corporate

tax regime on March 16,

2007, and the new tax regime took effect on January

1, 2008.3 The main purpose

of this new regime is to

introduce neutrality into the

tax system — to level the

playing field — as it applies

to foreign or domestic enterprises. China’s 2007 Tax

Law establishes a common

effective tax rate of 25% for

both foreign and domestic

companies. However, some

of the former tax preferences have been retained, and

the 2007 Tax Law provides

transitional rules.

Provincial and Municipal

Industrial Parks

In addition to the national ETDZs,

various provincial and municipal

governments have also sponsored

industrial parks — thousands of

them, in fact. However, in 2003

several PRC ministries conducted

a nationwide inquiry into rampant

land abuses at these local-level

industrial parks. As a result, more

than 4,700 development zones

were shut down, leaving only about

2,000 in operation (including about

230 national development zones).

Foreign investors are well advised to be cautious about choosing factory locations in provincial

or municipal industrial parks. In

particular, investors should ensure

that a zone’s sponsoring authorities

have appropriate central government permission for all the incentives being offered.

Non-tax incentives are also

commonly used to encourage foreign companies to

locate within specific industrial parks. They include

government-financed hiring

and training programs, government-financed employee

housing, and subsidies or outright gifts of

land for production facilities. (Land in China,

however, is owned by the state. Foreign

www.prologisresearch.com • ProLogis Research Bulletin

entities are permitted only to enter into

long-term leaseholds for land.)

All such non-tax incentives must be negotiated directly between the local governments

and the foreign enterprises. Of course, with

the 54 national ETDZs all competing against

each other (and also competing against a

plethora of provincial and municipal industrial

parks), foreign enterprises often become the

beneficiaries of having multiple options from

which to choose.

Another incentive encouraging foreign enterprises to locate in China’s industrial parks are

the physical layouts of the parks. They have

been built mostly on greenfield development

zones located just outside of major cities and

encompass generally 2,500 to 10,000 acres.

They are usually master-planned sites fitted

out with new infrastructure — new roads, new

bridges new water lines, new sewer lines, and

new electrical plants. Additionally, the central

government has developed an extensive network of high-speed motorways that link the

national ETDZs to local cities, nearby ports,

outlying regions, and other ETDZs.

Foreign enterprises lease building pads within

a given national ETDZ directly from its management committee. The latter also acts as

the company’s agent in securing the necessary construction and operating permits. It is

in the management committee’s best interest

to get new construction projects up and running as quickly as possible.

Other Types of Development Zones

China’s central government has created

several other kinds of economic development

zones besides ETDZs. The two most important ones are free trade zones and export

processing zones.4 Free Trade Zones (FTZs): Chinese authorities established FTZs to promote export trading and bolster China’s role as a major transshipment point for international trade. The

Waigaoqiao FTZ in Shanghai was China’s first

and was established in June 1990. During the

next six years, the State Council approved

another 14 free trade zones throughout

China, all situated at or near major ports.

10 • www.prologisresearch.com

China’s FTZs are focused on bonded services and a few trading functions, including

warehousing, foreign exchange transactions,

marketing, and export processing. No manufacturing is permitted, except for light processing such as packaging or labeling. They

are the only place in China where foreign

companies are allowed to trade and operate

in their own currencies. Hence, all FTZs must

be approved by the State Council.

China’s so-called Free Trade Zones would

more aptly be translated from Chinese as

“Bonded Zones.” These Bonded Zones have

more circumscribed functions than the Free

Trade Zones found elsewhere in the world.

The foremost distinction is that China’s

Bonded Zones are “inside the boundary and

under Custom’s direct supervision,” whereas

FTZs elsewhere are generally outside of

Custom’s direct supervision.

This distinction underpins three major differences between China’s FTZs and those in

other countries. First, China’s Bonded Zones

are supervised and administered directly by

its Customs office, and all inbound and outbound goods must be declared and recorded

with this office. Elsewhere, FTZs lie outside of

Custom’s supervision. Second, bonded products may be stored in China’s Bonded Zones

only for a limited time, normally two to five

years. Elsewhere, no such time limit exists

in FTZs. Third, a company that owns bonded

products in China’s Bonded Zones owes the

appropriate duty to the government, but is

permitted to delay payment until ownership

changes or the bonded products are imported

into China. Elsewhere, companies that own

goods stored in FTZs need not recognize any

such liabilities for duties owed.

