Teaching and Learning Online

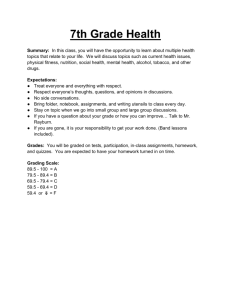

advertisement