The Consulting Engineer in

the 21st Century

Presented by:

1.

David C Russell

Summary

This paper looks at the challenging, and changing, role of

the consulting engineer in the 21st century. It looks at past

experiences and how to use consulting engineers in a highly

competitive world. The perspective is from both sides of the

industry, from that of the operating companies looking to

implement a project which requires specialised knowledge, to

the consulting engineers themselves, seeking to match their

expertise with the operating companies expectations.

Examples are given of how the resources bank of an engineering

consultancy can be used to improve and enhance the outcome of

pulp and paper company projects.

Consulting engineers also work for vendor and equipment supply

companies, both in the provision of engineering services and in

interfacing between different processing units.

The role of the consulting engineer is indeed a challenge in the

21st century, but by following a few simple guidelines, operating

companies, vendors and consultants can achieve a mutually

satisfying outcome at the end of the day.

2. Introduction

Until about 15-20 years ago, it was common for the pulp

and paper companies to have their own project engineering

departments. Some still do, but for the most part the large

engineering departments have shrunk to mere skeletons of

their former selves. For example, in the mid 1980’s Carter Holt

Harvey, Kinleith, had the largest projects engineering department

outside the public sector. The emphasis on core business and the

competitive nature of the pulp and paper business required a

different approach.

© Copyright Beca 2010, all rights reserved unless expressly agreed.

Senior Project Manager, Beca

Traditionally the preserve of civil and structural engineers,

the consulting engineering business has expanded to include

engineers of all disciplines. Initially a number of these came from

the pulp and paper companies themselves, with project and

operating backgrounds, but latterly the consultant companies are

supplementing their basic strengths with graduate engineers and

engineers from other industries and backgrounds. The consulting

engineering companies have become repositories or banks of

skills which are available for use by the pulp and paper operating

companies.

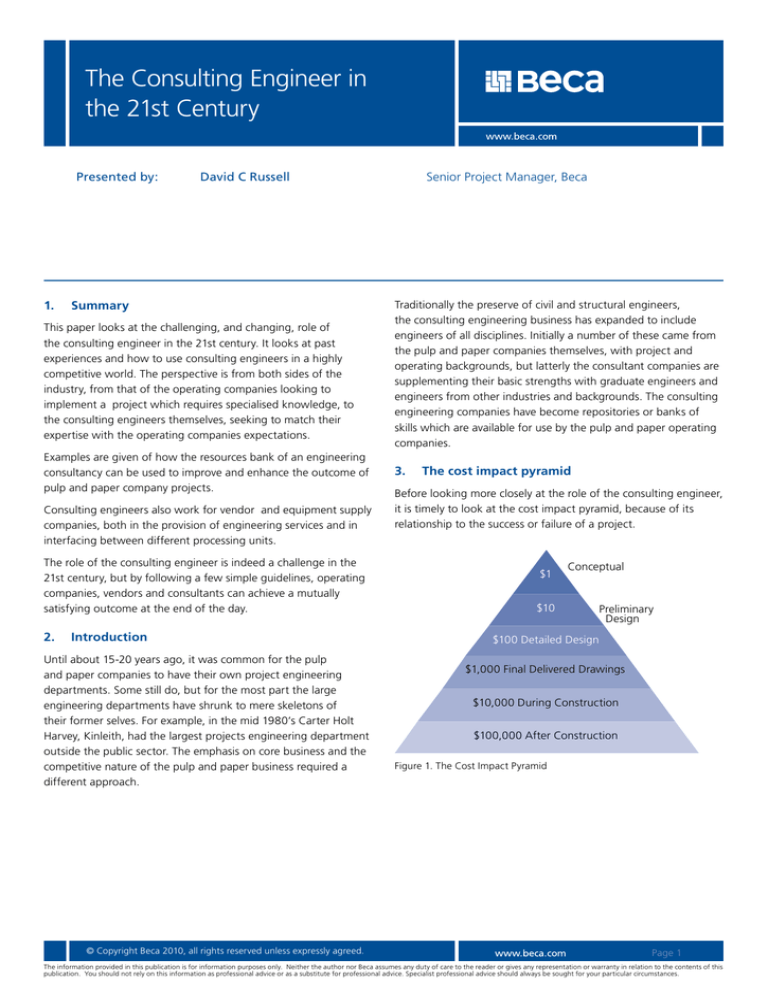

3.