Export Processing Zones (EPZs): In April

2000, the State Council created the legal

framework for EPZs and established 15 such

zones, to promote the export of products

manufactured in China. No more than 30% of

goods manufactured in EPZs may be sold into

China’s domestic market.

The State Council has designated these zones

as being “inside the boundary, but outside of

Custom’s direct supervision.” In effect, goods

imported into these zones do not need a

ProLogis Research Bulletin

formal customs declaration. As of today, the

State Council has approved 56 EPZs.

Both EPZs and FTZs provide similar exemptions to customs duties and VAT. First, goods

imported into them are exempt from customs

duties until the goods leave the zones.

Second, VAT is not levied on any activity that

takes place inside the zones. Third, if the

goods are exported to destinations outside of

China, they are exempt from customs duties

and VAT.

However, EPZs and FTZs specify different

exemptions from customs duties and VAT in

two situations. The first occurs when goods

are sold to buyers inside China. All goods imported from EPZs are subject to customs duties and VAT on the full value of the finished

goods, with no distinction between imported

and domestically sourced components. The

second applies to the income tax breaks

available to all companies located in FTZs.

In contrast, companies located in EPZs will

be eligible for those same tax breaks only if

they export more than 70% of their products

outside of China.

The Bottom Line: FTZs are the preferred

locations for companies involved in exporttrading and processing. These zones tend to

attract, for example, foreign-owned trading

operations that use China as a transshipment

point – i.e., buying goods produced in China

or elsewhere and then selling them to buyers outside of China. They are also attractive

locations for third-party logistics providers.

In contrast, EPZs are more advantageous

locations for manufacturing companies that

export most, if not all, of their goods outside

of China. These zones are the preferred location, for example, of manufacturing companies that assemble imported components

from outside of China into finished goods for

sale abroad.

EPZs are treated as “outside of China” in

terms of VAT and customs duties. Hence, in

the case where foreign-owned manufacturers

sell more than 70% of their finished goods

outside of China, the sale of those finished

goods will be treated as a transaction that

occurred outside of China and will thus

Pictured here is the skyline of Shanghai’s west side called Puxi, the oldest and largest

section of the city and the one that hugs the western shore of the Huangpu River.

be exempt from VAT and customs duties.

Similarly, the purchase of any raw materials

or components as inputs into those finished

goods will also be exempt from VAT and customs duties.

EPZs and FTZs also diverge in their exportrebate policies. If a company within an EPZ

buys goods from an enterprise in China,

the seller will receive an export rebate and

the in-zone buyer will not have to pay VAT.

However, companies located in FTZs must

pay VAT upfront on any goods sourced in

China and then apply for an export rebate

only after the goods have been re-exported.

Shanghai — Spearheading Development in the Yangtze River Delta

Shanghai is one of China’s four provinciallevel, self-governed municipalities. The other

three are Beijing, Tianjin, and Chongqing.

On April 18, 1990, the State Council established the Shanghai Pudong New Zone,

often referred to as a Super SEZ, abutting

the eastern bank of the Huangpu River. The

Council’s aim was to transform Shanghai

into a global trade and financial hub, and the

Pudong New Zone was intended to jumpstart

www.prologisresearch.com • 11

ProLogis Research Bulletin

the process. City planners from around the

world were brought in to work with Chinese

planners to design a state-of-the-art global

city for the twenty-first century.

Additionally, the State Council extended special

preferential policies to all foreign enterprises

locating operations in this zone, including some

that have not been granted to the other five

SEZs. For example, in addition to the preferential policies of reducing or eliminating customs

duties and income taxes common to ETDZs,

the state also permits the Pudong New Zone

to allow foreign businesses to open financial

institutions and run tertiary businesses.

