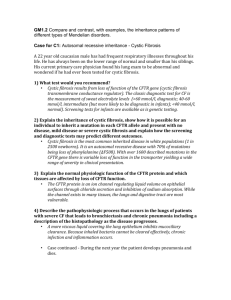

Mechanisms of CFTR Functional Variants That Impair Regulated

advertisement