The cost impact pyramid

Before looking more closely at the role of the consulting engineer,

it is timely to look at the cost impact pyramid, because of its

relationship to the success or failure of a project.

$1

Conceptual

$10

Preliminary

Design

$100 Detailed Design

$1,000 Final Delivered Drawings

$10,000 During Construction

$100,000 After Construction

Figure 1. The Cost Impact Pyramid

Page 1

The information provided in this publication is for information purposes only. Neither the author nor Beca assumes any duty of care to the reader or gives any representation or warranty in relation to the contents of this

publication. You should not rely on this information as professional advice or as a substitute for professional advice. Specialist professional advice should always be sought for your particular circumstances.

1.1 The Consulting Engineer in the 21st Century

The point of the cost impact pyramid is that good engineering

in the first phases of the project has a very substantial effect on

the later costs, particularly as the project moves towards start up.

The message is clear but not always recognised: money spent up

front is well repaid in the later stages of the project. Whilst hard

data is not easy to come by, anecdotal evidence suggests that the

return from good engineering in the front end of the project has

a yield of the order of ten fold in capital cost. That is, spending

an extra dollar on engineering at the front will save around $10

on capital.

4. The parties

We can define the main parties as these:

The consulting engineering company which sells expertise

and knowledge, supplementing that resident within the

operating and/or equipment supply companies;

The vendor or equipment supply company, which can supply

engineering services in addition to equipment, but may

also require the consulting engineering company’s service

to supplement its own, and/or to engineer the interfaces

between their units and the services required for these units;

The operating company, with a specific need, either on-going

or one-off, for project or maintenance engineering which it

cannot meet from its own resources.

The problem is therefore one of matching needs to resources.

We can now look in more detail at the nature of each player.

4.1 The operating company

An operating or manufacturing company derives its income from

the production of a product, for which there is a market. If both

product and market exist in an environment which generates

acceptable returns, the company generates sufficient income to

pay its staff, meet its bills, and generate a return to shareholders.

Company effort is directed towards production and marketing.

Engineering services are largely, although not exclusively, directed

towards solving problems in the process which are impeding

production and which by definition are short term in nature. The

emphasis remains, and will remain, on producing product at the

appropriate cost and quality.

4.2 The vendor

The main purpose of the vendor or equipment supply company

is to sell equipment. This may be specialised equipment, for

example digesters, screens, washing units, as well as complete

systems such as pulp dryers or paper machines.

The vendor company may offer engineering as well as

equipment. Within the industry, views differ on whether the

supply of engineering services is part of the vendor company’s

core business. Some vendor companies have moved away from

the engineering services area altogether whilst other companies

have sub-contracted the supply of engineering services.

Regardless of the approach, in times of high demand the vendor

company may look to the engineering consulting company to

supplement its own resources, in a similar manner to that of the

operating company.

Vendor engineering is a valuable asset when used appropriately,

and that is when the design of components such as piping

systems is integrally connected and in close proximity to the

process equipment. However, two cautions should be noted

when operating companies start to consider whether vendor

engineering is suitable for their project:

1. Vendor engineering applies only to the package of work for

which that vendor is responsible. If the operating company

has “cherry picked” – selected what it considers the best

packages available from different vendors – then someone,

typically a consulting engineer, is required to connect the

various packages together in such a way as to achieve the

aims of the project.

2. Vendor engineering can be offered on a reduced fee or even

a no-fee basis. However, costs always appear in one form or

another, so operating companies should examine where the

engineering costs are located.

4.3 The consulting engineering company

The consulting engineering company has no “manufactured”

product in the normally accepted sense. Instead, it relies on

commissioned work to generate its income and to pay its

employees.

The two “products” which the consulting engineering company

markets are time and expertise.

Both “products” are related to resources. Time is related

through the availability of people to carry out the necessary

work. Expertise is available through the experience which the

consultant has acquired when working on different projects for

a range of operating companies, and from the additional skills

which are usually available from international ownership and/or

affiliation.