Nonetheless, China’s SEZs and ETDZs have

still played an important role in China’s

economic transformation, having served as

incubators for economic growth. As those

economic reforms took root and flourished,

authorities allowed them to fan out to the rest

of China. It is doubtful that foreign enterprises

would have been as willing to venture into

China in the 1980s and ‘90s in the absence of

those oases of reform and modernity. Indeed,

many observers maintain that the SEZs and

ETDZs succeeded in accelerating the pace of

China’s economic revitalization.

Concluding Remarks

Endnotes

China’s economy has undergone a phenomenal transformation in 30 years. When the

“Open Door” economic reforms were first

introduced in 1978, it was a struggling, thirdworld country.

Michael J. Enright, Edith E. Scott, and Ka-mun

Chung, Regional Powerhouse: The Greater Pearl

River Delta and the Rise of China, p. 36, May 2005,

John Wiley & Sons (Asia).

China’s SEZs and ETDZs have been instrumental in persuading foreign companies to

invest in China and thereby nurturing China’s

economic revitalization. Today, 30 years later,

China has evolved into a manufacturing powerhouse, the fourth largest industrial country, and a world-class economic player. Last

year, its merchandise exports totaled US$1.2

trillion, making it the world’s third largest exporter (after Germany and the U.S.). China’s

economic reforms have succeeded far beyond

the reformers’ wildest dreams.

Less developed countries now look admiringly at China’s economic metamorphosis and

wonder what lessons may be learned from its

success. One common question is whether

China could have achieved its economic

transformation without the formal structures

of SEZs and ETDZs. In principle, China surely

could have been equally successful without

them. Its economic success owes more to

the classic prescription for growth — i.e.,

thrift, investment, industriousness, foreign

trade, shifting from agriculture to manufacturing, and a willingness to adopt the best

practices employed by the world’s industrial

leaders — than to SEZs and ETDZs directly.

12 • www.prologisresearch.com

1

Wei Ge, Special Economic Zones and the

Economic Transition in China, World Scientific

Publishing, 1999, p. 53.

2

James C. Morgan, “Effects of China’s New Tax

Laws on U.S. Investment,” Legal Analysis &

Review, Manufacturers Alliance/MAPI, July 2007.

3

The information presented in this section has

been compiled from three sources: an email from

my colleagues in ProLogis’ Shanghai office; an

email from Hong Ye, Senior Manager at Deloitte

Touche Tohmatsu CPA, Ltd., in Shanghai; and the

excellent report by Julie Walton, “Zoning In,” The

China Business Review, September-October 2003.

4

ProLogis Research Bulletin

Appendix: China’s 54 National Economic and Technological Development Zones

Bohai Bay Center

GDP

2006

Registered

Enterprises

Employment

2005

Landmass

(sq km)

NETDZ, Name

City, Province

1

Dalian Dev. Zone

Dalian

Liaoning Province

56.25

6,589

149,700

Petrochemicals, electrical equipment, metalwork, machinery,

foods, garments, and pharmaceuticals.

20.00

2

Shenyang ETDZ

Shenyang,

Liaoning Province

27.60

NA

111,500

Autos and auto accessories, medical chemistry, metal

smelting, textiles, apparel, and bio-engineering.

10.00

3

Qinhuangdao ETDZ

Qinhuangdao,

Hebei Province

11.00

4,565

52,200

Cereal and food processing, auto parts, heavy equipment

mfg., and metalwork

6.90

4

Yantai ETDZ

Yantai,

Shandong Province

39.50

NA

110,900

Machinery, autos, IT, biomedicine, fine chemicals, textiles,

and food processing.

10.00

5

Qingdao ETDZ

Qingdao,

Shandong Province

47.00

622

156,000

Home appliances, petrochemicals, port logistics, shipbuilding, and autos.

12.50

6

Beijing ETDZ

Beijing

36.90

2,170

94,000

IT, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, autos, and equipment

mfg.

39.80

7

Tianjin ETDZ

Tianjin

78.06

(foreign) 4,371

(dom.) 9,892

288,300

Electronic communication, biomedicine, machinery mfg.,

and food and beverage.

33.00

8

Yingkou ETDZ

Yingkou,

Liaoning Province

13.50

NA

144,900

Mineral processing, apparel, food processing, lumber,

and leather processing.

