The Nine No-No`s Meet the Nineties - Berkeley-Haas

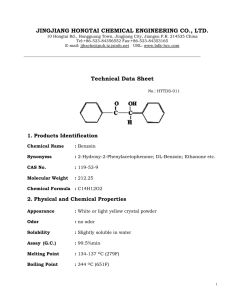

advertisement