The use of its services is a direct result of the requirements of the

operating company and to a lesser extent, the vendor company.

An analysis of pulp and paper project activity shows this to be

cyclical: periods of high activity interspersed with periods of

relatively quiescent activity. For example, an analysis of activity

at the Kinleith mill complex over the last 15 years shows this

pattern, with the following peaks:

1985-86: Recovery boiler and evaporator installation.

1989-90:

Bleach plant revamp; new oxygen delignification;

screening and washing upgrade.

1996-98:

Paper machine modernisation

Page 2

1.1 The Consulting Engineer in the 21st Century

Obviously, a consultant engineering company, which relies on

major project work from one operating company, will have a lean

time indeed.

In order to survive during periods of low activity, a consultant

company needs a minimum of two clients, neither of whom are

carrying out major project work at the same time. Preferably,

the consultant company will also have client companies which

operate in different industries.

In addition, the consulting engineering company has available

to it a number of systems and procedures which provide a

disciplined approach to conducting a project, regardless of size.

These systems cover areas such as:

Quality systems, such as certification to ISO 9001.

Verification and Validation Procedures

Documentation Production and Control

Job management and contract administration

Risk Management

The implementation of these systems lends a degree of assurance

to the operating company that the conduct of its project is

proceeding in a disciplined and well-ordered manner.

A casual or informal request suggests that the work content, or

scope, is not well known or defined. In this case it is imperative

that the consultant responds to the request with an outline of

the scope, as he understands it, in order to confirm the operating

company’s request. At the very least, this provides an opportunity

to minimise misunderstanding at the outset of the project, when

the consultant has one expectation and the operating company

may have another, and different, expectation.

5.2 The invitation

The invitation to bid typically comes in the form of documents

from the operating company inviting the consultant to make a

proposal. Again the scope of work to be covered is critical and

it is not uncommon for the consultant to assist the operating

company in preparing the invitation to bid.

If the project is still in its initial stages, the consultant will respond

with a proposal for a pre-feasibility or feasibility study. The

proposal outlines the work to be covered, the resources to be

employed, the conditions of contract and the accuracy of the

cost estimate.

In the next section, we outline these in more detail for a typical

project.

The consulting engineering company needs to replenish its

“human capital” from time to time, through losses from natural

attrition, and retirements. What attracts graduates to join an

engineering consultancy? The answer is straightforward: a high

level of job satisfaction. Moving from one project to another,

each with its own particular challenges, provides the opportunity

to increase skills, knowledge and expertise, combined with an

always present challenge.

6.

5.

Typically projects proceed through a number of stages, each

with a different range of accuracy in the scope and estimate.

For example, the following criteria could be used for project

implementation and execution, as summarised in Table 1:

The relationships

The discussion above pre-supposes that a relationship exists

between the two parties. In order to develop the relationship, a

desire for closer contact must exist on both sides.

The process can begin in a number of ways, for example:

5.1 The informal approach

If the consultant is well known to the operating company, the

consultant may have advance notice of proposed new projects.

The process may begin on an informal basis from the operating

company’s perspective, such as a casual request to look into the

feasibility of a project.

However, “casual request” is not a term in the consultant’s

vocabulary, because of the constraints on the consultant’s

method of operation. The consultant has to respond formally

because it has to operate on the basis of a contract, both from

a quality and procedural point of view as well as from a liability

point of view.

Outlining the costs

In preparing a proposal, the consultant looks at both the cost

of the project, in terms of equipment, and the cost of services.

At the same time the consulting engineer is confirming its

understanding of the project requirements with the client, which

may be either the operating company or the vendor company.

6.1 Stages of the estimate

Table 1. Phases and Range of Accuracy

Project Phase

Range of Accuracy

Conceptual

+ 50%

Approval in Principle

+ 25%

Execution

+10%

The level of accuracy is determined by the needs of the operating

company

For example, a project which is but one of a number is unlikely

to require or justify the expenditure necessary for a + 10% order

of accuracy. Instead, an order of accuracy around the 20-30%

mark is sufficient to indicate whether the project has sufficient

economic health to advance to the next stage.

