The FA Chairman`s England Commission

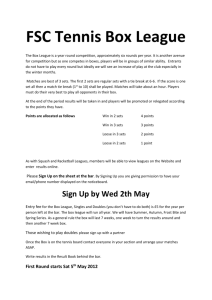

advertisement