How Leaders Support Teachers to Facilitate Self

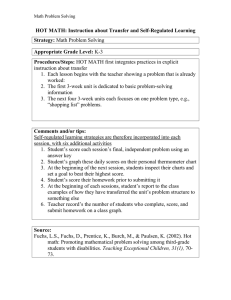

advertisement