Page 3

1.1 The Consulting Engineer in the 21st Century

Note that the order of accuracy is a plus/minus figure. It is not

always recognised that even a firm and fixed quotation could

be + 10% on the price – through items not included in the

quote (for example, freight/insurance, spare parts and possibly

exchange rate variations). Operating companies have a tendency

to assume that a plus/minus 10% quote is in fact a plus zero %

minus 10% quote but this is not the case. Even at this level the

numbers can be significant: on a $100 million project, 10% is

$10 million, not an insignificant amount.

Similar comments apply to the other order of accuracy estimates.

6.2 Resources

We have already seen that the consultant supplies resources

to complement those of the operating company, when the

workload requires this.

We can see through Figure 2 that the normal resource

requirement for a project is in a bell shaped curve, with the

requirements rising rapidly as the project gets underway,

followed by a peak, then a fall as the project is taken over by the

operating company’s production staff.

Consultant

Resources

7.

Ongoing relationships

The stage is now set for a fruitful and harmonious relationship,

but there are still some requirements which must be met from

the parties:

7.1 Corporate commitment:

Corporate commitment is required on both sides. If the operating

company abrogates its corporate commitment and employs a

“hands off “ type approach, the scene is being set for a poor,

and potentially disastrous, outcome. The operating company

must understand that it cannot pass its responsibilities over to a

consultant company without losing a large measure of control.

It is importance of the operating company having available a

team, with the necessary skills, to manage the consultant. The

maintenance of the consultant/operating company interface,

with a clear view of the objective, is a driving force in the success

or failure of the project.

7.2 Risk Management

One of the tensions which frequently develops on a project is the

assignment of risk. Risk in this context is defined as the risk that

the project will not generate the desired outcome and can be

broken into three major categories:

Resources

7.3 Process risk

Company

Resources

Time

The process risk covers the possibility that the process selected

for the project is inappropriate or only partly successful.

The operating company may wish to assign this process risk

to the consultant or to the equipment vendor. Whilst this may

appear attractive on the surface to the operating company, it

becomes less attractive when examined in detail:

The consultant and vendor companies will inevitably limit the

Figure 2. Resource Requirements

The span over which the resources are supplemented by the

consultant varies with the nature of the project, as does the

number of resources supplied. For example, on a recent major

pulp and paper mill upgrade, the resource requirement spanned

over an 18 month period and peaked at 160 supplementary staff

supplied by the consultant.

degree to which they are exposed to risk.

Insurance companies will not generally insure against process

risk.

More importantly, the party most at risk is not the consultant

or even the vendor, but the operating company, because

it has a much greater financial outlay than any other party.

A number of operating companies now accept that the

transference of process risk to another party is largely

impossible.

Page 4

1.1 The Consulting Engineer in the 21st Century

7.4 Schedule risk

Schedule risk - the risk of the project running beyond the agreed

date - would appear to be an area where the operating company

is largely responsible, but again a more detailed examination

reveals that both parties have obligations in this area.

The parties must agree on the project scope of work. If the

operating company changes its mind on the scope of the work,

a claim for the additional impact may be raised. This impact was

earlier illustrated in the Cost Impact Pyramid (Figure 1).

2. Unforeseen delays, usually equipment delays, which did

not come to light in the earlier and less detailed phase of

the project. Whilst the schedule will normally have some

float available, the operating company will wish to reduce

the float to the minimum and this may later impact on the

schedule.

3. Shutdown schedules, which impact on the time which is

available for installing the equipment for the project. This

applies to the situation when a project is implemented in an

existing mill.

The operating company must respond to requests for

information in a timely fashion. Whilst it is relatively common

for contracts to have “turnaround” clauses, these require a

reasonable degree of discipline for both parties. Again, if the

turnaround periods are not observed, the schedule can slip.

Information from the vendor company is also an area where

the timely flow of information contributes to the project’s

success.

Timely decision making by the operating company. For

example, it would be normal for the consultant to obtain

quotes on equipment and put these forward to the operating

company with a recommendation. Normally an allowance is

made in the schedule for the operating company to consider

the recommendation and authorise negotiations to proceed

with the preferred vendor. Any delays, either through lack of

resources or because the operating company wants different

avenues pursued, will impact on the schedule. The solution is

to have an agreed list of vendors at the outset, together with

an agreed timetable for decision making.

