Metro Manila, Philippines

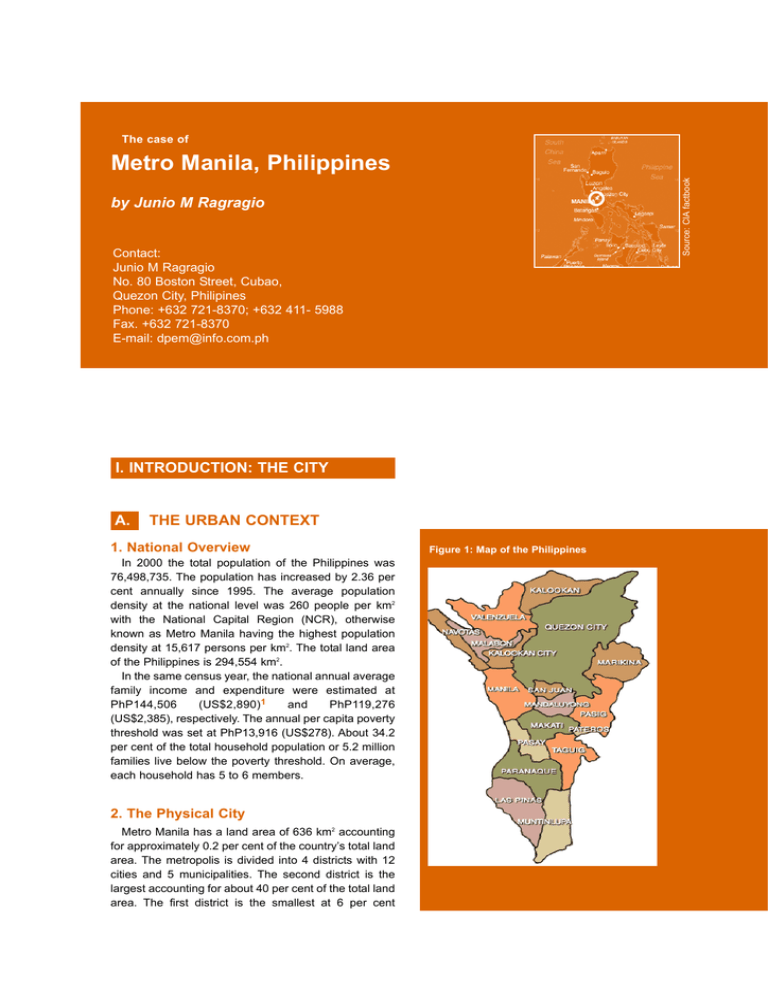

advertisement