The Role of ESL Teacher Support in Facilitating School Adjustment

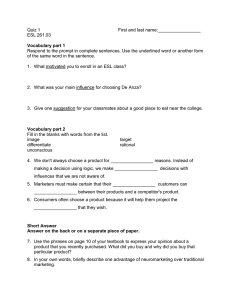

advertisement