5.60

9

Weihai ETDZ

Weihai,

Shandong Province

10.02

NA

54,544

Autos, machinery, electronics, chemicals, medicine, textiles,

foods, and building materials.

5.72

Total

319.83

Industry Cluster

1,162,044

143.52

Yangtze River Delta

10

Ningbo ETDZ

Ningbo,

Zhejiang Province

27.10

(foreign) 1,058

11

Lianyungang ETDZ

Lianyungang,

Jiangsu Province

8.02

NA

12

Suzhou Industrial Pk.

Suzhou,

Jiangsu Province

67.95

(foreign) 1,800+

(dom.) 3,000+

13

Kunshan ETDZ

Kunshan,

Jiangsu Province

53.90

14

Hangzhou ETDZ

Hangzhou,

Zhejiang Province

15

Wenzhou ETDZ

Wenzhou,

Zhejiang Province

16

Minhang ETDZ

17

147,000

Electronics, machinery, food, chemicals, and textiles

29.60

Pharmaceuticals, new matls., new energy, petrochemicals,

shipbuilding, and food.

3.00

330,900

Electronics, telecom., new materials, precision and mechanical engineering, and biological and pharmaceuticals.

70.00

(foreign) 1,000+

260,000

IT, precision machinery, service trade, biotechnology, and

daily necessities.

10.00

21.20

NA

112,300

Mobile communication, pharmaceuticals, beverages, and

home applicances.

10.00

9.60

NA

92,000

Mech. and electrical equipment, electronic info., pharmaceuticals, building matls., and textiles.

9.11

Shanghai

12.75

NA

33,800

Electronics, pharmaceuticals, medical, and light industry

3.08

Caohejing ETDZ

Shanghai

38.10

1,400+

97,700

IT, new materials, biomedicine, and aerospace equipment.

18

Hongqiao ETDZ

Shanghai

7.47

NA

14,000

Exhibition, displays, office, catering, and shopping

19

Jinqiao Export

Processing Zone

Shanghai

40.22

NA

106,200

Electronic info., autos and auto parts, home appliances,

precision machinery, biomedicine, and refinery chemicals.

27.38

20

Daxie ETDZ

Ningbo,

Zhejiang Province

8.61

NA

16,800

Energy transfer of petrochemical industry, near-port petrochemical and port logistics.

36.00

21

Xiaoshan ETDZ

Hangzhou,

Zhejiang Province

9.98

690+

72,500

Electronic communication, precision machinery, health food,

textiles, and building materials.

22

Nanjing ETDZ

Nanjing,

Jiangsu Province

14.70

(foreign) 400+

32,000

Electronic information, biomedicine, light mfg., and new

materials.

11.37

23

Nantong ETDZ

Nantong,

Jiangsu Province

11.80

(foreign) 600+

35,200

Chemicals, textiles, biomedicine, electronic machinery, and

services.

24.29

Total

331.40

27,100

1,377,500

13.30

0.65

9.20

256.98

www.prologisresearch.com • 13

ProLogis Research Bulletin

Appendix: China’s 54 National Economic and Technological Development Zones

Pearl River Delta

GDP

2006

Registered

Enterprises

Employment

2005

NETDZ, Name

City, Province

24

Guangzhou ETDZ

Guangzhou,

Guangdong Province

78.90

840

132,000

25

Guangzhou Nansha

ETDZ

Guangzhou,

Guangdong Province

20.99

NA

26

Huizhou Dayawan

ETDZ

Huizhou,

Guangdong Province

10.02

27

Yangpu ETDZ

Hainan Province

28

Zhangjiang ETDZ

29

Industry Cluster

Landmass

(sq km)

Raw chemical mfg., chemicals, electrical machinery and

equipment, communications equip., smelting and processing

of nonferrous metals, and foods and beverages.

38.57

67,400

Plastics, processed food, electronic equipment, chemicals,

and ships.

27.60

NA

76,000

Electronic equipment, paper, steel, and petro-chemicals.

4.39

NA

20,000

Extraction of oil and natural gas, paper and paper products.

