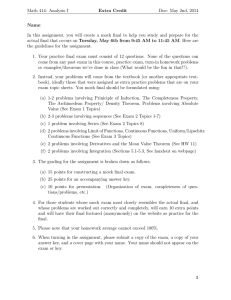

children`s rights count

advertisement