Agreement on the schedule. Typically the operating company

will have a target completion date, within which the

consultant prepares a schedule of the necessary activities.

After agreement on the schedule, it is common for one of

three processes to take place:

1. The operating company delays the start date but maintains

the end date. This places the consultant in an awkward

situation: it must either increase resources (although these

may not be available) and incur additional costs, or inform

the operating company that the schedule can no longer

be met.

7.5 Budget risk

The risk of over-spending the budget depends largely on two

factors: the schedule, discussed above, and the quality of

estimating, covered in Section 8 (i). In all respects, the cost

estimate must be realistic even if this means that the project is

revaluated on its economic justification. All engineers tend to be

optimists, and occasionally budgets reflect this optimism.

The role of the consultant is to prepare a realistic budget, which

is generally higher than the operating company’s first estimate.

The consultant knows, through experience, of the many

unaccounted-for items which could crop up in the project.

In turn, the operating company needs to be quite clear on why

it is carrying out the project, and to identify the go/no go point.

Most consultants, and probably most operating companies,

know of projects where enthusiasm over-ruled good sense, and

a project proceeded which in retrospect failed to produce the

required return on investment because the costs escalated to a

higher than expected point.

For example, a project which starts with a budget of $100 million

is considered, on the normal grounds of project assessment, to

give an acceptable return on funds employed. If this budget has

been unduly optimistic, and the real figure is $150 million, a point

may have been reached where the market cannot accommodate

the extra cost associated with production.

For any project, the consultant can assist in the management

of the project budget, with a range of tools . One of the basic

tools is a cost curve. This curve measures the actual expenditure

against the forecast expenditure, and an example for an actual

project is given in Figure 3:

Page 5

1.1 The Consulting Engineer in the 21st Century

With the realisation that a closer relationship between operating

company and consultant usually works better than a distant

relationship, EPC contract arrangements should be entered into

with considerable forethought and recognition of the inherent

risks.

8.2 Liability

Figure 3. Project Cumulative Cost Curve

This curve flags up significant departures from the planned

budget at an early stage. A lower expenditure than forecast

in the budget may indicate a schedule problem; a higher

expenditure than forecast may indicate an optimistic budget.

Such curves are applicable to both large and small projects.

8. Structural considerations

The operating, vendor and consulting companies have decisions

to make on the structure of their project, and in these the

consultant also has a role.

8.1 EPC or EPCM

Liability covers the area of who pays when the project does not

perform as expected. As already discussed, it is difficult, if not

impossible, for the operating company to pass its process risk to

the consultant. As well, open liability would not be acceptable to

a consultant.

Most standard forms of contract limit consultant liability to set

sums. For example, the IPENZ Conditions of Engagement (Short

Form – Commercial) limits consultant liability to the greater of

five times the value of the fees or NZ$100,000. The conditions of

engagement also require that the consultant carries professional

indemnity insurance for the value of the contract liability.

9.

Rules and results

Finally, what is the 21st century formula for a productive and

mutually satisfying relationship between operating, vendor and

consulting engineering companies? The following are general

points which should lead to an harmonious understanding

between all parties:

Two major structural forms of project structure exist: EPC

(Engineer, Procure, Construct) and EPCM (Engineer, Procure,

Construction Management). The essential differences between

these two forms are:

A common goal for the outcome of the project and what it is

EPC: Fixed price, little or no operating company involvement. The

owner shifts costs, schedule and process risks to the contractor.

A defined scope of work agreed to by all parties.

EPCM: Work up to a target manhour/cost budget, higher

operating company involvement.

A plan which outlines the resources required and available,

The price of an EPC type project arrangement is almost always

higher than an EPCM arrangement, because the risk carried by

the consultant is higher. Furthermore, EPC type contracts are a

“hands off” type of approach from both parties.

designed to achieve.

Clear lines of communication and a willingness to share

information.

A defined budget and schedule for controlling the project.

and matches need with demand.

Other more project specific criteria could be added, but when the

project concludes, all parties want to be able to state:

The project worked, and it was achieved on schedule and within

budget.

Page 6