Zhangjiang,

Guangdong Province

50.50

638

35,000

Special paper products, electronic equipment, information

equipment, bio-medical, and sea products

Haicang Investment

Zone

Xiamen,

Fujian Province

18.09

(foreign) 178

127,800

Chemicals, machinery, electronics, polyester, PVC products,

photo-sensitive materials, and electric power.

100.00

30

Dongshan ETDZ

Dongshan,

Fujian Province

1.36

NA

20,000

Electronics, processed food, light industry, and new materials.

10.00

31

Fuqing Rongqiao

ETDZ

Fuqing,

Fujian Province

10.90

458 (in 2005)

45,000

Electronics and automobile glass.

10.00

32

Fuzhou ETDZ

Fuzhou,

Fujian Province

13.50

1,000+ (foreign)

85,000

Electronics, photoelectric machinery, biochemical pharmaceuticals, building materials, metallurgy, and textiles.

10.00

Total

208.65

608,200

9.98

30.00

9.20

245.35

Central Region

33

Changsha ETDZ

Changsha,

Hunan Province

15.30

NA

35,900

Advanced machines, electronic information equipment,

construction materials.

12.00

34

Wuhan ETDZ

Wuhan,

Hubei Province

21.50

1,427 (2002)

81,000

Cars, car parts, processed foods and beverages, medicines,

and biological engineering.

10.00

35

Nanchang ETDZ

Nanchang,

Jiangxi Province

16.17

368

83,200

Electric applicances, air conditioners, largest IC mfg., cars,

papermaking.

9.80

36

Hefei ETDZ

Hefei,

Anhui Province

18.60

NA

42,500

Cars, engineering machinery, electronic equipment, and

processed foods.

18.60

37

Wuhu ETDZ

Wuhu,

Anhui Province

13.40

NA

51,000

Construction materials, cars, car parts, and electronics.

10.00

38

Huhhot ETDZ

Huhhot,

Inner Mongolia

6.89

NA

23,600

Dairy products, biological medicines, organic foods, machinery, and textiles.

9.80

39

Zhengzhou ETDZ

Zhengzhou,

Henan Province

4.90

NA

40,000

Information technology, food processing, printing and packaging, electric power equipment.

12.49

40

Taiyuan ETDZ

Taiyuan,

Shanxi Province

2.04

NA

23,500

Electronics, biological medicines, food processing, and hightech planting.

9.60

Total

98.80

380,700

92.29

Northeast Region

41

Changchun ETDZ

Changchun,

27.65

1,540

111,400

42

Harbin ETDZ

Harbin,

13.60

NA

64,500

Total

14 • www.prologisresearch.com

41.25

175,900

Car parts, grain processing, biological medicines, and construction materials.

10.00

Car parts, medicines, foods, and textiles.

10.00

20.00

ProLogis Research Bulletin

Appendix: China’s 54 National Economic and Technological Development Zones

Western Region

GDP

2006

Registered

Enterprises

Employment

2005

Landmass

(sq km)

NETDZ, Name

City, Province

43

Chengdu ETDZ

Chengdu,

Sichuan Province

8.78

NA

58,400

Cars, machinery, new materials, medicines, steel, and

organic foods.

9.94

44

Kunming ETDZ

Kunming,

Yunnan Province

4.18

NA

27,300

Tobacco products, information and electronic equipment,

food processing, biological medicines, and new materials.

9.80

45

Guiyang ETDZ

Guiyang,

Guizhou Province

2.82

93,100

Engineering equipment, power machinery, airplane parts,

and car parts.

9.55

46

Nanning ETDZ

Nanning, Guangxi

Autonomous Region

4.16

232

42,300

Electronics, fine chemicals, cars, car parts, papers, and

medical equipment.

47

Chongqing ETDZ

Chongqing,

11.10

1,225 (2001)

86,300

Information technology, biological medicine, cars, fine

chemicals, new materials, textiles, and organic foods.

9.60

48

Xi’an ETDZ

Xi’an,

Shanxi Province

14.20

1,800 (2005)

45,200

Electronic machinery, light industrial products, biological

medicine, and new materials.

9.88

49

Yinchuan ETDZ

Yinchuan, Ningxia

Autonomous Region

3.26

225

17,400

Digital control machinery, heavy steel casing, precision

processing, wind power, equipment, power distribution

equipment, crane facilities, and electric instruments.

