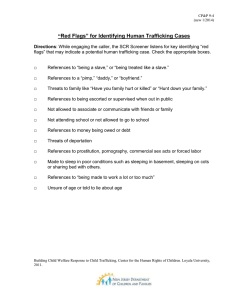

Human Rights and Human Trafficking

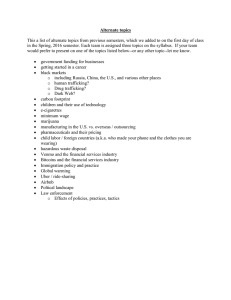

advertisement