Developing Shared-Use Food and Agricultural Facilities in North

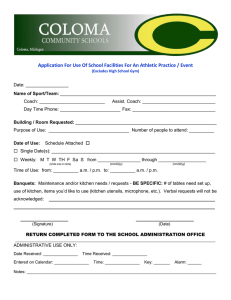

advertisement