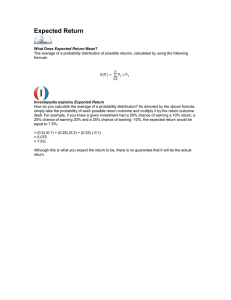

No more NEETs

advertisement