Addressing IEDs

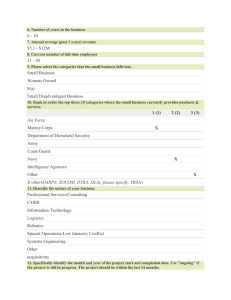

advertisement