7.50

50

Xi’ning ETDZ

Xi’ning,

Qinghai Province

1.66

NA

26,000

NA

4.40

51

Lanzhou ETDZ

Lanzhou,

Gansu Province

2.08

471

28,100

Mining, Non-ferrous metal ore processing,

petroleum machinery, and electronics.

9.53

52

Tibet Lhasa ETDZ

Lhasa,

Tibet

0.98

NA

NA

NA

2.51

53

Urumqi ETDZ

Urumqi, Xinjiang

Autonomous Region

3.24

NA

15,500

Furniture, electronic equipment, and

alcoholic beverages.

4.30

54

Shihezi ETDZ

Shihezi, Xinjiang

Autonomous Region

2.71

NA

26,000

Textiles, organic foods, and modern

agricultural equipment.

11.20

Total

Grand Totals

Industry Cluster

10.80

59.17

465,600

99.01

1,059.10

4,169,944

857.15

Source: China Development Zone Yearbook.

From the Editor…

I recently traveled to China on business and visited several industrial parks. They were totally

different from any others that I had seen elsewhere. For example, a large American industrial

park might include as many as 15 to 20 industrial buildings and encompass as many as 2,500 to

7,500 workers. In contrast, China’s industrial parks are more like small cities, often encompassing

thousands of acres and hundreds of thousands of workers.

Leonard Sahling

First Vice President

ProLogis Research Group

303-567-5766

lsahling@prologis.com

I left China intrigued by its industrial “city-parks.” This report is the result of my efforts to

understand better what role they play today in China’s economy and what role they have played in

facilitating China’s economic transformation. Theirs is a fascinating story, and it could not have told without the help of researchers at Shanghai

Jiao Tong University. They did a brilliant job of digging up the facts. We worked together in assembling them into this story highlighting just how

critical these zones have been in fostering China’s amazing economic metamorphosis.

www.prologisresearch.com • 15

ProLogis Research Bulletin

About ProLogis

ProLogis is the world’s largest owner, manager, and developer of distribution facilities, with operations in 121

markets across North America, Europe, and Asia. The company has $38.8 billion of assets owned, managed,

and under development, comprising 526 million square feet (49 million square meters) in 2,817 properties as

of March 31, 2008. ProLogis’ customers include manufacturers, retailers, transportation companies, third-party

logistics providers and other enterprises with large-scale distribution needs. Headquartered in Denver, Colorado,

ProLogis employs over 1,500 people worldwide.

ProLogis Research Reports

Additional ProLogis research reports are available to download from the ProLogis Research Center. Go to www.prologisresearch.com to view our full library of research reports.

© Copyright 2008 ProLogis. All rights reserved.

This information should not be construed as an offer to sell or the

solicitation of an offer to buy any security of ProLogis. We are not

soliciting any action based on this material. It is for the general

information of ProLogis’ customers and investors.

This report is based, in part, on public information that we consider

reliable, but we do not represent that it is accurate or complete, and

it should not be relied on as such. No representation is given with

respect to the accuracy or completeness of the information herein.

Opinions expressed are our current opinions as of the date appearing

on this report only. ProLogis disclaims any and all liability relating

to this report, including, without limitation, any express or implied

representations or warranties for statements or errors contained in, or omissions from, this report.

Any estimates, projections or predictions given in this report are

intended to be forward-looking statements. Although we believe that

the expectations in such forward-looking statements are reasonable,

we can give no assurance that any forward-looking statements will

prove to be correct. Such estimates are subject to actual known and

unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors that could cause actual

results to differ materially from those projected. These forwardlooking statements speak only as of the date of this report. We

expressly disclaim any obligation or undertaking to update or revise

any forward-looking statement contained herein to reflect any change

in our expectations or any change in circumstances upon which such

statement is based.

No part of this material may be (i) copied, photocopied, or duplicated

in any form by any means or (ii) redistributed without the prior written

consent of ProLogis.

0508

ProLogis Corporate Headquarters • 4545 Airport Way, Denver, CO 80239 • 303.567.5000 • 800.566.2706 • www.prologis.com