CONCRETE PAVINGTechnology - Minnesota Department of

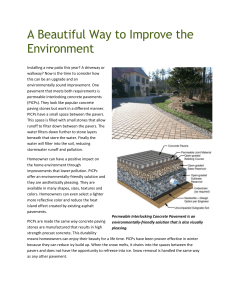

advertisement